If you’re Muslim, and you have diabetes, can you still fast?

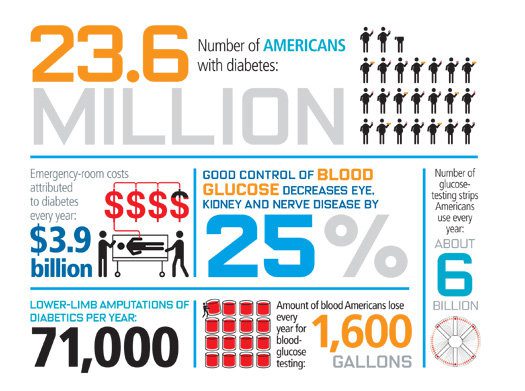

That’s a question that more and more Muslims ask themselves each year, as the diabetes epidemic in America and worldwide continues. According to a 2011 report by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 26 million Americans have diabetes and 79 million have prediabetes, up from 24 million and 57 million in 2008, respectively. That’s 11% of all Americans over the age of 20, and 27% of all people over the age of 65. Over 30% of all Americans over the age of 20 have prediabetes. The African-American community in particular is hit hard by diabetes: 5 million people, or 19% of all non-hispanic blacks over age 20 are diagnosed with the disease. For the Asian-American community it’s 8.5%, which is still higher than the rate for non-Hispanic whites (7%). And these numbers increase every year.

Given that blacks and asians comprise roughly half the Muslim American population, it’s clear that diabetes is a major concern for our communities. It’s likely that every muslim in America knows at least one person with diabetes in their family or in their mosque.

So, what’s the answer? There is actually a fairly large amount of data and scientific study on the metabolism of the fasting muslim, much of it available to the public at PubMed. And the consensus seems to be, the answer is Yes, you can indeed fast: if you’re careful.

I’m not a physician, of course, so please do not construe this post as medical advice. What I intend to do is to just highlight some of the scientific findings out there that seem useful and relevant. If you have diabetes, you should talk to your doctor first before starting the fasts. And of course remember that the Qur’an specifically exempts travelers and the sick from fasting. Use your best judgement!

OVERVIEW

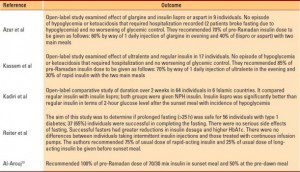

So, let’s take a look at what’s out there. For example, in a 2011 review paper in the Annuals of Saudi Medicine by Ahmed et al, there is this rather handy flowchart (click to enlarge):

(The difference between Type 1 and Type 1 diabetes is explained here)

Note the reference to Table 1 for the Type 1 patients – here is that table, laying out other published recommendations in the literature on varying insulin regimens (click to enlarge):

The main strategy seems to be adjusting medication for Type 2 patients and varying insulin injections for Type 1. However, fasting is inherently riskier for Type 1 diabetes patients than for those with Type 2. For example, a 2008 paper in Clinical Therapeutics by Kobeissy et al notes the danger signs:

Patients who observe the fast should be advised to monitor their blood glucose regularly,avoid skipping meals or overeating,and maintain contact with their physician throughout the fast. The fast should be broken immediately if blood glucose drops below 60 mg/dL (3.3 mmol/L). Breaking the fast should be considered when blood glucose drops below 80 mg/dL (4.4 mmol/L), and the fast should be interrupted if blood glucose rises above 300 mg/dL (16.7 mmol/L) to avoid diabetic ketoacidosis.

TYPE 1 DIABETES

The review paper also notes that Type 1 patients with poorly controlled diabetes, or with comorbid conditions like unstable angina, should not fast under any circumstances. Likewise, diabetic patients with established renal disease of any type should not fast (ref).

One of the landmark references in this field is this 2005 paper in Diabetes Care, which concludes:

In general, patients with type 1 diabetes should be strongly advised to not fast. Patients with type 1 diabetes who have a history of recurrent hypoglycemia or hypoglycemia unawareness or who are poorly controlled are at very high risk for developing severe hypoglycemia. On the other hand, an excessive reduction in the insulin dosage in these patients (to prevent hypoglycemia) may place them at risk for hyperglycemia and diabetic ketoacidosis. Hypo- and hyperglycemia may also occur in patients with type 2 diabetes but generally less frequently and with less severe consequences compared with patients with type 1 diabetes. A patient’s decision to fast should be made after ample discussion with his or her physician concerning the risks involved. Patients who insist on fasting should undergo pre-Ramadan assessment and receive appropriate education and instructions related to physical activity, meal planning, glucose monitoring, and dosage and timing of medications. The management plan must be highly individualized. Close follow-up is essential to reduce the risk for development of complications.

