What follow is a transcript of an interview between Vince Horn (of Buddhist Geeks) and John Wellwood. I thought this interview would provide plenty of fodder for reflection on the role of conscious relationship in our spiritual practice. And of course, in light of Valentine’s Day, isn’t it a good idea to think about how we can train our minds so that we’re able to love our partners with fewer conditions and fears and boundaries. Enjoy!

What follow is a transcript of an interview between Vince Horn (of Buddhist Geeks) and John Wellwood. I thought this interview would provide plenty of fodder for reflection on the role of conscious relationship in our spiritual practice. And of course, in light of Valentine’s Day, isn’t it a good idea to think about how we can train our minds so that we’re able to love our partners with fewer conditions and fears and boundaries. Enjoy!

PS The most appropriate book to buy if you like what you read in this interview is his “Towards a Psychology of Awakening.” It is a terrific read and one of the only books that deeply examines the link between psychology and spiritual awakening. Buy it at the Beliefnet store.

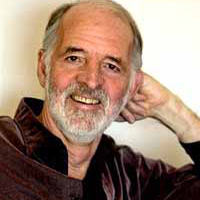

Vince: Hello, Buddhist Geeks! This is Vincent Horn and I’m joined today by Dr. John Welwood. John’s a clinical psychologist and psychotherapist and he’s really one of the key figures that have been working on how to bridge together Eastern and Western psychology, and also how to bring together, or how to work with conscious relationships. So, John, thank you so much for taking the time to speak with us. I really appreciate it.

John: Sure, I’m glad to be here.

Vince: Yeah. I figured it might be helpful to start with, just to hear how you got into both therapy and meditation. Because I know for me, being a child of the eighties, these things seem like they’ve always been together. But I know that when you were growing up, and that when you were getting interested in this stuff, they really weren’t as integrated as they are now.

John: You know, I was a child of the fifties and sixties. And so, the fifties and early sixties was an era of great alienation in America. It was like everybody was into their materialistic thing and there was not much going on in the area of psychology or spirituality. And I felt that very strongly about kind of meaninglessness of our culture, and sort of materialism and alienation of our culture. And so I was drawn to existentialism originally, as a way to adjust that.

And then, from there, I started to come into contact with books by D.T. Suzuki and Alan Watts. And those were the only things available really about Buddhism at that time. And one of Alan Watts’ books was called Psychotherapy East and West, and it was one of the first—he put together—he was one of the first people who actually really laid it out, and some sense of how, in his view, Western psychology, Western psychotherapy, could be an equivalent Western form of an Eastern path of awakening. And when I read that it kind of like blew my mind completely, it was like, I saw my destiny right there.

I felt like, this is the most important thing I can imagine. So, at the time I was a philosophy major in college and I started to take some psychology courses and I decided I’d go on in psychology. But, really my intent was to explore that question, because I was so taken by the early Zen Buddhist writings of Suzuki and Watts, and the idea of awakening and being able to step out of the cultural delusion that I felt like we were all in at the time. It just seemed so important to me.

And so I really approached psychology from the point of view, from the very beginning—I was looking for something that would help me answer those kinds of questions about how to wake up, what is the human being, how to be real, how do we deal with all our unconscious material, and all those sorts of questions. But basically, the question that kind of stayed with me throughout my years of graduate school in psychology—I became a clinical psychologist—but I was very much all the way through interested in the question—well, what’s the relationship between Buddhist awakening, or what was called satori in Zen at the time—and what was the relationship between that and the kind of change and growth that comes out of psychotherapy and psychological work? Are they the same thing, are they overlapping? Are they completely different things? That was the question that really was of main interest to me. And it still is these days, actually—my whole life.

Vince: Nice, thank you. And kind of connected to that, in this wonderful book that you wrote called Toward a Psychology of Awakening, you talk, in the very beginning, about a distinction between what we might call the realms of the “personal”, the “inter-personal”, and then what you call the “supra-personal”. And I found this really interesting and I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about these different realms and why they’re important?

