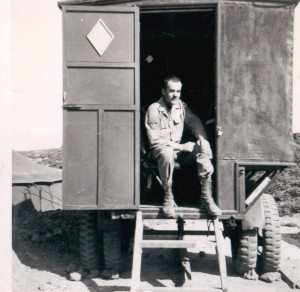

This is my father, who served in three wars: WWII, the Korean War — from when this was taken — and the Việt Nam Conflict. He served in multiple theatres (China, Korea, Việt Nam, the Battle of the Bulge, Germany, France, et al), sustaining several major injuries. When I was a little girl, I used to trace the deep scars on his calf, where a bullet entered and exited. He eventually retired as a light colonel (Lieutenant Colonel). Just this winter he was inducted into the Oklahoma Military Hall of Fame.

My 2nd sister also served, Việt Nam era, Army. A lifer, as we say, retiring as Staff Sergeant. My 3rd sister served in the Air Guard. My nephew was Army. My father-in-law Merchant Marine (which had the highest fatality rate in WWII). My husband was a Việt Nam DMZ Marine. Uncles and cousins served at Annapolis, at the Pentagon, overseas, and locally.

In other words? The military is a BIG part of my family culture and tradition. But I’m a pacifist by calling. That may seem incongruous, unless you consider what happens to those who serve: they often die. And then there are the fates far worse than a clean death: death on a battlefield, POW status, PTSD, major disability… All too often, our vets sacrifice far more than their lives.

The thing about the armed forces is that you always knew they would take care of you. You had GI bill, and GI benefits, and VA medical if you needed them. You had a VA loan for a house, and other benefits PROMISED you by the government, in return for which you often gave up your very sanity. Certainly in my family, we understand the devastating impact of PTSD. Not to mention fragmented families, dislocating moves, and the other challenges to military life.

PTSD wasn’t identified until Việt Nam’s vets began to manifest it in far more visible numbers than WWII’s taciturn veterans. Even though my beloved Aunt Bonnie would tell us how CD, her son, was never the same after his service on Iwo Jima, and in the Pacific theatre. And my father would tell me that all wars were the same: men died, and those who came home never forgot it. It’s been that way, Jonathan Shay reminds us, since Achilles & Odysseus.

PTSD wasn’t identified until Việt Nam’s vets began to manifest it in far more visible numbers than WWII’s taciturn veterans. Even though my beloved Aunt Bonnie would tell us how CD, her son, was never the same after his service on Iwo Jima, and in the Pacific theatre. And my father would tell me that all wars were the same: men died, and those who came home never forgot it. It’s been that way, Jonathan Shay reminds us, since Achilles & Odysseus.

This is all by way of saying that today’s 30 Days of Love directive involves connecting to those who serve(d). Not only honouring them with words, but with our welcome into our wisdom traditions, with care for the injuries they have sustained on our behalf. And with respectful recognition that they have been warriors — something not all traditions are comfortable with. That’s okay, because if you support our veterans, then you are verrry careful where you send them. Because many will DIE. And their families will suffer whether or not they return. That makes me a die-hard pacifist.

Next? You don’t mess with their benefits. You don’t cut pensions after folks have paid for them with their blood, limbs, and mental health. My sister depends on her pension. So do many millions of veterans. And when statistics show that 170,000 US veterans were cut off of their critically needed food stamps last November? You KNOW that’s wrong. So don’t support it, while you pretend you support veterans.

http://www.ivaw.org/

Nor do you support programs that reduce pensions, or services. Because real people (again, my sister, who spent 20 years in military, primarily as a divorced mother of two) are affected. And real lives depend on our remembering that veterans don’t always have jobs. Some can’t hold them. Estimates for homeless veterans are that 12% of all homeless are veterans. Many need counseling as well as other health benefits.

While teaching at Oklahoma State University, I used a wonderful anthology — the Norton Book of Modern War. It has always been important to me that America remember what’s involved when we go to war: the loss of real lives, the orphaning of children, the destruction of peace of mind — sometimes forever — for thousands of men & women. The anthology reminds us that war, as my father told me, doesn’t change in its essentials. It maims, kills, and ruins lives. Given how many young Americans served (and continue to serve) in foreign engagements, it’s imperative that we pay up our part of the bargain we made with them. And that we remember: taking care of our veterans after service is only a very small acknowledgement of what we owe. But it’s critical. These are the last Americans we should forget.