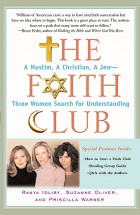

The author I interview today is famous AND one of us!! She co-authored the bestselling book, “The Faith Club” with Ranya Idliby and Suzanne Oliver. You may have heard of it: Ranya (a Muslim), Suzanne (a Christian), and Priscilla (a Jew) met with each other every week to come to a better understanding of each other’s faiths. (Visit The Faith Club website here.) Which is sort of what I do every time I have coffee with my (very lovable) sister-in-law. “Who am I talking to today?” I ask her. “Buddha, Mohammed, or Krisha?” Then I send her to Beliefnet’s Belief-O-Matic thingy so she can take the test and figure out what she is. Last time she came out as a neo-pagan. Then again, Catholicism was like number 23 for me.

I could not put down “The Faith Club,” which, as an OCDer was a problem, because I allotted myself four hours to read it. When I don’t make these deadlines, bad things supposedly happen. But I couldn’t help it. Every page a new issue popped up that was even more interesting than the last.

I especially laughed and nodded throughout the “Crucifixion crisis,” when Priscilla asks Suzanne if she’s heard the term “Christ killer.” Suzanne says no. I certainly have! I remember after my co-editor and I turned in “I Like Being Catholic,” one of my very sarcastic friends asked me what was next, “I Like Being a CK?”

It’s funny, even though I have more in common faith-wise with Suzanne, I identified most with Priscilla, because she’s very honest about her struggle with anxiety throughout the book: her panic attacks, her insecurities, her extreme guilt over situations other people blow off.

I found that especially comforting. Because she’s one of the people I would put into the “successful” category. And whenever someone “successful” confides in her readers about depression and anxiety, I think to myself, maybe it’s not so far out of reach for me, either.

So before I write a whole essay on why I’m thrilled to be interviewing Priscilla, and how loveable and vulnerable and honest she came across as in her book, I better get to my questions, so she can tell you herself, how she deals with a unique brain. UNIQUE!! That’s a good thing!

1) Okay, Priscilla. Sorry for that long introduction. I just was really moved by your book and by your bravery in confessing to the readers all of your insecurities. I found that so extremely comforting. I know how difficult that is, too. To use your real name and talk about these issues. You even give them a photograph of you on the cover! So someone, theoretically, could look at you in an airport and say, “Hey look! There’s the lady who has panic attacks!” Did you struggle with whether or not to expose your journey through anxiety? And are you glad you did?

First of all, no one recognizes me in airports. That might have something to do with the fact that I look nowhere near as good as I did over a year ago in my cover photo… I am aging with every passing moment. Also, it’s not like I’m Mariano Rivera or anything… (the famous Yankee pitcher my son spotted yesterday at our local movie theatre)

Initially, it wasn’t difficult to write about the most personal, embarrassing, painful aspects of my struggle with panic attacks, because I never really thought that the journals Ranya, Suzanne and I were keeping would ever be turned into a book, let alone a book read around the world. When we did finish the first draft of The Faith Club and an agent agreed to take us on, I freaked out. In fact, I panicked, cried, and lost a lot of sleep. I felt extremely exposed. I worried that people would see what I’d written and look right into my soul.

But I actually like that image now. The best thing a reader ever said to me was that I was both vulnerable and courageous at the same time. I cried when she told me that. It did feel like she was describing my essence and I was thrilled that I had somehow conveyed that to a stranger in the pages of our book.

I worried a bit when I knew The Faith Club would be published because I had never told my children about my battle with panic attacks. They probably had a clue their mother was a bit anxious, (you think?) but now I’ve given them some of the gory details. I do feel they’re old enough to read them. For a long time I was haunted by the idea that I might have passed my anxiety disorder down to my kids genetically, and that they would have to suffer as I did. But now I realize that I cannot shield them from pain and suffering. The best thing I can do is to admit my own frailties and display as much strength as I can.

I’m happy I didn’t edit myself to look like the “calm, serene Madonna” I used to tell my friends I longed to be. I like writing straight from my heart onto the page. I’m not a big self-editor when it comes to conversations (which is not always a good thing) and I don’t edit emotions too much when I write. That’s the kind of direct, honest writing I enjoy and it’s what I hope others like to read as well.