John: I think most people hang out in one of those realms. I would say most people who are interested in meditation or Buddhism, spirituality, tend to be going more for supra-personal realization, or something that gets us out of the morass of the personal and the inter-personal, which is often seen as just samsara. So…and then people who do psychological work are more interested in the personal: what’s going on inside them, trying to understand that, trying to get to the root of things. And then, those people who just mainly hang out in the inter-personal: they do their marriage and family thing, and their thing is about being with other people, that’s what’s meaningful in their lives.

And so, often those three realms are split apart, people give main emphasis to one or the other of them. And I feel like it’s important—the big picture for me is it’s important for us to really start to understand and appreciate what a human being is, and what human being is possible of realizing in a lifetime. We’re only looking at one of those, or even two of those realms. We’re not complete. I personally think, for all our delusion and corruptnesses—that we see on our planet now in terms of the way human being are behaving—I think that’s partly because human beings don’t appreciate the incredible resources and beauty that exists within them, and in their relationships. And in all those three realms: inside themselves, potentially in their relationship with other people, and super-personally in relation to the absolute or to the transcendent or to the Buddha nature.

And if we realize what we have as human beings, and we realize this Earth is a Garden of Eden and we have everything we need to become completely happy, powerful, beautiful beings that are at peace and that are completely, you know, awake, basically. And so, I don’t think that’s going to happen unless we bring all those three realms together, however. And if we don’t, then spirituality becomes sort of separate from our life or from our relationships or if we just go out for relationships, that’s cut off from our spirituality, and they’re not conscious, they’re just kind of ways to try to make ourselves feel good. Or if you just go out for the personal apart from the interpersonal and supra-personal and you’re kind of just going endlessly into your own psyche and your own psychological material, and that’s a dead end, so. Part of this is, to me, articulating those three realms is to actually see the vast domain of what a human being spans. We have human-level, as human beings we also have access to levels beyond the human-level. And then we also exist in the context of relationships, all around us. Relationships to ourselves, relationships with other people, relationship to the universe, really, to the universal energies that are passing through us.

Vince: Yeah, and it’s so interesting when I think about bringing them together as part of the whole path. It’s so different from some of the original or early spiritual teachings where the idea was there’s nirvana and samsara. Samsara is like our personal and interpersonal—we basically want to get out of that.

John: That’s it. Most traditional spirituality and religion is about that, including Buddhism, really… it’s a… or, at least, many strains of Buddhism, are really about let’s… How do we get the hell out of here, and how do we get away from the Earthly mess, or the limitations or the conditioning? How do we rise above it, how do we go through it, move through it, how do we evolve beyond it? And I think the problem with that we’ve seen over time, over the centuries, is that spirituality then is then completely cut off from daily life, and our spirituality and religion is not transforming daily life. You can see after thousands of years, we’ve had thousands of years of Buddhas, people who’ve been waking up and having beautiful, transcendent realizations, but how much of it percolated down into daily life, and into the human realm of our lives and what’s going on on the planet? Not very much, I have to say. So I think the time is calling on us to say, if we want to survive as a species here, you’re going to have to really bring the largest truth down into the very heart of how you relate to other people and how you relate to yourself in a personal way as well.

Vince: You make the point in your book that in cultures like India, it was just totally okay to do that, to go into the supra-personal and to abandon the personal, so that there’s even a cultural, a norm around that, that supported that.

John: Right, yes, definitely. That’s the way it is in Asia.

Vince: That’s interesting. It seems like we just live in such a different cultural context.

John: We’re a completely different cultural context, which means I think that Buddhism really needs to evolve for our particular cultural context, otherwise it will just become like this hothouse flower, a beautiful thing that we just admire, but we don’t really embody.

