I’m sorry to report that I don’t have an interview today. But I DO have some fodder for a great discussion. Beliefnet’s Lilit Marcus directed me to Newsweek’s psychology story “Happiness: Enough Already” about the “anti-happiness” movement, or shall we say the “appreciation of melancholy” backlash to the positive psychology, Now-Everyone-Wear-Your-Smiley-Face trend that has made the covers of too many bestsellers and been the topic of way too many Oprah episodes in my very humble (and smiley face) opinion.

I found Newseek’s article fascinating but a tad disturbing.

While I appreciate the thrust of the piece—and can see why psychologists and others feel compelled to swing that pendulum the other way (to melancholy)—that still doesn’t do anything for the depressive. One side sees us as a bunch of lazy bones who haven’t shot our happy face into the universe with its intention of gratitude and waited for it to reproduce. The other side? Blessed are the sad! That means you just have so much more to give the world! Oh, it’s good to cry. Oh yes it is.

I know that according to both sides it seems that Americans pop pills way too prematurely. But here’s the thing: I see a lot of people in my life who SHOULD be popping pills, but don’t because of articles like this: It’s normal to be sad. It’s good to be sad. Let’s not jump to a diagnosis. And in those two years, as a person is grieving or processing or whatever, her family members pick up all the responsibilities. Now how fair is that to them? Maybe it would be too quick for her to take a few Zoloft tablets … but if that alleviates everyone’s stress—and allows both she and her family to be more productive–then why not use the band-aid?

Yes, many sores heal on their own. But many get infected over and over again because the proud guy won’t accept the dang band-aid.

As a depressive, I, of course, don’t think that Sharon Begley, the Newsweek writer, made a clear enough distinction between what is healthy sadness and what is crippling depression—because that area is so very vague and needs handled oh so delicately. She sort of tosses those categories around as if she were an Italian chef preparing the crust of a pizza. Up it goes!

Here’s the essence of the piece. If you aren’t able to read the entire article you can get to by clicking here:

[Eric] Wilson argues that only by experiencing sadness can we experience the fullness of the human condition. While careful not to extol depression—which is marked not only by chronic sadness but also by apathy, lethargy and an increased risk of suicide—he praises melancholia for generating “a turbulence of heart that results in an active questioning of the status quo, a perpetual longing to create new ways of being and seeing.”

I don’t like the way that line is squeezed in there–“while careful not to extol depression, etc.”–because it sort of sounds like all the qualifiers that come after a radio ad. You know what I’m talking about. Um. What the heck did you just say? “Ask you doctor about it … various-side-effects-are-possible-like-heart-attack-stroke-chesthair-bloody-urine-and-herpes.” She does get to this later (as you’ll see a few paragraphs down), but never really takes the diagnosis of major depression all that seriously. Because, like the little boy in “Sixth Sense” I have seen dead people, I do.

Begley writes:

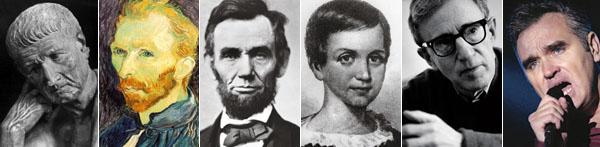

Abraham Lincoln was not hobbled by his dark moods bordering on depression, and Beethoven composed his later works in a melancholic funk. Vincent van Gogh, Emily Dickinson and other artistic geniuses saw the world through a glass darkly. The creator of “Peanuts,” Charles M. Schulz, was known for his gloom, while Woody Allen plumbs existential melancholia for his films, and Patti Smith and Fiona Apple do so for their music.

I’d love her to interview Peter Kramer, author of “Against Depression” on this very issue, because what he says is also valid: “Do we know what these people would have been capable of had they taken some Prozac? Maybe even more.”

Kramer was interviewed by the editors of “The Johns Hopkins White Papers.” His perspective on the cultural influences on depression is enlightening and compassionate. Per the “White Papers”:

Kramer believes society’s complicated view of suffering equates depression with intelligence and depth. Despite the reality that sufferers often face rejection and a lack of empathy, he writes, “there is an attitude I call “faute de mieux”—when we cannot alter a misfortune, we may attribute value to it, for lack of anything better to do.” This interferes with recognition of depression as a devastating illness without redemptive qualities.

