Why do most American churches ignore the annual event which began in 1908? Perhaps it is because it is co-sponsored by the World Council of Churches. The vast majority of U.S.churches shun having anything to do with the WCC – and have for decades.

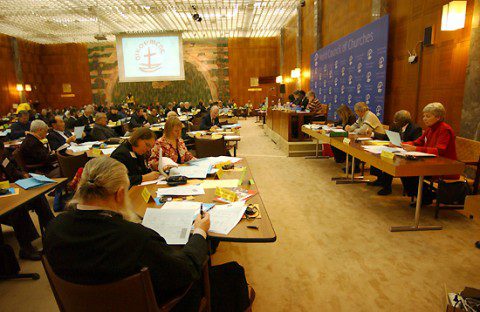

Participants from last year's event

It’s always a real shame when a great idea is shrugged off – particularly since the Week of Prayer isn’t “owned” by the WCC. This year’s official text was approved jointly by the Faith and Order Commission World Council of Churches in Geneva, Switzerland, and the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity in Rome.

But it’s as if your family’s black sheep, Aunt Libby, announces she’s going to celebrate your grandparents’ 48th wedding anniversary with a grand gala. Your mom rolls her eyes and says she’ll take them out to dinner the night before, but will skip Libby’s party since she really needs to stay home to shampoo the rug.

The World Week of Prayer actually was founded by two English clergymen, one Catholic, one Church of England. It gained popularity in the 1930s when it was promoted by a French Catholic layman.

This year, participants are “invited to enter more deeply into our faith that we will all be changed through the victory of our Lord Jesus Christ. The biblical readings, commentaries, prayers and questions for reflection, all explore different aspects of what this means for the lives of Christians and their unity with one another, in and for today’s world.”

For eight days, participants are invited to consider chosen scriptures and a daily theme, which include:

Day One: Changed by the Servant Christ

Day Two: Changed through patient waiting for the Lord

Day Three: Changed by the Suffering Servant

Day Four: Changed by the Lord’s Victory over Evil

Day Five: Changed by the peace of the Risen Lord

Day Six: Changed by God’s Steadfast Love

Day Seven: Changed by the Good Shepherd

Day Eight: United in the Reign of Christ

Participants consider tenets of faith shared by all Christians, such as: “Christ’s victory enables us to look into the future with hope. This victory overcomes all that keeps us from sharing fullness of life with him and with each other. Christians know that unity among us is above all a gift of God. It is a share in Christ’s glorious victory over all that divides.”

So, there no little irony in that the World Council of Churches’ involvement seems to make the event of little interest to most of America’s largest churches.

WCC membership includes almost no conservative Evangelicals. The WCC’s U.S. organization, the National Council of Churches, is dominated byAmerica’s five top liberal and declining denominations: The Episcopal Church in the United States of America, the Presbyterian Church U.S.A., the Disciples of Christ, the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America, the United Church of Christ (Congregationalists) and the United Methodist Church. The Episcopalians alone have lost 1 million members since 1975. The Disciples had 2 million members in 1958 and now are less than half of that.

The Catholic Church declines to join the World Council of Churches. The Southern Baptists are particularly blunt in their assessment:

“The World Council of Churches has long been a boutique of paganism in Christian garb,” writes Russell D. Moore, senior vice president for academic administration and dean of the school of theology at Southern Baptist Theological Seminary in Louisville,Ky. “Believers across the world, whatever their denomination or communion, recognize the spirit of the World Council for what it is: the spirit of antichrist.”

Southern Baptist spokesman Russell D. Moore

One of the great leaders of the Pentecostal/ Charismatic movement, South African author David du Plessis, was disfellowshiped from the Assemblies of God denomination for his determination to maintain a dialogue with the World Council of Churches, which was seen as too flawed to ever succeed.

During the Cold War, it was alleged to be a target of the KGB, which

Yet the World Council of Churches has survived, based in Geneva, Switzerland.

“At least once a year,” the WCC offers on its website, “many Christians become aware of the great diversity of ways of adoring God. Hearts are touched, and people realize that their neighbors’ ways are not so strange.

“The event that touches off this special experience is something called the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity.

“Traditionally celebrated between 18-25 January (in the northern hemisphere) or at Pentecost (in the southern hemisphere), the Week of Prayer enters into congregations and parishes all over the world. Pulpits are exchanged, and special ecumenical worship services are arranged.

“Ecumenical partners in a particular region are asked to prepare a basic text on a biblical theme. Then an international group with WCC-sponsored (Protestant and Orthodox) and Roman Catholic participants edits this text and ensures that it is linked with the search for the unity of the church.”

Roman Catholic? Really?

A check with local parish priests verifies that the Catholic Church’s policy of not inviting non-Catholic clergy to speak from Catholic pulpits stands. However, priests throughout the U.S. have been reminded by their bishops that they are permitted to mention the Week of Prayer in their sermons and include the goals for Christian unity in their prayers.

