Anxiety arrives much like a surprise visit from an unwanted guest. You can be sailing along in your recovery program, doing all the right things, and then, BAM! You feel like you need to grab the paper bag you used to breathe through during your more severe panic attacks.

Anxiety arrives much like a surprise visit from an unwanted guest. You can be sailing along in your recovery program, doing all the right things, and then, BAM! You feel like you need to grab the paper bag you used to breathe through during your more severe panic attacks.

Interestingly enough, when I was in South Bend, Indiana a week ago visiting my alma mater, Saint Mary’s College, I had the pleasure of meeting with Dr. Catherine Pittman, a psychology professor and the author of a very helpful book (with Elizabeth Karle), “Extinguishing Anxiety: Whole Brian Strategies to Relieve Fear and Stress.” I placed it on the top of my other books to review and compose interview questions. But a few days after returning, I experienced the same heart palpitations and knot in my stomach that I recognize as acute anxiety.

I grabbed her book and have underlined practically every word of it. It’s full of great exercises to reduce anxiety. Since I’m presently in a major bout of it myself, I thought I’d feature some of her suggestions in a series of posts on “extinguishing anxiety.”

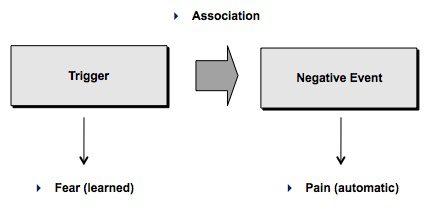

Today I wanted to explain her exercise of identifying your triggers, because this is an appropriate first step. Pittman clarifies the process of “association” that occurs when we experience those first symptoms of anxiety: shortened breath, heart palpitations, sweat, dizziness, nausea. Our brain (or more specifically, the amygdala or “fear center” of our brain) is pairing a trigger with a negative event from the past. The negative event produces an automatic pain or discomfort that we can’t really control. The trigger produces a “learned” fear or anxiety, that we can “unlearn” via replacing with new experiences. Here is the illustration she uses that I think is very useful to seeing how this occurs on an unconscious level.

Pittman explains how we can control our anxiety if we can learn to speak the “language of the amygdala.” For example, say you were bit badly by a pit bull (I know I will hear from readers with pit bulls, so I apologize in advance for using this dog as an example, but to be perfectly honest, they scare the bejeezus out of me) a year ago. You have developed a fear of pit bulls. So when you hear your neighbor’s pit bull bark, you tense up and feel anxious. His bark (the trigger) is associated with the negative event (bite). Since your amygdala has a killer memory, it automatically pairs the pain of the dog bite with the barking, so that you experience a kind of learned anxiety.

Merely seeing the simple illustration of how this works was helpful for me, because I realized the anxiety I am feeling today is produced by a few triggers I wasn’t even conscious of until I did Pittman’s exercise of identifying triggers that might be producing anxiety for me.

One was Memorial Day. On a subconscious level, I associate the beginning of summer with anxiety, because I tend to relapse in the summer, and during the summer of 2005 and 2006, I experienced the most acute anxiety and depression of my two-year slump.

The second was hanging out at the pool yesterday. The pool is a setting (and settings, alone, can act as a trigger, says Pittman) that creates some anxiety for me since, again, during that time of severe depression I remember not being able to contain my tears there, and wishing that I could find a way to drowned myself in the water. So, today, when I look at the pool, my subconscious memory says, “Remember those summers that you wanted so badly to die? You are going to feel like that again this summer.” I ran into a woman whom I saw frequently during that depressed time, so that reinforced the memory of those painful summer months. I began to exhibit physical symptoms. I tensed up. My shoulders rose. I clenched my jaws. And I had no interest in touching the free hotdogs and burgers that were being served because my stomach was knotted up.

The third (ongoing) trigger is the release and letting go of a project in which I poured myself into … the Commencement address. It’s natural to come down after you finish writing a book, or painting a room, or even finishing a scrapbook, to experience a sense of loss. Some projects absorb so much of your time and attention that, when they are over, you have an uncomfortable vacancy that creates anxiety. It’s a little like participating in an intensive program or retreat, when you bond with all the other participants. When you go home, the first days are tough, because you miss them. You have grown to enjoy them, and the letting go process can be a tad painful, especially if you have abandonment issues from your childhood. “I’m never investing my heart in anything again,” your amygdala might whisper in your ear.

So the way out of your anxiety, says Pittman, is to build new associations. For example, I have been concentrating on moments in the last few summers that I have been genuinely happy: at the kids’ swim meets, where I get to disqualify all the breaststrokers who are trying to get away with scissor kicks. I love playing cop! (Sarcasm here.) Especially to seven-year-olds trying to swim one length of a pool for the first time. In all seriousness, swim meets are a positive association for me, because I have memories that span ten summers or more from my youth, when I participated on swim team, and had a blast with fellow teammates. They were a source of great joy. And so I try to go back there, and replace the summers of depression, with new swim team memories of coaching the kids, being pool cop, etc.

I will discuss other strategies and techniques that Dr. Pittman offers in her book in later posts. However, identifying your triggers is a great starting place to learn how to try to pluck the seeds of your anxiety before they have a chance to grow too long and entangled.

* Click here to subscribe to Beyond Blue and click here to follow Therese on Twitter and click here to join Group Beyond Blue, a depression support group. Now stop clicking.