The plaza today

Edwardo Suarez of the prestigious Mexico City architectural firm BNKR Arquitectura wants to burrow under the Mexican capital’s most famous square, the historic Zócalo — Mexico City’s Plaza de la Constitución — and highlight Mexico’s rich Aztec and Christian heritages with a 10-story underground museum, which would include new archeological discoveries unearthed in the excavation process. Then the 55 stories beneath the museum would be retail, office and even living space — ringed with garden terraces.

The Zócalo was built 500 years ago shortly after the Spanish conquest. After the destruction of the Aztec capital of Tenochtitlan, Hernan Cortés destroyed the central pyramid where he witnessed scores of human sacrifices — in which prisoners of war were hauled to the top of the Templo Mayor and their living hearts were cut from their chests, their bodies tossed down the steps. Horrified, Cortés banned the practice, had the pyramid razed to the ground, with its stones paved today’s plaze and built a Catholic church which today is Mexico’s National Cathedral.

Around the Zócalo today, portions of the Templo Mayor have been restored. Facing the plaza is the National Palace — Mexico’s seat of government. For half a millenium, the Zócalo has been the site of the swearing in of viceroys and presidents, as well as the setting for

national proclamations, military parades and historic ceremonies. It is here that Mexico receives foreign heads of state — and where in times of discontent, crowds gather to protest.

The proposal is to dig out the center of the 188,976-square-foot Zócalo, and burrow down almost 1,000 feet.

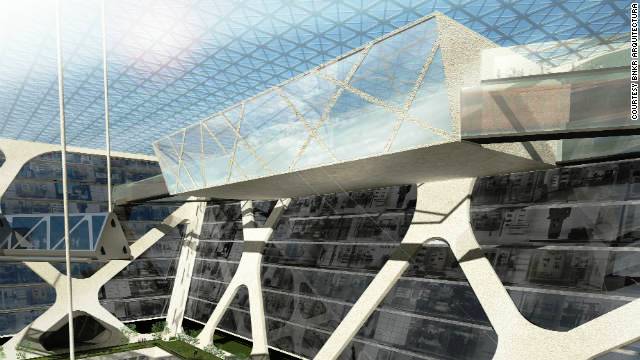

“A team of Mexican architects have designed a 65-story glass and steel pyramid to sit in the middle of Mexico City’s most historic plaza. But, if it ever gets built, you won’t see it anywhere on the skyline,” reports CNN’s George Webster. “If built, the 65-story ‘Earthscraper’ would plunge 300 meters into the ground.”

A glass-covered, open atrium would bring in sunshine and fresh air — as would terraced gardens, called “earth lobbies.” says Suarez. The terraces would be filled with plants and trees to freshen the air.

“Earthscraper has become the architectural equivalent of a shot heard ’round the world,” writes Emily Gertz on the website Ecomagination. ”This conceptual design for a 65-story inverted pyramid underneath Mexico City now commands over a quarter-million stories in diverse publications around the globe.

“Why has the experimental skyscraper design, created for a 2009 “Skyscrapers of the Future” competition in the architecture magazine eVolo, attracted so much attention?” asks Gertz.

What the plaza would look like at night

“We were expecting to have some controversy,” says Emilio Barjau, Chief Design Officer and Design Director of BNKR Arquitectura, the Mexico City firm that created the concept. “But this recent boom is really amazing, it really surprised us. We were not expecting this to be all over news.”

Barjau thinks that Earthscraper may have burst the bounds

of the architectural world because it has taken a truly new approach to escalating megacity problems like planning for population growth, curbing sprawl, preserving open space, and conserving energy and water.

In the process, however, the concept also incorporates respect for the city’s past, by seeking to integrate the centuries of Mexico City’s history into its proposed solutions to present and future problems, rather than obliterate them.

A conceptual drawing of the proposed museum

Furthermore, it would be accessed directly from Mexico City’s underground subway system, preventing congestion above ground.

“It would turn the modern high-rise, quite literally, on its head,” notes CNN’s Webster.

