I grew up overseas, which I’ve probably mentioned somewhere. The important thing to know about growing up overseas is that it marks you. The places you love aren’t (usually) places you can return to. And long years may go by between visits, if you ARE able to return. Given that I spent my childhood in places that have exploded in population, the quiet avenues and beaches of my childhood are now jammed with tuk-tuks (the newer name for what we called cyclos or sailors), traffic jams, cabanas, and tourists. Not to mention the millions of people who actually live there (6+ million in Bangkok, 7+ million in Saigon).

Growing up outside the US means I have very few friends from childhood. Almost none, really. It also accounts — in part — for why I’m so very close to my three sisters: they were (still are) my best friends. No matter where we moved, they were there. Not so my BFF from 3rd, or 4th, or 5th, or whatever grade. Either we moved or her family did, whoever ‘she’ was.

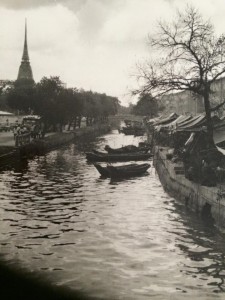

I have, however, reconnected w/ an old friend from high school. We worked on the literary magazine together, he as art editor, me as other editor. And just recently he posted a treasure trove of old photos to his FB page, photos Bill took with his Brownie camera during our lost childhoods.

This is Pattaya Beach, in Thailand. As it used to be, in the 1960s, when I was a young kid. By the time I was cutting school w/ my 2nd sister, and riding the military dependents bus down to the beach (about 45 minutes from school), most of it was more built up. But there were still spaces just like this. And the beaches on the way down south — to the villa where we spent summers, on an island now known for movie sets and a tsunami — looked like this for years after Pattaya ran pale with tourists.

I don’t take nearly enough pictures, although the advent of phone cameras has helped my lackadaisical attitude tremendously. Ironically, my first journalism job was as a photographer. I even had a darkroom, at one point. But when kids came, who had time for photography?? Even not working outside the home those first few years, my hours seemed filled w/ diapers, laundry, and baby/toddler play. A wonderful time, but not conducive to ‘spare time’!

Looking at my friend’s photos reminds me of so many things. Mostly that those early years in Buddhist countries shaped me in ways I could never have foreseen. That the every morning routine of monks coming to the house, in both cities, begging bowls in hand, became a saffron thread of what charity looks like. It’s not just a quarter in the offering plate; it’s food for real people, handed to them personally.

I’m very lucky, I realise, in the serendipitous arrival of my friend’s photos. Seeing my childhood through his Brownie camera’s lens, a kind of dreamy black&white version of an infinitely more complex time, I remember more than monks. I remember beginning to ask very hard questions: why the little girls on the street were begging. Why there were so many beggars. Why Americans didn’t ‘get’ the concept of face, and what that meant… Why, in other words, culture were so very very different.

There were questions, too, that surfaced not because I was an expat brat, although my outsider status made them more immediate, more pressing. Why, for instance, did we wage war in Cambodia? Why did we not help the Việtnamese refugees who flooded the US? Why didn’t we do something about the mixed race babies, sons & daughters of our GIs? These questions would ground my exploration of wisdom traditions. If the faith didn’t engage w/ these important issues, I wasn’t interested.

I still don’t have those answers, although I could soothe that little girl’s unease with her own difference. I could promise here that someday it would be better, and while she would never ‘fit in,’ she would be happy. And that an old friend was taking pictures so she could remember.