According to yesterday’s comprehensive article in the “New York Times” by Sarah Kershaw, this month the House has passed a bill that would require insurance companies to provide mental health insurance parity.

HALLELUIA! HALLELUIA! HALLELUIA!

Writes Kershaw:

It was the first time it has approved a proposal so substantial.

The bill would ban insurance companies from setting lower limits on treatment for mental health problems than on treatment for physical problems, including doctor visits and hospital stays. It would also disallow higher co-payments. The insurance industry is up in arms, as are others who envision sharply higher premiums and a free-for-all over claims for coverage of things like jet lag and caffeine addiction.

Parity raises all sorts of tricky questions. Is an ailment a legitimate disease if you can’t test for it? A culture tells the doctor the patient has strep throat. But if a patient says, ‘‘Doctor, I feel hopeless,’’ is that enough to justify a diagnosis of depression and health benefits to pay for treatment? How many therapy sessions are enough? If mental illness never ends, which is typically the case, how do you set a standard for coverage equal to that for physical ailments, many of which do end?

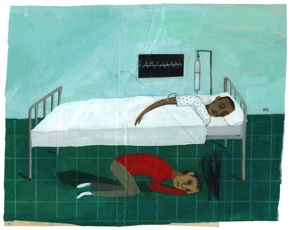

I suppose I might be a tad more excited about this than the average person because Eric and I spent $30,000 in mental-health fees during the fiscal year of 2006: two hospital stays that were supposed to be covered but weren’t, thousands of dollars in therapy because after eight sessions I hadn’t been cured, medication, and of course our $12,000 premiums for a year, since Eric works for a small firm, where he is one of the youngest architects and (surprise!) some of them aren’t in perfect health.

I’m pumped by this bill, not because I’m expecting my next counseling session to be covered. But because more than a few people might actually BELIEVE me when I say that I suffer from a brain disease commonly known as bipolar disorder.

After reading many of the comments on the combox of my post, “J.K. Rowling’s Suicidal Days,” I was convinced that day would never come, or if it did, it would be a century after scientists solved the whole global warming crisis and pollution problem.

Take a peak at those comments and you’ll see that we haven’t come all that far in our perception of mental illness. Most of the country—unlike Scandinavian countries where people treat mental illnesses as medical diseases—still says (or definitely THINKS) things like, “yikes, one of those pathetic sad cases who can’t get over her childhood crap”; the average American (in my circles, anyway) tells a person who accurately names her bipolar disorder as a brain disease that she is buying into the very flawed “disease model,” that by saying she “suffers from depression” she is cursing herself with a term renowned medical intuitive Caroline Myss calls “woundology”: defining ourselves by our wounds, and in so doing burdening and losing our physical and spiritual energy, opening ourselves to the risk of illness.

Yep, folks. That’s what we’re up against. And also these people, explains Kershaw:

Critics of parity say that anything that would not turn up in an autopsy, as in depression or agoraphobia, cannot be equated with physical illness, either in the pages of a medical text or on an insurance claim. These critics also say that because the mental abnormality research is so new, it should still be considered theory rather than an established basis for equal payment and treatment. “Schizophrenia and depression refer to behavior, not to cellular abnormalities,” said Jeffrey A. Schaler, a psychologist and an assistant professor of justice, law and society at American University in Washington. “So what constitutes medicine? Is it what anybody says is medicine? Is it acupuncture? Is it homeopathy?”

The Bush administration and other opponents say the list of disorders is far too broad. That leads from parity to another, parallel morass in the fields of psychiatry and pharmacology. Both fields are accused of over-diagnosis and of seizing on fashionable diagnoses — bipolar disorder or post-traumatic stress disorder, for example — for financial gain or through highly subjective assessments.

“It’s the phone-book approach of possible conditions,” said Karen Ignagni, president of America’s Health Insurance Plans, an industry group representing insurance companies that cover 200 million Americans. “And this comes at a time when advocates have made a very persuasive case about the importance of covering behavioral health.”

I’m wondering if any of Karen’s siblings have taken their own lives, or been so crippled by depression that they’ve had to drop out of school. My guess is no. Here’s the defense, thank God:

“Insurance companies balk at this, but there are striking similarities between mental and physical diseases,” said George Graham, the A.C. Reid professor of philosophy at Wake Forest University. “There is suffering, there is a lacking of skills, a quality of life tragically reduced, the need for help. You have to develop a conception of mental health that focuses on the similarities, respects the differences but does not allow the differences to produce radically disparate and inequitable forms of treatment.”

Attitudes about mental illnesses and addiction have changed significantly in the decades since advocates for the mentally ill — and for parity — first tried to include broad coverage of mental illnesses in the nation’s insurance plans. Pop culture has normalized and even glamorized rehab and even suicide attempts, chipping away slowly at social stigmas and lending strength to the idea that the sufferer of a mental illness or addiction may be a victim, rather than a perpetrator. Still, a cancer patient generally remains a far more sympathetic figure than a cocaine addict or a schizophrenic.

But scientific advances may go a long way to help the parity cause. The biological and neurological connection lends strength to the notion that mental illnesses are as real and as urgent as physical illnesses and that there may, at long last, even be a cure in this lifetime, or the next.

