What would it be like to feel like an outsider in the midst of a crowd; an ‘other’ while surrounded by those whose appearance differs from your own?

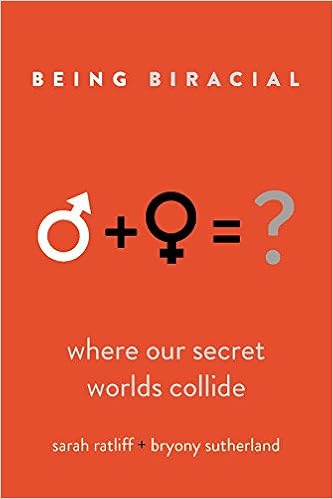

Being Biracial: Where Our Secret Worlds Collide was penned by Sarah Ratliff and Bryony Sutherland as a means of sharing their stories and those of several others. A heart and soul baring endeavor; each woman approaches the topic from their unique perspective. Bryony is a White woman, married to a Black man and their children are mixed. Her social circles contain people of various origins. Sarah is self described as, “Caucasian, AfricanAmerican and Japanese. My father’s father was born and raised in Germany. My paternal grandmother was Dutch and Irish. My maternal grandmother was Black and she—like most African-Americans—was a descendent of slaves from West Africa.”

Sarah’s family history is gut wrenching. Her paternal grandfather was a racist, sexist and homophobic man who made her father watch a young AfricanAmerican child drown when he could have been saved. When he chose love over hatred, Sarah’s father walked out of her grandfather’s life. Years later, after Sarah and her two brothers were born, his father re-entered, referring to his grandchildren as “criminal mistakes”. The door closed again.

Fast forward and Sarah marries her husband Paul who is AfricanAmerican and they move to an organic farm in Puerto Rico where they raise goats and bamboo and Sarah who is a prolific writer, founded her own content marketing company. There they feel culturally enriched and are rarely looked at as being the odd man or woman out, since their neighbor’s complexions and origins are varied.

How to manage self acceptance in a world that sets standards for ‘appropriate’ appearance and means of relating is one of the strong suits of this book. Some were considered not Black enough or White enough to be embraced by either group. Even in the Black communities in which some of the writers live, there are gradations of privilege based on hue and tone of skin.

It outlines the struggles the writers have had just to maintain a sense of dignity in the face of rude stares and vilifying comments. Even the comment the “Irish, Italian and Scottish; Mother of Irish, Italian, Scottish and Puerto Rican” daughter received, “She’s so beautiful. Is she adopted?” Could they not have left it at the initial compliment?

One of the authors, a half Asian, half Scandinavian man, posits,”That sense of displacement you have, because you’re from two different worlds? Don’t curse it. It’s not that you don’t belong. You’ve been given something else instead. You’ve been granted the freedom to choose who you want to be. No—this freedom has been foisted upon you. You cannot choose either side because you are not merely one of your two halves—you are both, and you are neither. You are the choices you have made, and nothing else.”

Another has a more raw and gritty way of describing herself, “Well, I am White. And Black. And who knows what else; the family stories are many and varied. I am a mongrel, a mutt, a half-breed, a Heinz 57. I’m mulatto, Biracial, mixed. I am all of these things and none of these things.”

A Vietnamese American fields these all too common questions, “What are you, anyway?” (Or various forms thereof, such as “What’s your background?”, “What ethnic mix are you?” or, from the confident ones, “Are you [insert assumed ethnicity here]? You look like you’re [insert assumed ethnicity here].”

Russian Jewish Jeremy refers to himself as a chameleon who is able to adapt to the environment in which he finds himself, with friends of various ethnic backgrounds.

The mother of two mixed race children encountered vitriol from the mother of a White child when she corrected the boy for telling her son that he couldn’t use the sliding board at a McDonalds’s playground because of his skin color.

Closing out the book, co-author, Bryony who is White and the mother of three Caribbean Black and White children shares her experiences. She had asked her husband who is Black if he had experienced racism. Blessedly rareloy, he told her, that some in his life asked him “what was wrong with mixing with his own kind. Once. And in the research for this essay, I also discovered his estranged father’s reaction to the first time he brought me home was to ask why he was wasting his time on a White girl.” When she asked her oldest son how he self identified, he told her that to choose only one side of the family was to discount the other and he wasn’t willing to do that. Clearly, they taught him well.

Being Biracial reminds us that beneath the sheath that cover our skin and bones, beat hearts that long for love and acceptance.