2) You write this:

For 35 years, I’d suffered from severe panic attacks. And after the events of September 11th, I was thrown into one long, never-ending state of low-grade panic.

Wow. Thirty-five years. You’ve got me beat (and trust me, that’s hard). How did you manage as an adolescent and young adult? How have you coped this long?

I think I finally just burned out, like those fireworks that trail off into the sky after elaborate bursts of explosions. My central nervous system was on high alert for decades, and it is still fragile if I don’t watch what I eat and drink. I try not to eat sugar (except for really dark chocolate.) I don’t drink caffeine or alcohol. I need regular exercise and sleep. After years of hearing my mother say, much to my irritation, “Just breathe,” I have found that she was right. Meditation, biofeedback in the form of deep breathing exercises and yoga really help me.

I was 15 when I suffered my first panic attack (although there was no name for the terrifying experience I had back then.) In fact, to this day I hate it when people say “I had a total panic attack” over things like a bad hair day. If you’ve ever had a true panic attack, you will never compare it to anything else in the world. I’ve had hundreds of them, and every one, in its own horrific way, made me feel I was crazy, out of control, mentally ill and/or dying. Hardly a bad day at the office or a wardrobe malfunction.

I had panic attacks at school, at work, on busses, planes and subways, while driving, in the middle of the night, at the beach…

After my first panic attack, a family doctor prescribed Librium, but it made me too sleepy. Then he gave me Valium, which I took as needed and carried with me everywhere. I self-medicated sometimes with alcohol. I started every day of college with a half a Valium, but never told a soul. I saw my first psychiatrist when I was 24 and have been in and out of therapy (mostly in) for decades.

I have felt like a “whackjob” (I love that you describe yourself that way – it’s so liberating!) for years. I thought I suffered alone, But ten years into my own private hell, I read a magazine article that finally used the word panic attack, along with agoraphobia. And it linked panic attacks to mitral valve prolapse, a common heart murmur, which I have. I was blown away to see my secret life talked about in black and white. Other people suffered like me.

Now I know there’s even an official medical term/diagnosis for what I have: Barlow’s Syndrome. After giving me an echocardiogram to check my heart murmur, a cardiologist told me about a man named Dr. Barlow, who was the first person to definitively links heart murmurs like mine with panic attacks. Just knowing that my symptoms had a name helped me to understand and own what happens to me: my valve doesn’t shut all the way, that sets off a rush of adrenaline, my “flight or fight response” kicks in, my heart pounds, my face flushes, my blood pressure rises, and I begin to hyperventilate, with shallow, rapid breathing, which makes me dizzy and weak and terrified. Understanding that physiological chain of events has helped. I am not crazy. My body chemistry and machinery is sometimes out of whack. (Hence whackjob.)

I’ve tried just talking myself out of a panic attack rationally. Sometimes that works, if I catch the symptoms early enough. It does help to calm me down. But to be honest, there’s nothing like good, effective medication.

Four years ago I found a psychiatrist who prescribed Clonopin for me. It’s helped me enormously. I take a small dose at night, and it stays in my bloodstream longer than Valium. I feel as though my internal clock was always operating a second too fast, and now it’s been set back a second, to what is probably “normal” for the billions of people on the planet who I once assumed were walking around in perfect mental health.

3) Your excerpts describing your guilt regarding your mother were especially poignant, and I know of many Beyond Blue readers who are going through exactly that. These paragraph are so powerful:

My 74-year-old mother, who had lived her life as a colorful, outspoken artist, had suffered two small strokes. Signs of dementia were evident, and doctors had determined that she could no longer live alone. …

I’d sat with my mother on her living room couch delivering difficult news quietly. I told my mother that we would have to find nursing care for her, that she could no longer drive or sleep alone in her house. “Do you want to talk about this?” I asked her gently. She shook her head, no. Giant tears rolled down her cheeks, but she remained silent, never one to confront her feelings head on.

My mother never told any of the doctors who examined her that she had a sister in California who suffered from Alzeimer’s disease, who’d been institutionalized years earlier. But she did tell me that I would be murdering her if I put her in a nursing home.

