What is it like for a high school student in the 1970’s to discover she is pregnant as a result of unprotected sex with her sweetheart who then hides the truth from her family and friends until it is too late to deny it? Compound that reality with a series of untruths in an effort to quell shame and protect others, including the father, until many years later? Add to it, her success in reconnecting 18 years later, with the daughter she gave up for adoption, only to discover that there isn’t always a nice, neat, fairy tale flower petal strewn path to reunion. Smythe opens the door to her heart and allows the reader to peek inside.

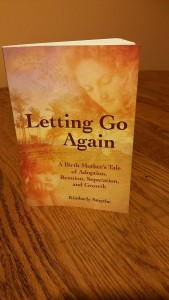

That is the storyline encapsulated in Kimberly Smythe’s fledgling book entitled: Letting Go Again- A Birth Mother’s Tale of Adoption, Reunion, Separation and Growth. Smythe introduces herself to the reader as the natural mother of a baby girl she refers to as ‘Kelcey’. She then shares that the more current PC title of ‘birth mother,’ by which she was later referred, felt like a demotion of sorts and way of distancing her from the intimacy of having carried this child for nine months, only to lose her while in a home for unwed mothers. As an adoptive mother and former foster parent, I appreciated hearing the perspective of a natural mother.

As a result of having been raised as an ‘army brat,’ Smythe was accustomed to moving often and never quite felt like she fit in, which is common among ‘third culture kids’. Throughout the book, she is honest about the deep desire to feel loved and accepted, which led to decisions that brought with them, pain and challenge, as well as overcoming resistance and finally revelation and reconciliation with her own lonely inner child.

One thing that became abundantly clear throughout the pages is that had Smythe felt more comfortable with speaking her truth, before Kelcey’s birth, after the adoption and following their meeting and on again-off again relationship, rather than tiptoeing around it and making assumptions about others’ feelings and perceptions, much of the pain she experienced might have been avoided. Hers was not an unusual journey for its time, nor were her behaviors unexpected given her mindset. She seems to have felt that not only were her actions shameful, but indeed, she, herself was as well.

Smythe spends much of her time with Kelcey as an adult, attempting to overcompensate for that belief. Blessedly, she seeks and finds supports, sets appropriate boundaries, and with great courage, steps away from the destructive patterns that threatened to pull her under.

Having spent much of her life in Hawaii, Smythe speaks with reverence about the Hawaiian concept of Hanai which refers to the idea that it is a privilege to take the child of another into one’s home and heart. She views the adoption of Kelcey by her new parents to be such an opportunity and as such, offers proceeds from the book to the Hanai Foundation 501c3 non-profit organization.

The Hanai Foundation’s Mission statement is:

“To honor nurturers and their families by supporting people and organizations that focus on individual wellbeing.”

Smythe honors her relationships with her first child, the three who follow, her husband, siblings and parents, as well as all of the women who give birth and those who adopt these children, since they are all companions on her journey of love and loss.