“There is very little room for any more buildings in Mexico City,” explains Suarez, “and the law says we cannot go above eight stories, so the only way is down. This would be a practical way of conserving the built environment while creating much-needed new space for commerce and living.”

“But,” wonders Webster, ”would it really be that practical? The design, which would cost an estimated $800 million to build, is the shape of an inverted pyramid. Suarez says the first 10 stories would hold a museum dedicated to the city’s history and its artifacts. ”

The terraced gardens would be public parks

“We’d almost certainly find plenty of interesting relics during the dig —

The following 10 floors are assigned to retail and housing, with the remaining 35 intended for commercial office space.

Mexico City is the second-largest urban agglomeration in the western hemisphere—a tad smaller than Sao Paolo, noted Gertz, “but bigger than New York City. Home to around 9 million people within its official 573 square miles and with about 19 million in the greater metropolitan area, it is among the world’s top ten “global cities,” a crucial hub of international commerce, finance, and culture.

“BNKR sited the Earthscraper design on Mexico City’s major public plaza in part because the space is the city’s historic, cultural, and physical heart. Once the site of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan, the plaza hosts year-round civic events including concerts, exhibits, public demonstrations, parades, and more.

A conceptual drawing of the glassed-over plaza

At a massive 188,976 square feet, the Zocalo is also one of the few sizable open spaces left in Mexico City, a hard-to-resist lure for architectural dreams. But it comes with extremely restrictive zoning codes aimed at preserving surrounding landmarks, including the Metropolitan Cathedral, the National Palace, and nearby remains of Templo Mayor, a significant Aztec temple.

The building restrictions render the area “under-developed,” says Barjau. But the only direction to go is down.

“The Earthscraper concept begins with a glass roof replacing the opaque stone surface of the Zocalo,” writes Gertz. “This ‘ceiling’ preserves the open space and civic uses of the Zocalo, while allowing natural lighting to flow downward into all floors of the tapering structure through clear or translucent core walls.

The inverted tower’s first 10 stories would be dedicated to a museum displaying the different layers of Mexico City that an actual excavation would reveal.

“They used to build one city on top of the other, since pre-Columbian times,” says Barjau. “So we’d have layers of different artifacts and other elements that we will find,” perhaps in part by showing the surrounding underground through clear glass walls.

He says that the structrue would be insulated by earth and the terraced gardens would create “microclimates” inside the tower. Would clouds form? Would it rain inside the structure — like a giant terrarium?

“Some facets of the Earthscraper design are so conceptual as to need inventing,” writes Gertz. One of these would involve finding a way to build so deeply into the water-soaked soil which currently supports contemporary Mexico City. When the Aztecs first built Tenochtitlan in 1325, this area—a valley ringed by mountains and volcanoes that reach heights of over 16,000 feet—was mostly covered by Lake Texcoco, with no natural drainage.

The Aztecs expanded Tenochtitlan’s area by filling the lake immediately around it, and created dam and channel systems to control the lake’s height.

Another conceptual view

“It’s a project that actually has a chance to get built,” writes Gertz.

These problems are a major reality-check to the Earthscraper concept, says R. David Scheer, an architect and energy modeler with the design software firm Autodesk. “It’s a really bold proposal that deals with an iconic location in Mexico City,” he says. “It would be nice to see them address some of the realities of building services. How would they pump up all the waste? How are they going to get water down there?”

Barjau agrees that groundwater and wastewater issues are among the design’s major challenges, writes Gertz. “We would need to have new technologies in order to make this building actually work,” he says. “There might be ways to use the water around the site, filter it, use it in the building, then maybe return it to the earth.”

These and other critiques of Earthscraper may have some potential to be more than further variations on a thought experiment, according to Barjau. “The project started as a proposal for a competition, an exploration of what we could do to solve several problems for Mexico,” he says. But thanks to all the attention it’s receiving, “now it’s a project that actually has a chance to get built.”

Underneath the glassed-over plaza