When I was a young child, I knew very little about the lines drawn by religions to set themselves apart. It all seemed one universe, one Divine Plan, as accessible as my hands & toes. I made bargains w/ the gods I thought ruled it all — bartering my behaviour for the crises common to childhood: a ribbon at the horse show, a win in the spelling bee. Even in Việt Nam, my belief in what started everything was fairly simple. Like a fish, I swam in the wide sea of my believing. I was 10 or 11 before I began to realise there were differences.

When I was a young child, I knew very little about the lines drawn by religions to set themselves apart. It all seemed one universe, one Divine Plan, as accessible as my hands & toes. I made bargains w/ the gods I thought ruled it all — bartering my behaviour for the crises common to childhood: a ribbon at the horse show, a win in the spelling bee. Even in Việt Nam, my belief in what started everything was fairly simple. Like a fish, I swam in the wide sea of my believing. I was 10 or 11 before I began to realise there were differences.

The first Buddhists I recognised as separate from my own life weren’t the monks who came daily, to the iron gate at the end of the drive. Chi Tám, our cook, would take out their morning alms of breakfast, bowing as she handed them rice in round blue & white bowls.  The monks, even robed in saffron as they were, didn’t seem a lot different than the frocked priests at Jeannie Adams’s Catholic catechism class, or the collared pastor at the ecumenical church we attended Sundays. Or even the rabbi at Sydney Maynard’s synagogue on Saturday service. After all, Aunt Lois was a 7th Day Adventist, and they kept Sabbath on Saturday. Already a child of a polycultural life, what people wore to serve divinity seemed pretty irrelevant to the child me. (Still does :).)

The monks, even robed in saffron as they were, didn’t seem a lot different than the frocked priests at Jeannie Adams’s Catholic catechism class, or the collared pastor at the ecumenical church we attended Sundays. Or even the rabbi at Sydney Maynard’s synagogue on Saturday service. After all, Aunt Lois was a 7th Day Adventist, and they kept Sabbath on Saturday. Already a child of a polycultural life, what people wore to serve divinity seemed pretty irrelevant to the child me. (Still does :).)

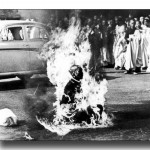

The first Buddhist I knew was not distinguished by his dress, or even his faith, but by his actions. He was completely different from any religious believer I had ever encountered. His name was Thích Quảng Đức (born Lâm Văn Tức), and he burned himself to death, just three blocks from our house.

I was young, but I heard about it anyway. We all did. And the idea that someone would burn himself up — quietly, w/ dignity and grace — in protest of the war my own father and his colleagues were enmeshed within… I couldn’t fathom it. This revered religious figure sat down in a circle of his friends and colleagues, and poured gasoline over himself. And then he put a match to it all…And he sat there, immobile, the bystanders said. While his body and his life went up in scarlet flame and thick black smoke

I was young, but I heard about it anyway. We all did. And the idea that someone would burn himself up — quietly, w/ dignity and grace — in protest of the war my own father and his colleagues were enmeshed within… I couldn’t fathom it. This revered religious figure sat down in a circle of his friends and colleagues, and poured gasoline over himself. And then he put a match to it all…And he sat there, immobile, the bystanders said. While his body and his life went up in scarlet flame and thick black smoke

The thought of Thích Quảng Đức’s conscious sacrifice ignited something inside of me — some tiny but similar flame that said war has to be wrong, if a man would do this, out of his faith. For peace.

Earlier encounters with Buddhism were far less dramatic, although equally profound. I’ve written elsewhere about the temple in the banyan tree, and later visits to temples in Bangkok, where I graduated from high school.

But Thích Nhất Hạnh has a special hold on me. For one, he’s Việtnamese. This has always been important to me. I spent almost 5 years of my childhood — formative years — in Saigon, and Thích Nhất Hạnhwas from the beginning a connection to that time and place. He also was anti-war, in the quietly powerful fashion of a monk who inherited the legacy of Thích Quảng Đức.

has always been important to me. I spent almost 5 years of my childhood — formative years — in Saigon, and Thích Nhất Hạnhwas from the beginning a connection to that time and place. He also was anti-war, in the quietly powerful fashion of a monk who inherited the legacy of Thích Quảng Đức.

Thích Nhất Hạnh’s also a gifted poet, something that became increasingly significant as I found my way into the craft and art of poetics. Poets see things differently, and to know that he too sees with the kaledeiscope eyes of the poet meant much as I learned my craft. When asked about his 39 years of exile from his home country of Việt Nam, he replies to Oprah: I was like a bee taken out of the beehive…

And finally, Thích Nhất Hạnh loves tea. Watch his face light up in this excerpt from the upcoming Oprah interview.

And finally, Thích Nhất Hạnh loves tea. Watch his face light up in this excerpt from the upcoming Oprah interview.

This Sunday you can watch Oprah’s complete interview with this very special man on OWN, Oprah’s TV network. It airs at11 a.m. Eastern Time.