Vince: Really connected to this, you write in your book that, “We in the West have been exposed to the most profound non-dual teachings and practices of the East for only a few short decades. Now that we’ve begun to digest and assimilate them, it’s time for a deeper dialogue between East and West in order to develop greater understanding about the relationship,”—like you’re talking about here—“between the impersonal absolute and the human personal, indeed expressing absolute true nature in a thoroughly personal human form may be one of the most important evolutionary potentials of the cross-fertilization of East and West, of contemplative and psychological understanding. I know this is what you’re talking about now, but it seems like such an important topic and one that we could probably talk about for a long time. Could you say more about why this is such an important dialogue?

John: You know, basically what we have often is a kind of one-sided spirituality, that’s where spirituality becomes one pole of life that’s set against the other pole of life. So you see Spirit and Matter, for example, or Religion and Worldly Life. In Buddhism, the same kind of split happens, and I see this especially often in Western students. It’s the absolute truth that’s cut off from relative truth, or the impersonal…meditation is seen as something impersonal like you’re going for some impersonal truth, then somehow you can’t relate it to your own personal experience, your own emotional life. Or you’re going through some kind of transcendence and you’re kind of leaving behind your own embodiment, you’re not actually living in your body, that’s very common. You know, I have a term for all of this, it’s called “spiritual bypassing”. We’re using spiritual ideas and practices to try to transcend or avoid dealing with our unfinished emotional business and our psychological wounding. We’re using absolute truth to dismiss or disparage relative human needs, feelings, relational problems, developmental tasks. That’s very common, I’d say in most spiritual communities that are based on Asian teachings, Eastern teachings.

So, my work is trying to correct that problem and show how on the one hand, psychological work is a very useful and practical and grounded way of actually connecting with yourself. And when you connect with yourself, in terms of your feeling level—life of feeling—and again I have to make a distinction between feeling and emotion, which is again a distinction that’s not really made in Buddhism. Buddhism generally relates to emotion and sees it as a problem, and I could see that too, but we also need to distinguish feeling.

Feeling, in that perspective is the life of the body, the intelligence of the body. It’s a holistic way of knowing. Often, we feel something, and it’s the way we know it, we can’t exactly articulate it, but we feel it, we know it in that way, we know it as feeling. A feeling is fluid, it’s alive, it’s dynamic, it actually helps us when we tune into it or go deeply into it, it actually helps us connect with ourselves more deeply. Emotion tends to be going outwards, like in seeking some sort of external expression. That’s why it’s called “e”motion, “e” here is short for Latin ex, which means out of some motion, out of, it’s motion taking us out of ourselves. And so, feeling is not really appreciated in spiritual traditions and psychologists are really, kind of specialized in how feeling is a doorway, and actually it’s not just a doorway that’s connecting to what’s really true for you on a personal level, but if you keep going with it, if you really go into your sadness or your pain or your anger or your frustration, underneath it you find not just personal truth, but at some level, you find, you really bring your presence, you can bring your meditative awareness into contact with the feeling life. And at some point, you’re actually opening doors into your own deepest nature, actually, because you find that, in the places where you were struggling…

Well, let me just give you an example, because it’s better to take an example. I have a client who is a practitioner, she’s a practitioner, maybe 30 years, but her practice is compartmentalized, it’s so split off from her emotional life, so she does the practice and she actually teaches in a community and her sangha. But, then, what she teaches is not really hooked up with what she’s actually experiencing. And so one day, we were looking at what was going on to her and she was stuck in this kind of victim state. Now, normally, we’d say, that’s a kind of bad place to be, and she was trying to get out of it, she was very judgmental of it and so forth. But my approach is that anything that arises in the psyche, in the mind, actually has intelligence operating it, some intelligence operating it. So we kind of kept looking at, well, let’s not judge it, let’s not try to get rid of it, let’s not try to fix it, let’s just go more deeply into it, that’s the approach I take [unintelligible]. I want to see what’s actually going on in there, feeling-wise.