Even though the situation with your mom remains painful and raw, you seem to move to a place of acceptance towards the end. Maybe you feel a teeny-weeny, itsy-bitsy less guilty? Or am I just shoving a warm fuzzy into a crappy space? I guess, what I’m getting at, is this: do you have any wisdom to share with the other depressives who are in this same exact spot?

You asked me on a good day. I do feel less guilty…today.

A particularly rough period has ended. I had to move my mother to three different nursing homes in one year, before I finally got her into the best facility I could find. She had a very hard time adjusting to the last home. Although she has no idea where she is or why she’s there, she is finally at peace. And so I have a measure of peace now as well.

I did all I could to give my mother the life I think she would have wanted me to arrange for her, under tough circumstances. When she could no longer live at home, I made the best arrangements I could. I used to feel guilty about putting her in a nursing home, but every time I go back over the events that led me to do that, the eventual outcome seems inevitable.

I have cried for years about the death of my mother’s vibrant personality. She was the most colorful person I ever knew, a talented artist and complex individual. It was terrifying to see a woman who had been so vital, provocative and demanding all her life turn into a near-stranger: a docile, meek lady who attempts to play Bingo in a nursing home.

It is frightening to imagine that the same thing might happen to me someday. I talk to my children about what I would like them to do if I should be diagnosed with Alzheimers. That’s a pretty courageous thing to do and I give myself a pat on the back for doing it.

I would ask people to be kind to themselves. Learn from your mistakes but know that you are human and life is messy and mistakes get made. You can only do your best, and sometimes you might have to take what I call a “mental health day,” where you sleep, eat chocolate, watch cheesy reality tv shows and cry.

4) I cried at the part in your book where you explain your family history-all the “nervous breakdowns” among family members, time spent in mental institutions by relatives-and your constant fear that you would one day “go crazy” too and suffer a “nervous breakdown,” where you would disintegrate into madness. I so identified with that. My godmother, my aunt Mary Lou, was in and out of institutions her whole life. I was always scared-from as far back as I can remember-that I was like Mary Lou. And when she took her own life (I was 16), I was sure that a garage full of carbon monoxide would be my fate, as well.

I underlined every word on pages 102 and 103:

Despite my weak emotional constitution and panic attacks, I managed to build a good life for myself, with friends and boyfriends, academic and artistic successes. I met the love of my life and got married. I survived two pregnancies, despite several panic attacks, and gave birth to two wonderful, healthy sons. But I was a fraud. Nobody knew I was broken, that my body reared up and betrayed me on a regular basis.

I love that so much because that is the CLASSIC thought: I AM A FRAUD. I have a very successful friend, Michelle, the author of 75 percent of the letters in my self-esteem file. I couldn’t believe it when she told me she felt like a fraud. Because in my eyes, she had it all. She was this big-time editor with an incredible reputation. Her husband adores her. She has a fan club. And yet she told me that when she feels depressed, that is the first thing that pops into her mind: “I’m a fraud! My degree was by chance, really it was. All of my success is purely luck. But it’s going to end soon …. When everyone finds out the ugly truth.”

Are you better able to recognize this voice now that you know it’s part of the beast?

On a good day, when my creative juices are flowing and my hormones are cooperating, I don’t think I’m a fraud anymore.

Here’s why: I’ve had years of therapy. I have talked about the person I thought I was, I hoped I was, I feared I was. I have talked about the family I grew up in and how they influenced me. I have talked about where their lives ended and mine began, about the differences between us. About the random nature of life and “success.” About what I achieved on my own and what I was fortunate enough to have “happen” to me.

I have reflected on all of my talking and decided that everyone in life is successful. Some of us define goals and achieve them and call that success. Some of us stumble upon “success” by being in the right place at the right time, meeting the right person, making well-researched choices or guessing at decisions that turn out to be good ones.

Some of us don’t recognize that we are “successful” and some of us even think of ourselves as “frauds.”

