One of my best friends, A.J. Levine, a NT professor at Vanderbilt Divinity School was teaching at a penitentiary in the Nashville area named Riverbend. The subject on the occasion was the Lord’s Prayer. Bob Smetana in the Nashville newspaper reports what happened on that evening.

“Levine is also always learning from students, colleagues, and even

prisoners at Riverbend, where she has taught classes for years. There,

the inmates have become her students and friends. And sometimes, they

are her teachers.

She

says that Riverbend inmates, who she refers to as friends, often have

insights into the text that she never imagined. Take the Lord’s Prayer,

also known as the “Our Father,” where Jesus tells his followers to pray,

“forgive us our trespasses.”

Levine told her students that Jesus was originally

talking about economic deaths. And because sins are easier to forgive

than debts, the church interpreted that prayer to be about sin.

One disagreed, she

said.

He had been

through a program of restorative justice with the family members of the

people he killed. After a year of meetings, the family forgave him.

” ‘Lady,’ ” he said to

me, ‘that was worth more than any economic forgiving of debt could be,’

” she said. ” ‘Lady,’ he said, ‘Your problem is that you don’t

understand sin. And because you don’t understand sin, you don’t

understand forgiveness.’ And I thought, my God, he’s right.”

Sin, by whatever name you call it, is at the heart of the human dilemma. And now we have a recent celebrated treatment of the subject by Gary Anderson, professor of OT at Notre Dame. It has a catchy title—-SIN– a history. It has won the Christianity Today Biblical Studies book of the year award for this past year. With or without a title with pizazz, this is an important book for the current discussion of sin and in this post we will interact with this slender but powerful treatment of the subject.

Of course in our day and age sin has been trivialized, celebrated, redefined, berated, downsized, upscaled, and a few other modifications along the way. People don’t much like the term sin. They prefer terms or phrases like ‘mistake’ ‘error of judgment’, ‘unwise choice’, ‘immature conduct’. Why?

Because of course the term ‘sin’ implies something more than any of these euphemisms. For one thing, it implies a violation of an absolute standard set up by God Almighty. In short, the reason the term ‘sin’ gets under some skins, is because fallen person’s have an allergic reaction to the ‘eye in the sky’. They don’t want absolute ethical standards, and they sure don’t want absolute and final accountability with eternal consequences for our bad human behavior. It has been ever thus. So, what exactly does Gary Anderson contribute to this age old discussion?

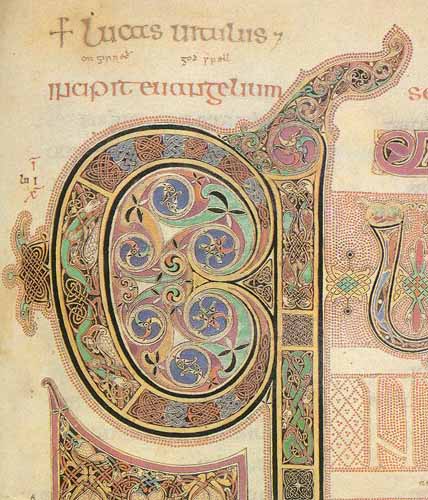

At the heart of Anderson’s argument is that while sin was, early on in the Biblical tradition, viewed as a weight or burden that someone must carry, or transfer (remember the scapegoat traditions), in time the dominant way of imaging things was in economic terms, namely sin was seen as a debt that someone had to pay for. Redemption in these terms meant a repayment of a debt, in order to be back in right standing with the Heavenly Banker. Anderson goes on to show, at some length, that this latter way of conceiving sin in economic terms affected the way NT writers conceived of the matter (see Luke’s ‘forgive us our debts’) and indeed the very way the death and resurrection of Christ was conceived, not a minor matter in NT theology.

What prompted Anderson’s odyssey through sin and its metaphors? He tells us in the Introduction that he was working through the Damascus Document (sometimes assumed to be a Qumran document, or coming from their library) and he noticed that it images sin not as a weight, but rather as a debt that had to be repaid or remitted (p. ix). Anderson goes on to say that the ‘original’ form of the petition in the Lord’s prayer was indeed ‘forgive us our debts’, and that this comports with what we find in later rabbinic literature where again sin is largely conceived of as a debt that must be repaid.

Before jumping on the Anderson band wagon at this juncture in terms of his analysis of the history of how we have conceived of sin, it’s time for me to raise my hand and say, honestly I do not think that the ‘debt’ reading provides us with the earliest or most accurate reading of that petition in the Lord’s prayer. In the first place, Luke clearly enough has the word hamartia which is properly translated ‘sin’. It is the more generic word for sin, and certainly is not a technical term for debt. What about Matthew? Well Matthew has the word opheilema which while it can mean ‘debt’ in economic contexts, also certainly can mean wrong, sin, or guilt in other contexts. My preference for some such translation as ‘sin’ rather than ‘debt’ is not because I am a Methodist (who pray forgive us our trespasses) rather than a Presbyterian (who pray forgive us our debts), but because while Jesus was very concerned about poverty and its root causes (see my recent book Jesus and Money), he knew very well that ultimately; sin is the root cause of all sorts of evil, including poverty. Jesus did not come to ransom us from our debts, he came to give his life as a ransom for sin (Mk. 10.45). It follows from this that since the Lord’s Prayer is dealing with primary and primal matters, it is far more likely that Jesus would talk about forgiveness of sins (one form of which can be debts) than forgiveness of debts in the purely economic sense of things.

In other words, I think that before we canonize the sin analysis of Anderson and proclaim it definitive, there are some serious questions to ask about that analysis. And it would be a sin not to probe the matter deeply 🙂 So here is the overture to such probing. In my next post we will consider the early part of Anderson’s fine and very readable study.