They also note in the Results,

It is unlikely that one injection of intermediate- or long-acting insulin administered before the evening meal would provide adequate insulin coverage for 24 h. Typically, patients will need to use two daily injections of NPH as intermediate-acting insulin, administered before the predawn and sunset meals, in combination with a short-acting insulin to cover food intake at the associated meals. However, there is an increased risk of hypoglycemia around midday due to peaking of the early morning insulin dose. Using the long-acting insulin ultralente is an option, with twice-daily injections at ?12-h intervals to mimic basal insulin, and a rapid- or short-acting insulin should be added before the two meals. Still, ultralente cannot be considered truly basal insulin, since it has a broad peak of action at ?8–14 h. Therefore, protracted hypoglycemia can occur, especially since ultralente exhibits wide variability in its duration of action (18–30 h).

Another option would be to use one daily injection of the long-acting insulin analog glargine or twice-daily injections of the insulin analog detemir along with premeal rapid-acting insulin analogs.

(Note that the flowchart above also recommends the insulin glargine approach. That paper was actually a review that sought to integrate diabetes recommendations from numerous previous papers, including this one).

TYPE 2 DIABETES

The same 2005 paper has this to say about Type 2 diabetes patients:

In patients with type 2 diabetes who are well controlled with diet alone, the risk associated with fasting is quite low. However, there is still a potential risk for occurrence of postprandial hyperglycemia after the predawn and sunset meals if patients overindulge in eating. Distributing calories over two to three smaller meals during the nonfasting interval may help prevent excessive postprandial hyperglycemia. Patients controlled with diet alone usually combine this with a regular daily exercise program. The exercise program should be modified in its intensity and timing to avoid hypoglycemic episodes; the timing of the exercise could be changed to ?2 h after the sunset meal. Finally, in this usually older age-group, often with hypertension and dyslipidemia, fluid restriction and dehydration may increase the risk of thrombotic events

EXERCISE

With respect to exercise for fasting diabetics, the 2005 paper says,

Normal levels of physical activity may be maintained. However, excessive physical activity may lead to higher risk of hypoglycemia and should be avoided, particularly during the few hours before the sunset meal. If Tarawaih prayer (multiple prayers after the sunset meal) is performed, then it should be considered a part of the daily exercise program. In some patients with poorly controlled type 1 diabetes, exercise may lead to extreme hyperglycemia.

Presumably the same goes for tahajjud prayer – it can be counted as part of the daily exercise regimen.

DIET

Finally, nutrition recommendations are as follows:

The diet during Ramadan should not differ significantly from a healthy and balanced diet. It should aim at maintaining a constant body mass. In most studies, 50–60% of individuals who fast maintain their body weight during the month, while 20–25% either gain or lose weight (4); occasionally, the weight loss may be excessive (>3 kg). The common practice of ingesting large amounts of foods rich in carbohydrate and fat, especially at the sunset meal, should be avoided. Because of the delay in digestion and absorption, ingestion of foods containing “complex” carbohydrates may be advisable at the predawn meal, while foods with more simple carbohydrates may be more appropriate at the sunset meal. It is also recommended that fluid intake be increased during nonfasting hours and that the predawn meal be taken as late as possible before the start of the daily fast.

However, note that a comment on this paper advised that clinical studies have found that there is no real difference in digestion rates between simple and complex carbohydrates, so it shouldn’t make any difference.

SUMMARY

- TALK TO YOUR DOCTOR BEFORE RAMADAN STARTS ABOUT YOUR INTENTION TO FAST.

- if you have Type 1 diabetes, then you should NOT fast if you also have renal disease or other chronic ailments. If you don’t, then there are variable insulin regimens you can follow – ask your doctor.

- For Type 2 diabetes, don’t overeat, better to break up your post-fasting meals into smaller portions, and make sure you excercise (Tarawih or tahajjud count). There may be some adjustments to your oral meds.

- For everyone: drink a LOT of water and use common sense on your diet (easy on the iftaar sweets!)

This is of course an information overload. But I think it provides a starting point for the diabetic Muslim to educate themselves on the basics of managing their diabetes during Ramadan, in advance of consultation with their own physician. If there are any physicians reading this post I would certainly welcome your feedback as comments to the post or email me, at apoonawa-blog at yahoo dot com.

Related references: The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) diabetes fact sheet (2011). Also, there was a comprehensive, multi-country study called EPIDIAR in 2001 that collected a lot of data and which most subsequent studies on diabetes during Ramadan do draw upon.