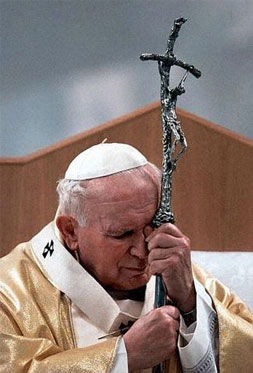

<!– –> Wednesday marks the third anniversary of the death of John Paul II, a passing that provoked such an enormous outpouring that the world—and even the College of Cardinals who gathered with the unenviable task of choosing his successor—was transfixed for weeks. We hardly need much prompting to remind us of the emotions and images of the “avvenimenti di Aprile”—the events of April—as Vatican officials, in their reflexively understated curial way, took to describing them. Almost immediately, crowds in the piazza beneath the late pope’s window started with chants of “Santo Subito,” calling for John Paul’s instant canonization. Many commentators dubbed him (as a few die-hards had for years before his death) John Paul the Great, conferring an honorific granted to just two other pontiffs, and none since the Dark Ages when Barbarian armies threatened the Eternal City.

–> Wednesday marks the third anniversary of the death of John Paul II, a passing that provoked such an enormous outpouring that the world—and even the College of Cardinals who gathered with the unenviable task of choosing his successor—was transfixed for weeks. We hardly need much prompting to remind us of the emotions and images of the “avvenimenti di Aprile”—the events of April—as Vatican officials, in their reflexively understated curial way, took to describing them. Almost immediately, crowds in the piazza beneath the late pope’s window started with chants of “Santo Subito,” calling for John Paul’s instant canonization. Many commentators dubbed him (as a few die-hards had for years before his death) John Paul the Great, conferring an honorific granted to just two other pontiffs, and none since the Dark Ages when Barbarian armies threatened the Eternal City.

This anniversary, coming in the run-up to Benedict’s own inaugural visit to the United States (during which he will mark his own 81st birthday, on April 16, and the third anniversary of his election, on April 19), would seem to shadow once again Benedict’s papacy, as John Paul’s legacy was perhaps bound to do. Many commentators lament that comparisons between the two popes, apparently unfavorable to Benedict, continue to be made. Yet such contrasts are inevitable, I think, and justifiable in that these are two different men, and should be judged on their own merits. Americans should also know what to expect of Benedict, so that they can better appreciate what he says (or does not say).

What I think too few stop to appreciate is that for all their notable differences, there is a great continuity between John Paul and Benedict in the amount of energy they bring to the papacy. Why is that the case?

Because of the length of John Paul’s pontificate (26 years, the third-longest in history) and the grandezza of his early years as pope—leaping the Berlin Wall, surviving a near-assassination in St. Peter’s Square, etc—it is often hard to remember that the last half of his pontificate was marked by illness and growing immobility. The man who chafed at being a prisoner of the Vatican spent much of his reign as a prisoner of his own body.

That he bore his sufferings with such dignity and even joy—ever the “Happy Warrior” of Longfellow’s poem, as George Weigel wrote in his biography of the pope—was as important to the acclaim and affection that accompanied his later years as the obvious heroism of his early years in Rome and abroad. Indeed, John Paul bore his condition with such grace that too few realize how difficult it was for him.

I was always struck by a story that John Paul told in a little-known 1982 biography by a French journalist, André Frossard, of the moment of his election as pontiff in 1978. John Paul told Frossard that at that instant, in the brief seconds before Karol Wojtyla became Pope John Paul II, he plunged his face in his hands at the gravity of what had befallen him, and his first thought was of his long-ago pastoral work as a priest in Poland working with bed-ridden patients, “those incurable invalids condemned to the wheelchair or chained to their sick bed; people who are often young and conscious of the implacable advance of their illness, prisoners in their sufferings for weeks, months or years.” John Paul found in the “terrible irreversibility” of their condition a parallel to his own new circumstances as pope.

Yet it was also a foretaste of his own physical decline decades later. None of us, I think it is safe to say, will ever know the drama—or trauma—of becoming pope. As the conclave vote swung inexorably toward Joseph Ratzinger in April 2005, the cardinal said he prayed not to be chosen. “As slowly the balloting showed me that, so to speak, the guillotine would fall on me, I got quite dizzy,” Benedict, told an audience of German pilgrims a few days after his election. Little wonder that the sacristy off the Sistine Chapel where a new pope is first vested is called the Sala della Lacrime, the Hall of Tears.

Yet the fear, or reality, of losing control to illness can seem a fate worse than death, and is all-too familiar for many of us. As John Paul grew more frail, he made many moving efforts to underscore the value of the elderly, and to encourage them by his example much as he invigorated the church with his energy in earlier years. “It is important to speak of suffering and death in a way that dispels fear,” he told hospice workers in Austria in 1998. In a letter addressed to the elderly for the 1999 World Day of the Sick, he described the achievements of the elderly Moses: “It was not in his youth but in his old age that, at the Lord’s command, he did mighty deeds on behalf of Israel,” he wrote. In August 2004, during a visit to the Marian shrine at Lourdes that commemorates miraculous healings. John Paul directly addressed his own condition in speaking to the ill: “With you I share a time of life marked by physical suffering, yet not for that reason any less fruitful in God’s wondrous plan.”

They are moving words. But it is how John Paul lived those words, in his “white martyrdom,” that makes them resonate. And in his own way, the octogenarian (but still vigorous) Benedict faces similar challenges, both because of his age and energy level, but also because of the papal legend he follows, and, in his own way, mirrors. Inspiring others while living within the limits of our temporal conditions is perhaps the greatest grace the elderly give to those who will inevitably come after them.