Great humor often sparkles on the surface of a dark tide of challenge or tragedy. Mark Twain, still America’s most beloved humorist, was stricken by many terrible events in his life and that of his family – the loss of a beloved brother and later his favorite daughter, the loss of all his money late in life, forcing him to start over – yet generally managed to come back laughing, and making the rest of us laugh.

Great humor often sparkles on the surface of a dark tide of challenge or tragedy. Mark Twain, still America’s most beloved humorist, was stricken by many terrible events in his life and that of his family – the loss of a beloved brother and later his favorite daughter, the loss of all his money late in life, forcing him to start over – yet generally managed to come back laughing, and making the rest of us laugh.

His ability to laugh his way through did not mean numbing himself to tragedy. Sam Clemens (who adopted the pen name Mark Twain) dreamed the death of his younger brother Henry before it took place, in exact detail, and this haunted him for the rest of his life..

Sam and Henry were set to embark together on the riverboat Pennsylvania, Sam as apprentice pilot, Henry as a lowly “mud clerk”, given food and sleeping space in return for helping out at places on the river where there were no proper landing sites. The night before they sailed, Sam dreamed he saw Henry as a corpse, laid out in a metal casket, dressed in one of his older brother’s suits, with a huge bouquet of white roses on his chest and a single red rose at the center.

Sam woke grief-stricken, convinced this had actually happened and that Henry was laid out in the next room. He could not collect himself, or convince himself that the dream was not “real” until he had walked around outside. He had walked a whole block, he recalled, “before it suddenly flashed on me that there was nothing real about this – it was only a dream.”

Family members urged him to dismiss his terrible dream; after all, it was “only a dream”. Though the force of his feelings told him something else, Sam agreed to try to put the dream out of his mind.

The tragedy began to unfold soon after the two young men boarded the Pennsylvania. The pilot of the Pennsylvania, William Brown, was an autocrat with a violent temper with whom Sam was soon scrapping. During the voyage downriver, Sam got into a full-blown fight with him. The captain sided with Sam, and said they would find a new pilot when they got to New Orleans. But a new pilot could not be found and since Sam and Brown could not coexist on the same boat, Sam was transferred to another vessel, leaving Henry on the Pennsylvania, which started the upriver journey fist. Just before they parted company, Sam and Henry discussed how they would act in the event of a riverboat disaster such as a boiler explosion, which was a common occurrence.

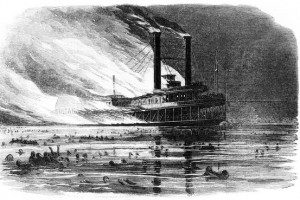

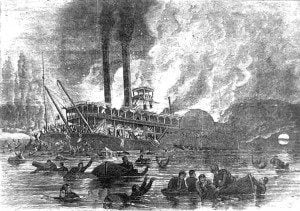

The Pennsylvania’s boiler exploded in a hell of steam and fire, in the way they had discussed. Badly burned, Henry survived for a few days, to die in Memphis, where the injured were carried. His handsome face was untouched, and the kindly lady volunteers were so moved by his beauty and innocence that they gave him the best casket, a metal box.

When Sam entered the “dead-room” of the Memphis Exchange on June 21, 1858, he was horrified to see the enactment of his dream: his dead brother laid out in a metal casket in a borrowed suit. Only one element was missing: the floral bouquet. As Sam watched and mourned, a lady came in with a bouquet of white roses with a single red one at the center and laid it on Henry’s chest.

Mark Twain kept telling and retelling the circumstances of Henry’s death, in his mind and in his writing, for the rest of his life. He was one of the first to join the Society for Psychical Research after it was founded in London in 1882 in the hope that its investigators could help him understand the workings of dream precognition. He could never escape the thought that – had he only known how to use the information from his dream – he might have been able to prevent Henry’s death.

~

For more on Mark Twain’s dreams and his study of coincidence and what he called “mental telegraphy,” please read the chapter titled “Mark Twain’s Rhyming Life” in my Secret History of Dreaming, published by New World Library.