“The more research that is done, the more the science convinces us that there is simply no reason to separate mental disorders from any other medical disorder,” said Thomas R. Insel, director of the National Institute of Mental Health, which has conducted a series of studies on the connection between depression and brain circuitry and on Thursday released an important study showing a connection between genetics and the ability to predict the risk for schizophrenia.

Ever since I signed the contract to write Beyond Blue, I’ve buried my head in research that asserts the biological cause of depression because I have so many people tell me that I’m making all of it up. I don’t think any statistics that I share with some of them will convince them that mental disorders really aren’t imaginary friends, the kind we play with in the bath tub. I’ll always be part of what Caroline Myss calls the “wounded,” licking my sores and delighting in the taste of them. HOWEVER, for those who might try to open their minds to view depression and all mental illness with the same legitimacy as diabetes, cancer, and arthritis, here is my summary of my research, a piece I call “Depression Is a Brain Disease” 101:

Depression and bipolar disorder are more than imbalances of neurotransmitters (serotonin, norepinephrine, and dopamine), chemicals that bridge the synaptic clefts and pass messages to each other. These diseases are the result of organic changes in specific areas of the brain, especially in the limbic system, a ring of structures that form the brain’s emotional center, including the cerebral cortex, thalamus, hypothalamus, and hippocampus.

In his book Against Depression, Dr. Peter D. Kramer, Professor of Psychiatry at Brown University, provides an overview of research studies that sketch out the effect of stress hormones in the prefrontal cortex of the brain. Based on a survey of cutting-edge medical research, he believes that it’s the devastation in the amygdala and hippocampus regions–the significant cell death and shrinkage, and the diminished capacity for nerve generation–that contributes to fragile moods. “The longer the episode [of depression],” he writes, “the greater the anatomical disorder. To work with depression is to combat a disease that harms patients’ nerve pathways day by day.”

Kramer is trying to use his synthesis of research to change attitudes among psychiatrists and patients.

“Psychiatrists have learned that depression is progressive, and there is widespread agreement that we need to interrupt it very promptly and decisively to prevent further deterioration,” he writes. From a public health perspective, he believes that “depression is the most devastating disease known to mankind.”

There are psychiatrists and neurologists like Helen S. Mayberg, M.D., Professor of Psychiatry and Neurology at Emory University School of Medicine in Atlanta, Georgia, who are using brain-mapping techniques to view brain activity and how those functions affect our emotions.

“Thanks to refinements in brain-imaging technologies (higher resolution in PET scans and MRIs), scientists now know that there are regional patterns of brain activity–differences in specific circuits of the brain–that distinguish depressed people from non-depressed people,” she writes in an in-depth report in the October 2006 issue of The Johns Hopkins Depression and Anxiety Bulletin.

Mayberg sees this neurological perspective–focusing on specific brain circuits–as a new way of understanding depression, which coupled with a biochemical approach, can lead to more targeted treatments.

The research into the genetics of mood disorders continues to pinpoint the genes that may predispose individuals and families to depression and bipolar disorder. There has been remarkable success in locating and identifying genes associated with schizophrenia, and, more recently, with obsessive-compulsive disorder (the “transporter” gene SLC1A1). Researchers have confirmed a role for the gene G72/G30, located on chromosome 13q, in some families with bipolar disorder, and also evidence for genes on chromosome 18q.

Most recently, with genetic studies on families with major depression disorder, psychiatric geneticists like James Potash, M.D. have been able to mark a narrow area on chromosome 15 as having a tie to depression. In an interview with “BrainWise” the newsletter of Johns Hopkins Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences, Potash says this:Of nine genes in that vicinity that we analyzed, one, NTRK3, piqued our interest. We’ve just launched a study about 2,000 times more powerful than the last to make the suspect genes far more obvious, one that should clarify what NTRK3 and others are doing. For the first time, we have the potential to understand the truth about what sets depression in motion.

Moreover, researchers are beginning to see what a genetic predisposition to depression actually looks like. For example, the National Institute of Mental Health conducted a compelling study involving a gene known as the “serotonin transporter gene.” Further studies will point to biochemical pathways of disease and could lead to development of new medications to alter those pathways.

But even as all the genetic and structural information is interesting and helpful, the far more convincing data for the biological basis of mental illness, according to my psychiatrist and other doctors, is the natural history of these diseases.

“It didn’t take us finding the cellular basis of HIV or cancer or tuberculosis to convince us that these were diseases,” Dr. Smith explained to me recently. “It was the stereotypical nature of their symptoms and natural history.” So why should it take fancy science to convince people that mental illnesses are biological diseases?

Interestingly enough, 100 years ago tuberculosis was perceived similarly to depression today. It was an illness that “signified refinement,” Peter Kramer explains, containing a “measure of erotic appeal.” But that diminished as science helped identify the origins of the illness and as treatment became possible and then routine. “Depression may follow the same path,” writes Kramer. “As it does, we may find that heroic melancholy is no more.”

Even if depressives aren’t as fascinated by the biological basis of their condition, as I am, they should know this: Depression is an organic brain disorder. As Kramer succinctly states, “Depression is not a perspective. It is a disease.” End of story.