Just before our book was published I spent time with friends on Martha’s Vineyard. I voiced my concerns and fears about The Faith Club’s launch, our upcoming media appearances and long book tour, which entailed lots of public speaking. Out of the blue, a woman I met briefly up there emailed me the following quotation one day and I am eternally grateful for her thoughtfulness and insight into my thought patterns. I found these words to be extremely helpful and liberating:

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, Who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small does not serve the world. There is nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won’t feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It’s not just in some of us; it’s in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we are liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.– Marianne Williamson

5) I also nodded when you said to Suzanna and Ranya that it was no wonder they never saw God as the one responsible for keeping the world in order because they never experienced the kind of frantic chaos within their bodies as you (and those who suffer from anxiety and depression) feel. “You’ve never longed for that order,” you said.

I think that those of us that struggle with anxiety and depression do demand more of God, but, in a way, don’t you also think that makes us more capable of seeing God in everything, too? It was evident to me while reading your book, that you saw God in so many places: in the beauty of the landscape as you looked out your window from your flight, in your son’s hoops at the basketball court, in your husband’s strong embrace, and even in the illness of your sister, and in the frustrating moments with your mother. You saw God in so many places, and I can’t help but think that maybe it’s because you are so aware of your fragility. Yes? No? Yes, no, yes, no, and then yes again?

Yes, yes, yes, yes, yes! You have read my mind as well as my writing!

I was sure for most of my life that I was cursed with this strange, scary central nervous system that could go haywire at any moment. I was defective. Why was I wired so differently than everyone else on the planet?

But now I thank God every day that I am wired to be so sensitive. I’m not embarrassed to be the kind of person whose emotions sometimes explode or overflow. Of course, I don’t necessarily want that to happen while I’m onstage talking to hundreds of strangers. There’s a time and place for everything.

But I would never want to be any other kind of a person. I am able to appreciate extraordinary joy because I know what it feels like to experience true grief and sorrow.

Many of the people in my family are creative and I thank God that I am able to express strong emotions through writing and art. I have a huge palette of colors to work with. I feel blessed to be able to experience life with such a wide range of emotions.

6) I also underlined every word in your chapter on prayer. I was fascinated that a Jew and a Catholic had so many common thoughts about prayer-especially when you were young. Priscilla, I could have written your paragraph, word for word, explaining how you said your prayers as a teenager:

I kept a mental tally of the difficulties I’d faced (few) and the advantages and blessings I’d received (many). I figured that keeping this kind of tally would bring me good luck, or ingratiate me with God. If I appreciated the life I had, the way my blessings outweighed my difficulties, then life and the people I loved could not be cruelly snatched away from me-by anyone, including God. If I were constantly vigilant, aware of how high the stakes were, how much I would miss the blessings I’d been given, then maybe I could hold onto them.

I always thought my scrupulosity or whatever you call it had everything to do with being Catholic. But then here you come, a Jew, and you’ve had exactly the same thought process as I have. So maybe it’s more neurosis than piety? Yikes. And I thought I was so holy! What do you think, and has your mind relaxed any? Does it get better after inhaling large quantities of chocolate?

A lot of what I expressed in that writing still resonates with me. I am not ashamed that I was obsessed with the advantages and blessings I had received back then. Who wouldn’t be, in my shoes? I have been enormously blessed with what has sometimes seemed an embarrassment of riches.

What has changed is that I don’t still have the ego-centric notion that I have some sort of GPS system attached to me, that God is watching over Priscilla Warner every minute of every day. How crazy is that? I am a speck, to quote my friend Angela and Richard Lewis, the comedian. I am now comfortable knowing the obvious – that I am not in total control of my life.

I have embraced humility. Big-time.

Ranya taught me that Islam means “to submit,” and I have submitted. I say that I have shrunk myself down, like Alice in Wonderland did when she drank the potion that made her small. I have acknowledged my tiny place in the vastness of the universe. And instead of feeling scared, lonely and insignificant, I feel free. I feel connected to the world in an exciting new way. I like the view from down here. I’m a drop in the ocean of human suffering, pain and joy. The problems that used to collide around in my brain, thundering loudly, have shrunk along with my ego. They are now simply my share of the enormous pain and suffering which the entire world must endure. And the joy I feel is much larger than life, much more potent than anything I ever felt before I “shrank myself down.”