Inclusion is a big deal to me (I know — so many things are!). Perhaps because I grew up on the outside, often looking in. Maybe because my family is pretty polyvalent. And maybe because it IS important. Every voice needs to be acknowledged, listened to, and paid respect.

Inclusion is a big deal to me (I know — so many things are!). Perhaps because I grew up on the outside, often looking in. Maybe because my family is pretty polyvalent. And maybe because it IS important. Every voice needs to be acknowledged, listened to, and paid respect.

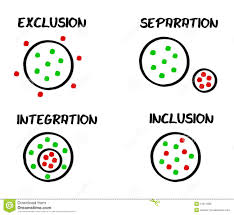

For whatever the reason, when I saw today’s prompt for 30 Days of Love, I could relate: how do we know when we’re included? What makes us FEEL included?

Despite my appearance now — nice middle-aged white woman of privilege 🙂 — I grew up odd kid out. White kid in Việt Nam, or Thailand; new kid over & over; white chick in the Middle East (where only the prostitutes looked like me 🙂 ). I didn’t fit in, and it was obvious. I’ve never forgotten. I actually left university — at least in part — because there wasn’t any literature by my friends: no black or brown or many women writers being taught. I love literature — and did then, as well — but where was Eldridge Cleaver (whom I had to find on my own), or Richard Wright? Where was Maude Meehan or May Sarton?

Then when I applied for my doctorate, there wasn’t a single woman teaching in my area of concentration. So I didn’t go at that time. It wasn’t until there was another woman that I applied. Why would I want to go somewhere no one looked like me? How could they possibly know my life? Get my work?

Next, in my graduate work, I was a ‘returning student.’ Re: older than the rest of the bunch. And when I found my ultimate university job, I wasn’t a ‘real’ academic: I directed a federal grant. Not tenure-track, but administrative and teaching. Never mainstream — always an outlier.

This is by way of saying that all my privileges don’t fix that I was often (and sometimes remain) ‘the other.’ As Virginia Woolf said, if it’s like this for me, I can’t imagine what it’s like for my cousin Sally, who now uses a walker. Or my cousin Jenny’s daughter, who is a mixed race child (0f astounding beauty). Or my daughter-in-law, who is a Mexican American female in a male-dominated field. Or a friend passed over because as a black man, he can’t ever be part of his organisation’s ‘good ol’ boy’ network. And what about other black men, whom we’ve opened fire on across the country? Or the aging? Or the ‘beneficiaries’ of ‘positive stereotypes’ (a horrible designation common in the experience of several of my friends from Asian American families). Or the neurologically atypical, as a colleague calls herself (she has Aspberger’s), or the deaf, or the blind, or…. or… or …?

This is by way of saying that all my privileges don’t fix that I was often (and sometimes remain) ‘the other.’ As Virginia Woolf said, if it’s like this for me, I can’t imagine what it’s like for my cousin Sally, who now uses a walker. Or my cousin Jenny’s daughter, who is a mixed race child (0f astounding beauty). Or my daughter-in-law, who is a Mexican American female in a male-dominated field. Or a friend passed over because as a black man, he can’t ever be part of his organisation’s ‘good ol’ boy’ network. And what about other black men, whom we’ve opened fire on across the country? Or the aging? Or the ‘beneficiaries’ of ‘positive stereotypes’ (a horrible designation common in the experience of several of my friends from Asian American families). Or the neurologically atypical, as a colleague calls herself (she has Aspberger’s), or the deaf, or the blind, or…. or… or …?

Here’s what inclusion is NOT: it’s not a bunch of white guys sitting around talking about race. All they know is white guys, pretty much. Unless they are pretty atypical — and I acknowledge the possibility — what can they see? And how much credibility do they have? Far less than my department had when I didn’t apply, because no one looked like me.

Inclusion also isn’t a bunch of men of any race trying to figure out women’s health. Really? SO much wrong with that picture. Nor is it rich people talking about how poor people ‘should’ be/ do/ act. Or those who have pretending they understand what it’s like to have very little.

Because inclusion is hard. It’s messy trying to move past your own experience. It’s hard for white people to see white privilege, and sometimes (my friends tell me) it’s hard for black and brown people to bother, yet again, trying to explain what is to them the obvious.

I’m never certain of the ‘right’ thing to say, when in inclusive groups. But I keep trying. I screw up often — it’s just what happens when a well-intentioned but sometimes clueless person tries to work with difficult topics. I’ve been known to stereotype (a dear friend can tell you chapter & verse about my faux pas thinking black women ‘must’ be politically liberal 🙂 ). I read as much as I can: race theory, queer theory, memoir and history and the news. I ask people — when I can — what I should do. I rely on my friends to keep me honest, and help me out when I’m an idiot. And mostly? I try to just remember that people are people: we love, we hurt, we hunger, we breathe. And pretty much the basics are just that: basic to each of us.

I’m never certain of the ‘right’ thing to say, when in inclusive groups. But I keep trying. I screw up often — it’s just what happens when a well-intentioned but sometimes clueless person tries to work with difficult topics. I’ve been known to stereotype (a dear friend can tell you chapter & verse about my faux pas thinking black women ‘must’ be politically liberal 🙂 ). I read as much as I can: race theory, queer theory, memoir and history and the news. I ask people — when I can — what I should do. I rely on my friends to keep me honest, and help me out when I’m an idiot. And mostly? I try to just remember that people are people: we love, we hurt, we hunger, we breathe. And pretty much the basics are just that: basic to each of us.

Real inclusion looks like that Super Bowl commercial that garnered so much controversy, folks. (What! America isn’t hetero WASP??) It’s colourful, it rides in a wheelchair or uses a cane sometimes, it speaks different languages, and it often has a different wisdom tradition. Or none at all. It has two daddies, or two mommies. Or neither. By definition, it doesn’t look me, or you. It looks like us, like America.

And like America, it can be incredibly beautiful.