“You’re just talking; you’re not doing anything!” she said, and stalked off.

That was the difference between my late sister and me, at least when it came to God. Ruthie and I were both Christians, but we approached our faith in very different ways.

I am intellectual and contemplative. Nothing makes me happier than thinking through a theological problem, turning it over in my mind, and talking it out with others. I have been spiritually restless, leaving the Methodist church of our youth for Catholicism, and then for Eastern Orthodoxy. My faith has been mostly in my head.

Ruthie was emotional and active. She never questioned what the Bible said, or the settled tradition our parents handed to us. For Ruthie, faith was what you did. Her faith was in her heart.

To be fair to both of us, there is a place for both approaches to the Christian life. God gave us minds, and intends us to use them to understand Him and the world he created. I doubt Ruthie, who was a teacher, would have disagreed, but she took a dim view of abstract intellectual inquiry, at least on theological matters. To her, what really mattered was not what you thought about God, but what you did for His sake.

For years after my Catholic conversion, I thought I was immersing myself in the Christian life by thinking and talking about theology. When I was put to the test, during the Catholic abuse scandal, I learned only too late that I ought to have spent more time praying instead of intellectualizing. I was a spiritual shipwreck.

Ruthie’s theology didn’t go much beyond Jesus loves me, this I know, for the Bible tells me so. But when she was put to the test by terminal cancer, she endured it with unshakable faith, calm, and compassion – the same compassion with which she lived her life.

Watching Ruthie walk across fire with a smile on her face, I realized that if I were to receive the same diagnosis, I would read every theological volume on my shelves, consult clergy and sages, agonize over every aspect of my illness and its philosophical implications … and if I was lucky, I would end up exactly where Ruthie started: totally surrendering to God and trusting in His love.

After I lost my Catholic faith, in large part due to the weakness of my own favored intellectual style of religion, God gave me a second chance as an Orthodox Christian. Orthodoxy has a profound and ancient theology. One of its key insights is that knowing God with one’s heart is the key to holiness. Formal study is fine, but it is no substitute for prayer and the practice of mercy and compassion.

In classic Orthodox Christianity, a “theologian” is one who knows God. Silouan, a monk of Mount Athos, could barely read, yet so great was his holiness and humility that he is considered one of the great Orthodox theologians of the 20th century. In this sense, my sister Ruthie, a simple Methodist country schoolteacher, is one of the greatest theologians I have ever known.

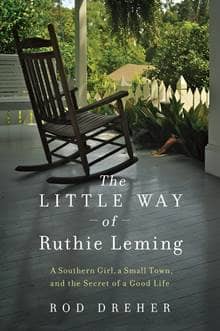

Rod Dreher is a Beliefnet columnist and the author of The Little Way Of Ruthie Leming, which has just been published by Grand Central. Follow him on Twitter @roddreher, or connect with him at the Rod Dreher fan page on Facebook.