And so I got in there, of course what she found was, of course, there was a sense of poor me, that was the story, poor me. That’s still not the feeling, that’s still not what the story is, so we keep going well, what’s the feeling? “Poor me.” And she got in touch with this deep, deep reservoir of sorrow, basically. And, this is a sorrow that went back actually to her very first days of being alive, her birth situation. And from then on, we looked at a lot of material in her life that she’d never grieved, basically, and so it had become what I’d call undigested material in her psyche. It was really clogging up her capacity to be present, to actually realize the teachings that she was teaching in the sangha. And until she actually, could actually meet and really directly experience that sorrow and actually honor it, because it has a deep truth in it, it had a deep truth in it, but she really needed to feel her own nature as love, really. And she never, through her childhood experience with her family, she’d never really had that experience, to know that she was loved, lovable, her very nature is love, you know? Because she was wounded in that area, a wound is where we’re shut down out of some kind of pain or trauma around the area from love, of being seen. This is where the relationship comes into the picture. So, you could say all our psychological wounds are relational wounds, they are all in the area of love, not feeling seen, recognized, accepted, loved as we are. And so as she got in touch with the feeling that deep sense of disconnection from love…So as she stayed with it her heart actually started to open to herself. And then she starts to access the love, actually. And so this is just a very short example of how we start out with her being a victim, to being stuck in a victim trip and the victim identity. And then just unpacking it, taking it apart. There’s always the notion that there’s some intelligence here, there’s something here that needs to be discovered, there’s some part of yourself that you’re disconnected from.

But the symptom of this [problemless] wound is just a, a manifestation of our…it’s a sign post, that points us in that direction. So, the solution for her was to actually feel love for herself through feeling the sorrow and the sadness. That actually awakened her heart. In the Buddhist tradition, we often talk about that—the awakening of the heart as bodhicitta. And compassion. I think bodhicitta and compassion have all come out of that sense of really deeply feeling. Compassion means “feeling with”. Deeply feeling the pain of yourself and the world. And that actually is the doorway into true compassion.

Vince: That’s so interesting because in this example, the woman that you’ve been working with, she’s been practicing for 30 years. And one of the questions that comes up for me, often in my own practice too is, how come meditation doesn’t necessarily give me the tools to go into my feeling life, and go into some of these woundings, like you’re calling them. Why doesn’t it necessarily give me those tools? Why is it sometimes necessary?

John: It’s not designed for that.

Vince: Yeah. Could you say more about that? Because that’s such a… I think a lot of people assume that it is designed for that.

John: It’s designed for liberation. I think there are two main tracks of human development. One is what we can call, very simple terms, colloquial terms, “growing up” and “waking up”. Growing up is kind of becoming a mature, human person. A genuine, mature human person. A mensch, basically. Someone who’s really open to life and relationships and can function in that way. So, I think that’s the basis, really, for the next level of human development, which is about liberation, liberation from samsara. So one is becoming a full human person, the other is going beyond being a person altogether. Buddhism is not oriented toward becoming a person, particularly. But it’s about liberation from, conditioning, from karma, from the past, from ego, from the fixation on self. It’s about liberation from the fixation on self. That’s why it’s not going to take you in the direction of understanding the self more deeply, that’s the psychological work. That’s what I call horizontal work. It’s the process of unpacking what’s there in the psyche and clarifying it. Whereas I think meditation is more like what I would call vertical work. It’s more like cutting through, cutting through any state of mind to the essence. In Buddhist terms it might be called emptiness, or it might be called a pure awareness in some traditions. Or a non-dual awareness. Or Buddha mind, Buddha nature.

It’s about cutting through to that. That essence. That essence in fact does exist at the heart of whatever you’re working on. Psychologically or emotionally, it’s always there. But the meditative approach is to cut through to that essence, not to unpack the emotions, not to understand the emotions, not to work with the emotions and feel them more deeply and get to know yourself more deeply through connecting with your feelings—it’s not about that. It’s about liberation. It’s a really different trajectory of human development. But I think what’s important is both of those are important.