Kramer thinks that this confusion is true of “any affliction that is romanticized and stigmatized Mental illness has forever been held up as stigmata, as having a spiritual quality, yet also a spiritual weakness or inadequacy.” He asserts that these moral and aesthetic overtones will disappear when depression becomes thought of as a more routine disease. This has happened with formerly idealized conditions such as tuberculosis.

To Kramer, a lingering bias exists in Western culture that values alienation and despair as aesthetic ideals. He traces the roots of this fascination back to the Greek cult of “heroic melancholy” that was seen as a trait common to great warriors. This elevation of melancholy’s status eventually evolved into the artistic idealization of despair as getting to the bleak “truth” about human existence.

Kramer argues that those types of underlying cultural assumptions—that dark characters and themes equate depth, and that lustful, joyful art is somehow inferior—influence his own patients’ doubts about the desirability of complete freedom from their symptoms.

I didn’t take medication for a very long time because I thought it would zap my creativity (for writing very dark, bad poems about a lonely hole that couldn’t find filling—wouldn’t Freud have had a field day with that one). I think many depressives have the same fear. But one of my many psychiatrists—the one who fed me a new cocktail every time I arrived—did have a good point when he said: “The creativity doesn’t go away. Some of the disabling pain does. So not only will you be able to write. You’ll write stronger, more eloquent prose” (or poetry, if I wished to go back and try to fill the hole).

He was right. My best writing has happened under the care of a very good doctor (which wasn’t him).

Here’s the guts of the Newsweek article:

That may be the most damaging legacy of the happiness industry: the message that all sadness is a disease. As NYU’s Wakefield and Allan Horwitz of Rutgers University point out in “The Loss of Sadness,” this message has its roots in the bible of mental illness, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders. Its definition of a “major depressive episode” is remarkably broad. You must experience five not-uncommon symptoms, such as insomnia, difficulty concentrating and feeling sad or empty, for two weeks; the symptoms must cause distress or impairment, and they cannot be due to the death of a loved one. Anyone meeting these criteria is supposed to be treated.

Yet by these criteria, any number of reactions to devastating events qualify as pathological. Such as? For three weeks a woman feels sad and empty, unable to generate any interest in her job or usual activities, after her lover of five years breaks off their relationship; she has little appetite, lies awake at night and cannot concentrate during the day. Or a man’s only daughter is suffering from a potentially fatal blood disorder; for weeks he is consumed by despair, cannot sleep or concentrate, feels tired and uninterested in his usual activities.

Horwitz and Wakefield do not contend that the spurned lover or the tormented father should be left to suffer. Both deserve, and would likely benefit from, empathic counseling. But their symptoms “are neither abnormal nor inappropriate in light of their” situations, the authors write. The DSM definition of depression “mistakenly encompasses some normal emotional reactions,” due to its failure to take into account the context or trigger for sadness.

That has consequences. When someone is appropriately sad, friends and colleagues offer support and sympathy. But by labeling appropriate sadness pathological, “we have attached a stigma to being sad,” says Wakefield, “with the result that depression tends to elicit hostility and rejection” with an undercurrent of ” ‘Get over it; take a pill.’ The normal range of human emotion is not being tolerated.” And insisting that sadness requires treatment may interfere with the natural healing process. “We don’t know how drugs react with normal sadness and its functions, such as reconstituting your life out of the pain,” says Wakefield.

Even the psychiatrist who oversaw the current DSM expresses doubts about the medicalizing of sadness. “To be human means to naturally react with feelings of sadness to negative events in one’s life,” writes Robert Spitzer of the New York State Psychiatric Institute in a foreword to “The Loss of Sadness.” That would be unremarkable if it didn’t run completely counter to the message of the happiness brigades. It would be foolish to underestimate the power and tenacity of the happiness cheerleaders. But maybe, just maybe, the single-minded pursuit of happiness as an end in itself, rather than as a consequence of a meaningful life, has finally run its course.

While I appreciate the fact that many people are given drugs prematurely—that some person do just need to process a loss or an emotion—there are so many people who wait WAY TOO LONG because of this very stigma. Why use words that “we have attached a stigma to being sad”? Shouldn’t we start with trying to GET RID of the stigma? To benefit both those that do suffer from major mood disorders AND those who may need two years to grieve a loss?

I like the idea that people are starting to say “What is up with all the dang smiley faces? Annoying!” But I don’t like more people saying that it’s not okay to be diagnosed with depression and use medication to treat it. No. That, for me, is a dangerous game, possibly even more dangerous than those Oprah smiley faces.