The WCC website notes that the text from which sermons can be based has been jointly published by the Vatican’s Pontifical Council for Promoting Christian Unity and the WCC “and has been sent to Roman Catholic dioceses” and “they are invited to translate the text and contextualize it for their own use.”

The Week of Prayer was the brainchild in 1908 of Spencer Jones, the Anglican Vicar of Moreton-in-Marsh Church in England and his friend and fellow Church of England clergyman Paul Wattson, together with Lurana White. In 1909, Wattson and White converted to Catholicism and cofounded the Franciscan Friars and Sisters of the Atonement. Wattson and White believed that Christian unity could only be achieved by the other churches returning to the Roman Catholic fold – which remains the official Catholic position.

The event caught on during the 1930s through the work of a French Roman Catholic, Paul Couturier, who did not believe that it was necessary for all Christians to become Catholic. He taught that “we must pray not that others may be converted to us but that we may all be drawn closer to Christ.”

Although the strain between the various branches of Christianity is difficult much of the time, “The desire for Christian unity – which is the real spark behind the ecumenical movement – originates in the heart of Christ,” notes an editorial supporting the Week of Prayer in the Catholic magazine St. Anthony’s Messenger.

“Jesus’ fervent desire is expressed clearly in the prayer he uttered at the Last Supper. Speaking of the beloved disciples whom His loving Father entrusted into His care, Jesus prays, ‘Holy Father, keep them in your name that you have given me, so that they may be one just as we are’ (John 17:11).

“A few verses later, Jesus expands this prayer with a rich addition: ‘I pray not only for them, but also for those who will believe in me through their word, so that they may all be one, as you, Father, are in

“Prayer is an important way to start any human project,” continues the St. Anthony’s Messenger editorial, “as the opening verse of Psalm 127 asserts: “Unless the Lord build the house, they labor in vain who build it.” How much more does this apply to the urgent cause of building up the “House of Christian Unity”! Unless Christ helps build this house, we truly work in vain.”

This first celebration of Wattson’s Week of Prayer “took place in the chapel of a small Franciscan convent of the Episcopal Church, on a hillside 50 miles north of New York City,” notes the Messenger.

“Father Wattson and other members of the Atonement Friars and Sisters – and other Anglicans – felt that the Church of England should regain its Catholic identity by seeking some kind of ‘reunion’ with the Bishop of Rome. The Atonement Friars and Sisters found their answer for unity withRomeby entering into full communion in 1909.

“From the start, however, Father Wattson’s group drew opposition for his idea by choosing January 18 (then the feast of St. Peter’s Chair atRome) as the beginning of the annual prayer period.

“The ‘return to Rome’ approach predictably alienated many Protestant as well as Orthodox Christians.

“But as the decades passed, solutions were introduced that helped offset feelings of alienation. In the 1930s, for example, Couturier took a different tack. He advocated praying for the unity of the Church ‘as Christ willed it.’

A recent gathering of the World Council of Churches

“More difficulties were resolved in 1964 when the Second Vatican Council issued its Decree on Ecumenism. The Decree encouraged Catholics to ‘join in prayer with their separated brethren’ – and to recognize the spiritual gifts of other communities of Christians.

“Changes like these paved the way for a more cooperative spirit and a wider acceptance.”

Wattson had called the event the “Octave of Prayer for Christian Unity” – since it spanned eight days. In 1968, the name was changed to its current title.

How has it survived?

“Christians are supposed to be together!” writes James Loughram. “The movement among Christians promoting Christian unity, as everyone knows, is the ecumenical movement. It is the Church’s attempt to practice what Our Lord prayed for on the night before he died for us, ‘That they may all be one as you, Father, are in me and I in you, that they also may be in us, that the world may believe that you sent me’ (John 17:21).

“The Father will answer the Son’s prayer—we cannot do it on our own. The Father answers that prayer in the Holy Spirit, inspiring the hearts of believers to move away from needless division and towards unity.

“Now in its second century, the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity calls Christians together in fellowship to ‘pray without ceasing’ (1 Thessalonians 5:12a, 13b-18). Praying together, we are reminded that we are truly sisters and brothers in one baptism. We speak to God together through Christ in the power of the same Holy Spirit. When we leave the services of the Week of Prayer for Christian Unity, we hopefully experience a growth in spiritual fellowship and feel saddened

“It follows what is called the Lund Principle, named for Lund, Sweden, where the World Council of Churches first stated, in 1952, “Let us not do separately what we can do together.”

“In this way all Christians can already manifest the unity of the Church as much as possible. Empowered by the experience of praying together, we can also see how possible it is to join together to proclaim and bear witness to the gospel in the face of human suffering, war and social evil.”