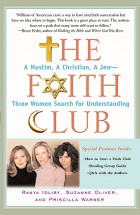

Following is one of my favorite excerpts from “The Faith Club”:

As I listened to Suzanne I felt that I was in the presence of someone with deep faith who had dealt with suffering and loss in a way that I couldn’t. I was a bit envious of Suzanne’s strong belief in God. I wished it would rub off on me. I wished I could believe that God would get me and my sister through the upcoming months that I knew would be so challenging.

When Ranya arrived, I filled her in on my sister’s condition [she was just diagnosed with breast cancer], and her eyes registered the concern and sympathy I needed. She asked about my sister’s treatment and encouraged me to take care of myself as I tended to her.

“I don’t know if I can handle this,” I confessed, getting teary again.

And then I decided to share with Ranya and Suzanne the source of my biggest doubts and fears.

“I’m not someone who handles stress very well,” I confessed. “I’m basically living in a state of low-grade panic. A state I’ve lived in all my life, essentially.”

I grew up in an unconventional household, I explained. My mother was an artist who held dream analysis workshops in our basement every week, shunning PTA meetings for gatherings of like-minded free spirits. In his forties, my father was diagnosed as a “mild” (in his words) manic-depressive. And, over the years, certain members of his extended family suffered “nervous breakdowns,” which were whispered about behind closed doors. They spent time in and out of mental institutions all their lives, and the constant awareness of this instilled in me a fear that I, too, would one day go crazy, suffer a “nervous breakdown,” disintegrate into madness.

This theory of mine was given validity by the one secret I had largely kept to myself: the terrible, debilitating panic attacks I’d suffered from the time I was fifteen years old. These attacks came out of the blue. They started as a rush of adrenaline, a jolt of electricity that caused my whole body to shake. My heart galloped; my lungs tightened up so badly that I felt like my chest was being crushed. My throat closed, and I couldn’t breathe. I gasped and gulped for air, like a fish on dry land. I thought I was dying. I felt nuts, sure that this had never happened to anyone else in their life, ever.

My first panic attack had taken place while I was working as a waitress at the Brown University Cafeteria in Providence. As I stood in my polyester uniform dishing out peas, surrounded by strangers and bathed in fluorescent lighting, I hyperventilated for the first time. I couldn’t breathe. I couldn’t work. I could barely stagger to the pay hone to call my parents and plead for a ride home. A doctor who made house calls examined me as I lay in my parents’ bed, terrified, and told me I was “just a little bit nervous.” He wrote out a prescription for Librium, a tranquilizer, and for the next thirty years I was left wondering what on earth was wrong with me.

I switched from Librium to Valium, but the panic attacks continued regardless of what I took, ate, thought, did, or felt. [I LOVE THAT SENTENCE!] I had no idea what caused them. Maybe I was mentally ill. Certainly things were out of control in my body and my mind. I suffered panic attacks at night, alone in my room, behind the cash register at my father’s supermarket, in restaurants, in college classes, at work in various ad agencies, in subways, buses and cars, even at the beach.

Despite my weak emotional constitution and looming panic attacks, I managed to build a good life for myself, with friends and boyfriends, academic and artistic successes. I met the love of my life and got married. I survived two pregnancies, despite several panic attacks, and gave birth to two wonderful, healthy sons. But I was a fraud. Nobody knew I was broken, that my body reared up and betrayed me on a regular basis.

“Maybe that’s why I have such a hard time declaring myself as a true believer in God,” I told Suzanne and Ranya. “My body has always felt out of control, which has made my whole life feel out of control. If your own body is in chaos, its’ hard to imagine a world of order, or a God who keeps things in order.”

Suzanne and Ranya didn’t look at God that way. They didn’t see God as keeping the world in order. “That’s because you’ve never felt the kind of frantic chaos within your own body that I’ve felt,” I told them. “You’ve never longed for that order.”

After reading a medical pamphlet a friend gave me, I linked my own panic disorder to the fact that I had a mitral valve prolapse, a common heart murmur. Sometimes a valve in my heart didn’t completely shut. And often my body reacted with a “fight-or-flight” response. I’d also traced my panic to a near-death experience when I was sixteen months old and hospitalized with a dangerously high fever, convulsions, and an acute infection. A doctor happened to find me in serious distress, alone in my bed and unable to breathe. He performed an emergency tracheotomy on me right then and there.

No wonder I worried about dying, I told Suzanne and Ranya. No wonder I worried now that I would not be a source of strength for my sister.

“I wish I believed in God,” I said out loud for the first time. Nobody in my family had ever talked about God. Not my father, my mother, my sister, or my brother. In twenty years of marriage, I’d had only one two-minute conversation with my husband about God.

Maybe, I realized as I spoke, all that was about to change. After the attacks of 9/11, I’d been afraid God didn’t exist. Now, with my sister sick, I wished with all my heart that I could believe in God. Maybe Suzanne and Ranya would show me how.