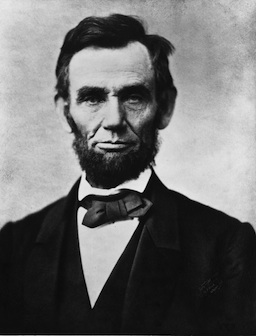

Abraham Lincoln is a powerful mental health hero for me. Whenever I doubt that I can do anything meaningful in this life with a defective brain (and entire nervous system, actually, as well as the hormonal one), I simply pull out Joshua Wolf Shenk’s classic, “Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness.” Or I read the CliffsNotes version: the poignant essay, “Lincoln’s Great Depression” that appeared in “The Atlantic” in October of 2005.

Abraham Lincoln is a powerful mental health hero for me. Whenever I doubt that I can do anything meaningful in this life with a defective brain (and entire nervous system, actually, as well as the hormonal one), I simply pull out Joshua Wolf Shenk’s classic, “Lincoln’s Melancholy: How Depression Challenged a President and Fueled His Greatness.” Or I read the CliffsNotes version: the poignant essay, “Lincoln’s Great Depression” that appeared in “The Atlantic” in October of 2005.

Every time I pick up pages from either the article or the book, I come away with new insights. This time I was intrigued by Lincoln’s faith–and how he read the Book of Job when he needed redirection.

Following I have excerpted the paragraphs from The Atlantic article on Lincoln’s faith, and how he used it to manage his melancholy:

Throughout his life Lincoln’s response to suffering–for all the success it brought him–led to greater suffering still. When as a young man he stepped back from the brink of suicide, deciding that he must live to do some meaningful work, this sense of purpose sustained him; but it also led him into a wilderness of doubt and dismay, as he asked, with vexation, what work he would do and how he would do it. This pattern was repeated in the 1850s, when his work against the extension of slavery gave him a sense of purpose but also fueled a nagging sense of failure. Then, finally, political success led him to the White House, where he was tested as few had been before.

Lincoln responded with both humility and determination. The humility came from a sense that whatever ship carried him on life’s rough waters, he was not the captain but merely a subject of the divine force–call it fate or God or the “Almighty Architect” of existence. The determination came from a sense that however humble his station, Lincoln was no idle passenger but a sailor on deck with a job to do. In his strange combination of profound deference to divine authority and a willful exercise of his own meager power, Lincoln achieved transcendent wisdom.

Elizabeth Keckley, Mary Lincoln’s dressmaker, once told of watching the president drag himself into the room where she was fitting the First Lady. “His step was slow and heavy, and his face sad,” Keckley recalled. “Like a tired child he threw himself upon a sofa, and shaded his eyes with his hands. He was a complete picture of dejection.” He had just returned from the War Department, he said, where the news was “dark, dark everywhere.” Lincoln then took a small Bible from a stand near the sofa and began to read. “A quarter of an hour passed,” Keckley remembered, “and on glancing at the sofa the face of the president seemed more cheerful. The dejected look was gone; in fact, the countenance was lighted up with new resolution and hope.” Wanting to see what he was reading, Keckley pretended she had dropped something and went behind where Lincoln was sitting so that she could look over his shoulder. It was the Book of Job.

Throughout history a glance to the divine has often been the first and last impulse of suffering people. “Man is born broken,” the playwright Eugene O’Neill wrote. “He lives by mending. The grace of God is glue!” Today the connection between spiritual and psychological well-being is often passed over by psychologists and psychiatrists, who consider their work a branch of secular medicine and science. But for most of Lincoln’s lifetime scientists assumed there was some relationship between mental and spiritual life.

In The Varieties of Religious Experience, William James writes of “sick souls” who turn from a sense of wrongness to a power greater than they. Lincoln showed the simple wisdom of this, as the burden of his work as president brought home a visceral and fundamental connection with something greater than he. He repeatedly called himself an “instrument” of a larger power–which he sometimes identified as the people of the United States, and other times as God–and said that he had been charged with “so vast, and so sacred a trust” that “he felt that he had no moral right to shrink; nor even to count the chances of his own life, in what might follow.” When friends said they feared his assassination, he said, “God’s will be done. I am in His hands.”

* Click here to subscribe to Beyond Blue and click here to follow Therese on Twitter and click here to join Group Beyond Blue, a depression support group. Now stop clicking.