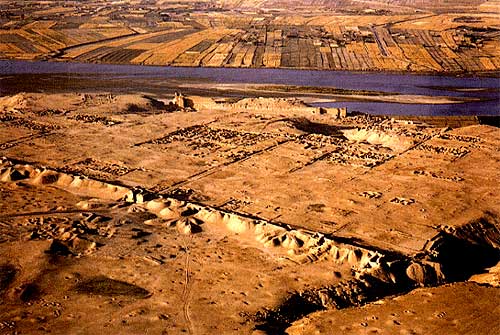

While we could focus on the general size and shape of this city and on its walls and citadels (see above), our interest must be more narrow in this post. In his recent important monograph Ramsay MacMullen analyzes in some depth early Christian church buildings and the early literary evidence about them as well (The Second Church. Popular Christianity A.D. 200-400, SBL 2009). We will be following his lead, and pursuing some of the important aspects of his study as it applies to the Dura Church.

That they built a purpose built structure in a home for baptism tells us a lot about the third century church, and perhaps the second century church as well, because the practice here comports with what we read in the Didache– a first or second century document which tells us about using running water and sprinkling or pouring water on the baptizands. Not for them the practice of John the Baptizer. Christian baptism seems to have distinguished itself from those practices depicted in the Gospels in various ways, not the least of which was the sacred name used in the act of baptism.

The second thing you notice at once from this picture above is of course the frescoes. We have murals of Adam and Eve, and also of Christ the Good Shepherd, a familiar image, and probably the very first painted image of Jesus in the history of Christian art. But this house is hardly just a place where baptisms were privately done.

What went on in these meetings? The archaelogical results indicate a space where perhaps 70 or so Christians could gather for worship or instruction at once. It is interesting that the baptistry is not part of the meeting hall itself. As MacMullen compares this structure to others like it from a slightly later period we can envision at the back of the meeting space a slightly raised area where the leaders of the worship would be seated facing people sitting on benches. The benches would be like those in the synagogue, with a central aisle and probably with the women sitting on one side and the men on the other. The catechumens in the later examples sat on benches up against the right and left walls of the nave. Clement of Alexandria takes us even further back, indicating there were

purpose built churches already by the end of the second century A.D.

What we notice as well from the close archaeological analysis of the space is that it was not a room for eating. That was done elsewhere in the house apparently, or possibly in the courtyard where the impluvium (rain catcher hole in the roof) would have been. MacMullen analyzes all the data closely and concludes the service would have been similar to those going on in the synagogue, it would have lasted about two hours, and it would have involved singing, prayers, Scripture reading, teaching, and preaching among other things. There would definitely have been leaders, and followers, and catechumens— three distinguishable groups. And as for the music itself, a priest from a church in Alexandria right at the turn of the 3rd century says this “if you want to sing and praise God to the music of the cithara or the lyre, no blame attaches to it” recalling the example of David (see MacMullen, p. 8). There was not requirement of pure acapella music.

What is interesting about the church in Dura is that clearly it had a sponsor who was wealthy, in a town of only 6-8,000 souls. Equally clearly the meeting involve more than just a handful of people. The space set aside could seat between 50-70 depending on the size of benches and amount of space allotted to each person. Had there been a grand departure from NT practice already in the pre-Constantinian era? Was there a big difference already in the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when it comes to worship and baptism and the like?

This is unlikely on several grounds. Firstly, Christianity was still an illicit religion when the church in Dura was built. This is why it is not a stand alone structure, but rather within a wealthy person’s house. Secondly, the obvious similarities in structure and murals and ablution pool in both the synagogue and the church here in Dura show that the church was still modeling itself to a significant degree on synagogue practice. It had elders or priests leading worship, just as in the synagogue. Indeed, there were bishops throughout this period supervising things, bishops who not merely could trace their links back to the turn of the first century figures like Ignatius, but to the leaders of earliest Christianity— the apostles and eyewitnesses, and prophets, and elders, and teachers of that period. Christianity had never known a period where its leadership structure was not hierarchial to some degree. The notion that it ever was is a modern myth perpetrated by low church Protestants fed up with badly run and clergy dominated hierarchial structures in our own day.

But there is more. The art in the murals and mosaics in Dura make clear that early Christians were not iconoclastic— they were not opposed to artistic representations of their God or their saints, or their Biblical heroes, or their martyrs. They believed art could be used in worship and honor God. We could have concluded the same from the many drawings in the catacomb churches in Rome as well.

I am fully in agreement with MacMullen when he stresses that the archaeological and inscriptional evidence is just as important as the literary evidence about early Christianity. As Jesus once said “the very stones cry out”, and in this case they cry out against incorrect interpretations about household meetings and house churches in the first century A.D. in Philippi or Corinth or elsewhere.

It can be no accident that Paul, approaching the end of his life, makes a point to address separately the leaders of the church in Philippi, calling them bishops or overseers and deacons, who can be distinguished from ‘God’s holy people in Christ at Philippi’ (Phil. 1.1). This is because there had always been and always would be such a distinction in the church of Christ. There were called and appointed leaders, and there were followers always. This of course did not mean that there was some rigid clergy/laity distinction. In one sense all were the laity, since it just means the people, and all were the clergy in the sense of the priesthood of all believers. This however in no way decided the more specific leadership structures of the early church– there were still leaders and followers, apostles and their co-workers. And there was still worship which bore some resemblance to synagogue worship with sermons, even though there was also the new element of the expression of Spiritual gifts.

Think on these things.