The Carlos Museum at Emory has a nice small collection of Greco-Roman remains, particularly busts which I thought I would share with you. The above bust should be familiar— it is Julius Caesar himself.

As you can see from this bust of a domina, a patrician ‘ruler of the house’, the Romans preferred realism to idealism in portraiture, unlike earlier periods of Greek statuary. I don’t know about you, but I would rather not have had to confront this mean looking granny on any issue. Notice the interesting head-covering, worn by someone who was long since married.

Besides giving a sense of a young woman’s hairdo in that period, it is hard to see, but this priestess also has a headcovering. In general, both Roman men and women wore headcoverings at the juncture when they were making some offering to a god. This is even true of the emperor, and even after the rise of the Emperor cult.

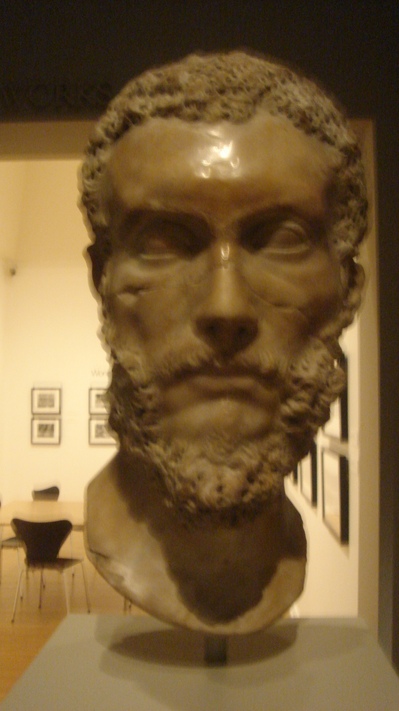

Here we have a philosopher or rhetorician, and probably Greek, as Greeks rather than Romans tended to favor beards.

Here we have a properly togaed patrician woman, giving you a sense of the voluminous clothing women wore. Modesty was what was expected of women in their dress, especially when they went out in public. Greco-Roman culture was a honor-shame culture with men expected to uphold the public honor of the family, and women protecting the inner life of the family from shame (chiefly by avoiding sexual infidelity).

The use of marble in flooring, often in intricate patterns was of course a sign of wealth. This little piece of floor shows you some of the artisanship of the age, much of which skill, we have lost.

This may appear to be the ancient equivalent of a bird bath, but in fact, it has a picture of a sacrificial altar with a bird on it. In Greco-Roman religion, there was strangling of birds, sometimes even up next to a statue of a god. Why? In order for the life breath in the animal to give further life to the deity. The reference to ‘things strangled’ in the Acts 15 decree is probably a reference to this practice.

Grace art and grave steles are important as they reveal a good deal about Greco-Roman beliefs about the afterlife and the underworld. Here we probably see a husband and wife communing with one another. The fact that the husband is reclining but the wife is not, may suggest he has died. Part of the rituals of mourning were holding a birthday or death day party on the tombstone in years following the death of the beloved. There were even pouring tubes into the sarcophagus so the deceased’s spirit could join the party. Greco-Roman people believed the spirits of the dead lived on. Most went to Hades, but the exceptionally virtuous went to the Elysian Fields.

This little podium or stand shows winged horses. Part of Greek and Roman mythology. According to one tradition, Helios, the sun god road a chariot across the sky with winged horses.

Oops. If you will turn your head side ways, you will see a beautiful bit of grave art. Which looks as follows right side up!

Here we have a very beautiful traditional motif, the husband and wife together, in death, as in life. In this case the shrouded wife is probably the deceased, which the husband is holding on to for dear life. Notice the fiscus in his hand as well which suggests he was a senator or some legal or political figure, and certainly a patrician and literate. All of this sort of ancient art helps us get a better sense of the culture of the NT era, for ‘the past is like a foreign country, they do things differently there.’