In other words, we’re both, human beings who are learning to become Buddhas. That’s one aspect. But also Buddhas waking up in human form and learning to be human. I think that latter part is not generally part of the Buddhist tradition. And it’s not emphasized in the Buddhist tradition. I think we need the whole cycle. Humans becoming Buddhas, Buddhas becoming humans. And then we have a complete circle.

Vince: Nice. And, I guess, just to play a little bit of devil’s advocate though…

John: Sure.

Vince: …I’m totally with you on this. I guess I could imagine someone who’s spent a lot of time practicing in the Buddhist tradition and really studying and, they could kind of point to different things and say, “Oh yeah you know the perfection’s or the paramis, and we’ve got all these sort of ethical conduct and…” These are all about becoming human or becoming more fully human.

John: Yeah.

Vince: But, and yet I hear that in some ways, the Buddhist tradition, is, in your opinion, has kind of fallen a bit short of that. So, how do you reconcile those two perspectives?

John: Well you know that was behind my whole work on relationships. You know I’ve written three books on conscious relationship, and I found for myself and was delighted to be introduced to Buddhism as a practice and so forth. And, of course, there are all the great teachings of compassion and the paramitas, generosity, loving-kindness and so forth…exertion and all that. And those are generally very valid and important to ethical principles, there’s no doubt about that. But how do you embody them, that’s the question. Because in our psyche we have the opposite going on most of the time, which is we’re confused, we’re grasping onto our faults. Constructed self is not such the real thing, and we’re defensive and we’re judgmental and [unintelligible]. So, how do you actually relate to those things? And so I think it often doesn’t help to take a principle like compassion and try to lay it on yourself.

Another example, I had a client who [was] part of a couple situation, and she had a tremendous amount of anger toward her husband, but she was Buddhist and she felt it was completely wrong for her to feel angry with her husband. And she, I think she had gone to one of her teachers who said, “Just let go of the anger and be compassionate.” Which is true as a general principle, it’s not to say that it isn’t a good general principle, it is a good general principle to be compassionate and to not get identified and caught up in anger and act that out, that’s very true. But in her particular case she was stuffing the anger, and she was using her Buddhist practice and her Buddhist teachings and her advice from her teacher to actually stuff the anger away and, therefore, she was not owning how she actually felt in the relationship. How she actually felt was angry. And I would say she had good reason to be angry from the way her husband was treating her, and if she wasn’t going to acknowledge that and bring that up to be worked with then, there was no way for her to actually make a move because she was stuck in denial and she was cut off from where she really was.

And so I think, it’s true, the general principle I’m certainly not arguing with, any of the general ethical, moral guidelines of Buddhism, I think they’re all great. But the question is the skillful means of how to actually…the compassion that might be needed in her situation would be compassion for her own anger, maybe that’s the first step. That the anger itself is there for a reason; again it has its own intelligence. And we need to hear from it, we need to hear what is there. And usually when you get in touch with something like anger there’s a lot more that comes with it, it’s not just anger. Its anger about being related to in a certain way and that has to be talked about honestly and openly. And I think it’s important for someone to be able to say, “I’m angry that X, Y or Z. You treat me this way; you act toward me this way X, Y, Z. And I’m angry about it.” Not to necessarily act it out in shouting and screaming, but to actually bring it to consciousness. And then it becomes integrated.

It’s like once you’ve cried—once you’re in sorrow—once you’ve cried, there’s a natural kind of letting go that happens. And I think when we really honor our feelings and go deeply into them and express the truth that is contained within them, then we can let them go. And then there’s a natural letting go, it’s not like I’m letting go because the teachings or principles say I should let go of anger. Because then if you’re falling in spiritual…this has been the problem, I think, with a lot of spirituality over the centuries, is that religion becomes a form of commandments or shoulds. I should be compassionate. I shouldn’t have anger. I should be generous. I should be devoted. That’s the right thing to be, but in fact inside myself, I don’t feel that way. And what do I do with that? Then I tend to stuff it, then I live a double life. That’s the setup for what I call spiritual bypassing. When you’re doing your spiritual trip but it’s not actually integrated into your actual psyche, and so it leads to lots of problems. It’s kind of a shadow problem, because of those things that are denied and stuffed away then start coming out in unconscious ways. And then we have all kinds of problems in sanghas and blow-ups and lack of communication. And even in our Buddhist sanghas I’d say the relationships, quality of relationships, is often not any better than it is in any other group and sometimes it’s a lot worse because we’re pretending to be more spiritual than we actually are in terms of how fully we’ve integrated that into our real life.

