My grandparents, Owen and Shirley Still

He preached in a church with a makeshift steeple — which Japanese security inspected regularly, certain it was atop the building for spying purposes — and drew crowds that came to hear his fluent Japanese spoken with a soft Atlanta, Georgia, drawl.

My mom and her sisters also annoyed police when they’d attract crowds of gawkers by doing innocent things like going roller-skating in downtown Tokyo with metal clamp-on skates mailed by relatives.

Just weeks before December 7, the family had gotten an urgent message from the U.S. Embassy to evacuate to a luxury liner the U.S. Navy had commandeered in the mid-Pacific and sent to pick up American citizens in Tokyo. They and hundreds of other Americans were near-refugees – allowed only two pieces of baggage and crammed into every spare space of the ship, which then picked up more Americans and British in Shanghai and Hong Kong – dropping them off in Australia to find their own way home.

Japanese Zero aircraft on deck of the Shokaku

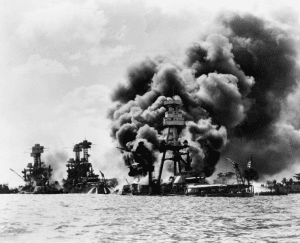

The Still family had made it back to the U.S. and my grandfather had taken a professorship at a college in Bentonville, Arkansas, when the announcement came over the radio. Japan had launched a sneak attack against the U.S. Pacific Fleet anchored in Pearl Harbor, Hawaii – as well as American and British forces in the Philippines, Singapore, Malaysia and Hong Kong.

A Japanese task force of six aircraft carriers, the Akagi, Kaga, Soryu, Hiryu, Shokaku and Zuikaku had launched 408 aircraft against Hawaii. The first wave targeted high-value targets — battleships and aircraft carriers, then cruisers and destroyers. Dive bombers strafed

The West Virginia, Tennessee and Arizona

Their mission was to destroy the U.S. Pacific Fleet and prevent America from interfering in the Empire of Japan’s expansion into China as well as the Pacific Rim territories of the United Kingdom, the Netherlands and the United States.

All eight U.S. battleships were damaged — four sunk. However, all the U.S. aircraft carriers were at sea. The Japanese also sank or damaged three cruisers, three destroyers, an anti-aircraft training ship and a minelayer and destroyed 188 U.S. aircraft . In the attack, 2,402 Americans were killed and 1,282 wounded. Japanese losses were light: 29 aircraft and five midget submarines lost, and 65 servicemen killed or wounded. One Japanese sailor was captured.

Of the American fatalities, nearly half of the total — 1,177 — were due to the explosion of the battleship U.S.S. Arizona‘s forward ammunition magazine after it was hit by a Japanese bomb.

The U.S.S. Arizona memorial today

Damaged and afire, the battleship U.S.S. Nevada attempted to escape the harbor and was targeted by Japanese bombers hoping she could be sunk strategically, blocking the harbor entrance.

The U.S.S. California was hit by two bombs and two torpedoes. The crew might have kept her afloat, but were ordered to abandon ship just as they were getting the pumps to work. Smoke from the Arizona and the battleship U.S.S. West Virginia had drifted over her, making her situation look worse than it was. The U.S.S. Utah was hit twice by torpedoes, the West Virginia seven times, the last one tearing away her rudder.

The mighty U.S.S. Oklahoma was capsized. The U.S.S. Maryland was hit twice, but not seriously damaged.

Eight U.S. Army Air Corps pilots managed to get airborne during the battle and six were credited with downing at least one Japanese aircraft each.

The attack came as a profound shock to the American people. A deep domestic yearning to stay neutral from the war raging in Europe evaporated, particularly after Nazi Germany and Mussolini’s Italy declared war on the U.S. on December 11.

President Roosevelt delivering his "Day of Infamy" speech

There might be historical precedents for such an unannounced military action by Japan – a “sneak attack.” However, the lack of any formal warning, particularly while peace negotiations were ongoing in Washington, D.C., led President Franklin D. Roosevelt to proclaim to Congress that December 7, 1941, would forever be ”a date which will live in infamy.”

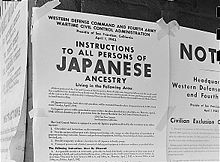

My grandfather was infuriated by the sneak attack – but heartsick over the reaction against U.S.-born Japanese-Americans. Within weeks of the attack, American citizens of Japanese ancestry were rounded up

The notice ordering Japanese into camps

My grandfather was so appalled that he took his family out into the desert for most of the war, living at camps in California and at Casa Grande, Arizona. Toward the end of the war, they ended up in Gunnison, Utah, when some Japanese-Americans were permitted to live outside of the barbed wire as tensions eased.

Internned Japanese-American kids recite the Pledge of Allegiance

A loyal, patriotic American, my grandfather came under severe criticism. There was little financial support for a missionary who seemingly had taken the side of the enemy. Yet, he was convinced these heartbroken Americans whose ancestors had immigrated decades earlier were no enemy. Any who wished to return to Japan were given free passage back there. The ones in the U.S. internment camps wanted nothing to do with an empire on the other side of the world that had attacked their native homeland.

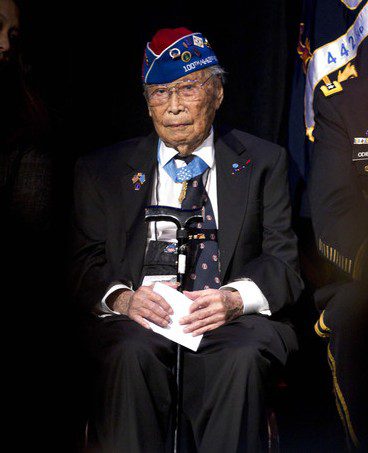

Congressional Medal of Honor winner George Sakako at a recent ceremony

Out of those relocation camps came the 442nd Regimental Combat Team of the United States Army — composed of Japanese-American enlisted men who pleaded to be allowed to join the battle. Although their families were in internment camps in the desert, the 442nd fought with distinction in Italy, southern France and Germany. They became the most highly–decorated regiment in the history of the United States armed forces, earnintg over 18,000 individual medals, including 9,000 Purple Hearts, over 4,000 Silver Stars, 560 Silver Stars, 52 Distinguished Service Crosses, 22 Legions of Merit and 21 Congressional Medals of Honor.

Today on my mom’s wall is an Easter lily plaque carved by hand and painted by one of the Japanese-Americans from a piece of scrap lumber. She quietly looks at it from time to time, remembering that day in December 1941 when her world – and that of millions of others — turned upside down as the U.S. Pacific Fleet burned in the oily waters of Pearl Harbor.