“You must do that which you think you cannot do.”

Those are words by Eleanor Roosevelt.

I remember the first time I read them.

David was about four years old, sitting in a level-eight karate pose as his instructor, a black belt in Tae Kwon Do, was telling the group of small boys that they must control their mouths, bodies, and minds. I was in the midst of one of my more severe panic attacks, trying like hell to stabilize my breath and think about everything I had to be grateful for as Katherine, two years old, was busy filling paper Dixie cups with water from the water cooler and dumping them into the trash. After getting the “get it together lady” glare from a few of the other karate moms, I picked up Katherine and walked to the restroom. I was shaking with anxiety at this point, and crying. I couldn’t hold back the tears anymore.

On the way to my secret hideout in the bathroom stall, I saw a framed print with the word DETERMINATION stretched across the top. There was an image of runners crossing the finish line with Eleanor’s quote: “You must do that which you think you cannot do.”

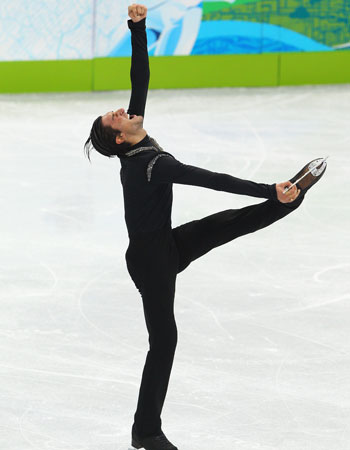

I suppose an Olympic athlete tells himself that daily throughout his training. He must go beyond his threshold, beyond any of his calculations. As I watched ice-skater Evan Lysacek and snowboarder Shawn White this year in Vancouver, I was inspired and awed by their courage, strength and perseverance.

It’s the same dogged determination that those of us with mood disorders use to get through our bad days.

Some might disagree, but I believe that getting through the ugly moments of a disabling illness–and especially a serious mood disorder that has your limbic system (the brain’s emotional center) shrink wrapped in pain–takes the stamina and fortitude of an Olympic athlete.

So does getting through a life chock-full of tragedy and heartache, like Eleanor Roosevelt’s. For starters, she lost her mom at age eight to diphtheria, an illness that claimed the life of her brother, as well. Two years later, the young Eleanor lost her dad, an alcoholic confined to a sanitarium, and as a young mother, she lost her third child, Franklin, as an infant. Her husband (Franklin) had an affair with a woman that Eleanor hired, and her mother-in-law was extremely overbearing and downright cruel to her at times. All that fun plus she was caretaker to Franklin when he became ill with polio.

In short, the woman was a saint. She was a living testimony to her mantra: “You must do that which you think you cannot do.”

Unlike the Olympic athletes, I have no dream of obtaining a tangible goal–of holding with five fingers a medal or Pulitzer Prize or New York Times bestseller or any kind of an evaluation that says I have arrived and need not feel insecure anymore. I’ve said this before, and I know it sounds morose to some ears, but my only intention here on Earth is to simply get to the finish line in a somewhat recognizable condition … to not truncate my life by a few decades because I’ve run out of hope … and to hopefully help a few other people on the way. But that requires the same type of training that the athletes undergo. I must constantly and consistently do the thing I think I cannot do.

* Click here to subscribe to Beyond Blue and click here to follow Therese on Twitter and click here to join Group Beyond Blue, a depression support group. Now stop clicking.