Clive Staples Lewis is an author celebrated and beloved the world over, remembered not only for his meaningful fiction, but for the strength of his written work in Christian apologetics.

His work wells up from the deep roots of his faith, and flows forth from an imagination that took that faith and transformed it into stories and wisdom.

But from where did the distinctly Christian imagination of C.S. Lewis come? There lies a clue in a line Lewis’s book, “Surprised by Joy”.

“A young man who wishes to remain a sound Atheist cannot be too careful of his reading.”

When he wrote this sentence, Lewis was thinking of one man—George Macdonald.

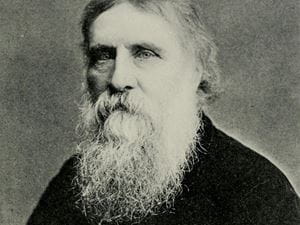

Born 1824, MacDonald was a Scottish minister, author, and poet. He was also a pioneer of fantasy literature, and a major influence on such writers as J.R.R. Tolkien, Walter de la Mare, and Madeleine L’Engle.

But he influenced none, perhaps, as much as he did Lewis, who came to consider MacDonald his literary and spiritual mentor.

In October of 1916, a 16-year old Lewis pored over the books at a railway station bookseller’s stall, the sound of steam engines chugging away behind him and the voice of the porter floating on the air.

A certain book finally caught his attention—in his own words, an “Everyman in a dirty jacket”. The title was just alluring enough to warrant a look.

That book turned out to be George MacDonald’s faerie masterpiece, “Phantastes”. That evening, Lewis settled in—likely, with a good cup of tea—to enjoy this new piece of literature. What he found in the narrative, in which ordinary life is transformed into the world of faerie, were all the qualities of the sort of literature he loved, but also something more that he could not quite put a finger on.

Later in life, Lewis, in “Surprised by Joy,” would write of that night, saying, “It was as if I were carried sleeping across the frontier, or as if I had died in the old country and could never remember how I came alive in the new... I did not yet know (and I was long in learning) the name of the new quality, the bright shadow, that rested on the travels of Anodos. I do now. It was Holiness... It was as though the voice which had called to me from the world’s end were now speaking at my side.” The discovery of George MacDonald was the catalyst that began a chain of events in Lewis’s life that eventually led him out of atheism and into Christianity.

It might seem strange that fantasy could lead a man to God, but Lewis writes that MacDonald’s fantastical realms acted to “convert, even to baptize my imagination”. As Lewis read more of MacDonald’s work, he began to understand that “new quality” he could never quite put a finger on wasn’t separate from MacDonald’s faith, but rather was an essential part of it.

Fantasy literature has the unique ability to take a real-world concept and divorce it from its familiar moorings. Real wars become imaginary quests. The lust for power takes the form of an irresistible magical ring. Human greed becomes a dragon. And so readers can learn about the most incredibly complex, beautiful, or frightening shades of humanity without every truly realizing it.

Or, as in Lewis’s case, a reader can be exposed to the goodness of God. Consider the parables of Christ—stories that convey truth about the nature of God through stories about the natural world. Fantasy is just as capable of illustrating the mystery and beauty of God and what lies beyond death, but it does so by arresting our attention with stories of the fantastic rather than the natural.

This is exactly what MacDonald’s work does.

Unable to resist these new ideas about the divine, C.S. Lewis finally capitulated in 1929, when he knelt and accepted God as God. Within a few years of his conversion, Lewis published “The Pilgrim’s Regress,” the first a 30-year stream of Christian apologetics works.

Lewis’s turn to God also brought us such long-enduring works of fiction as “The Screwtape Letters,” “The Chronicles of Narnia,” and “The Great Divorce”.

Without the influence of MacDonald’s sanctifying fantasies, we would likely have none of these timeless works. The name of C.S. Lewis might have been relegated to an occasional footnote on the employment records of Oxford University.

And so who was this man who gave the world the C.S. Lewis we love today—this George MacDonald? Rarely do we see his name appear in the canonical lists of great writers every college student studies. Surprisingly, for such a prolific author, and as the man whom C.S. Lewis quoted in nearly every work, MacDonald has lapsed into relative obscurity today.

MacDonald was a man fascinated with God’s ability to love. Born to Calvinist parents, he attended King’s College in Aberdeen, Scotland. Going on to Highbury Theological College, he received a divinity degree, and settled into the role of pastor upon graduating.

Never satisfied with Calvinism’s doctrine of election—the idea that a select number of people are predestined for heaven, while others are predestined for hell—MacDonald embraced the idea that everyone would eventually go on to be with God, and that hell was a temporary place of redemptive suffering.

His role as pastor didn’t last long, however. Within three years, he was forced to resign over theological differences, never again to lead a church.

His writing life, however, took off, and between 1851 and 1897, MacDonald authored over 50 books across a variety of genres—novels, sermons, essays, fairy tales, and plays. During this time, he found a close friend in Lewis Carroll, author of “Alice in Wonderland,” who gave MacDonald the very first manuscript of his famous novel. Other British legends of literature—including Lord Tennyson and Matthew Arnold—were among his admirers, and even such faraway figures as Mark Twain and Ralph Waldo Emerson grew to like him.

Although he eventually became an Anglican, his patience with the pretense of man-made religion was thin—he felt that ornate ceremony and rote rituals just got in between mankind and a personal encounter with God.

The most telling aspect of MacDonald’s worldview—and the one that likely seeped into his work the most—was that he believed that the Christian Church was not the only thing that revealed God, but rather that all creation reveals God all the time, that there is divine mystery inherent to everything.

It was this sense of, and delight in, beautiful mystery that likely enthralled C.S. Lewis, who went on to elaborate on this longing in “Mere Christianity,” giving us one of the most memorable quotes in all of Christian thought.

“If I find in myself desires which nothing in this world can satisfy, the only logical explanation is that I was made for another world.”