Vince: Wow, that’s a bombshell in some ways.

John: Yeah.

Vince: Ok, so given this perspective that you’re offering, that as Buddhist practitioners we don’t necessarily know how to embody some of this wisdom, this deep and personal wisdom.

John: Right, Right.

Vince: So given that Buddhist Geeks is probably much more of a group of meditators, than it is people that have been doing therapeutic work, are there certain things you’d say in terms of the specific skillful means, the specific practices or specific information for those type of people who may be listening to you and go “oh yeah, I think there is something to what he’s saying, and I really need to follow up on that.” Are there things you would share with those people, those meditators that would maybe support them in exploring the personal and doing some of this work that you’re talking about.

John: I’m coming to the place where I really feel like everyone who’s involved, and this is maybe not a 100%, but the majority of people who are involved in an Asian spiritual path, need to be also doing some psychological work. In order to integrate it, in order to be fully balanced in their practice and in their life. And ultimately, what I’d like to see would be that the Buddhist communities each have some way of processing emotional and psychological material, in small groups or one-on-one.

But, that doesn’t exist right now so I think that basically, we’d be useful for people if they feel they’re stuck in their lives and their practice isn’t addressing the places where they’re stuck, that, they should consider doing some psychological work. You know, finding a good therapist. I mean, it’s not easy to find a good therapist, I have to say. Ideally it’d be someone who’s got some kind of background in Buddhism. That would be compatible, and even more compatible. It doesn’t have to be that.

Vince: Nice, and have you found working with different mediators that when they start doing this type of work, what are the results often times for people? What’s the benefits of going into that?

John: Well I find for people who are sincere mediators—and that’s usually the kind of people who come to me, are very sincere about their practice. You have a leg up on the psychological work because you’ve already developed mindfulness. And you’ve already developed some commitment to truth. I find I love to work with people who are practitioners in that sense, because they actually move faster. And their mind is more developed. They’re sharper. They just need a little help and a little coaching to guide them in a slightly different direction, then they usually go.

So they’re actually taking the presence or the openness that you’ve developed on the zafu, and you’re actually now applying that openness and presence to the psychological material, to your feeling life, basically, or to your relational life. And you’re then allowing that to kind of reveal itself more fully, instead of just going toward pure awareness, or pure openness. In the psychological world I would call it applied openness, applied presence. It’s like applying in a very specific direction.

And usually, I have found that dharma students are my favorite clients because they have that leg up. They already have that commitment; they have that training, so it’s great. Occasionally, I mean this is rare actually for me but I’m not sure how common it would be overall, but occasionally, there are people who are threatened by…But they usually don’t come into see me, actually. I would say the people who are really threatened by doing psychotherapy are the people who need it the most. So if your listener is saying, “I wouldn’t go near that with a 10 foot pole,” [laughing] it’s probably a sign that you really need it. Actually there’s something down in your psyche that really, some part of yourself that you’ve given up on, you’re afraid of, that’s been shut down, shut off and denied.

And that there’s a tremendous fear about going there. If there’s a fear about going anywhere in your psyche then, that’s where you need to go, actually. Part of the path, the Buddhist path, is about fearlessness. And fearlessness is developed through confronting what we fear, actually meeting the fear directly. And so, that’s very much a part of psychological work. So I would encourage, consider doing that kind of work as a balance, and an adjunct to your spiritual work.