By Orson Scott Card

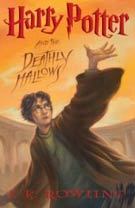

A few days from now, J.K. Rowling will bring the Harry Potter series to an end.

Well, actually, she brought it to an end months ago. But by the end of this week, we will finally find out what end she decided on.

I hear all kinds of speculation. Some examples:

1. Because Harry Potter is a Christ Figure, he has to die.

I think this is just silly. First, Harry Potter is not a Christ-figure in the allegorical sense — Rowling has not been making his life parallel the life of Jesus in any significant way. Indeed, if there’s any Christ-figure in the books, it’s Harry’s mum. She’s the one who gave her life to save him.

And when it comes to resurrection, Voldemort is the main resurrectee in this series — please don’t tell me anyone thinks he represents Jesus of Nazareth. I think he bears more resemblance to Hitler of Austria or Stalin of Georgia or Pol Pot of Khmer.

Come to think of it, even those evil souls at least claimed to be doing their deeds to serve a noble cause. Voldemort is more like a really greedy CEO of a corporation, who steals ideas from everybody else, never creates anything of his own, but makes sure that other people’s creativity makes him as much money as there is to be made. You know, the Microsoft of the Wizarding world.

Speaking in literary terms, if Rowling really does kill off Harry — perhaps with the same silly idea that Arthur Conan Doyle had when he killed of Sherlock Holmes so he didn’t have to write about him anymore — then it would be hard to imagine a worse mistake by any author, ever.

Why? Well, in commercial terms, it would be insane. She thinks she’s done with Harry, but ten or twenty years from now, even though she’ll still be fantastically wealthy, she will be a much better, more mature writer — and a much wiser, more knowledgeable human being. (Or at least one hopes so; not all writers grow up, but most do.) She will want to return to the wizarding world she created in her youth as a writer and tell more stories in that setting. She also won’t mind the ten million dollars that she will be offered by publishers (if she does it soon enough).

But leave aside commercial considerations. There is a compelling artistic and moral reason why the death of Harry Potter would be a ridiculous mistake.

It’s this simple: What did Harry’s parents die for? It wasn’t to stop Voldemort’s career — they were in hiding from him, and had not chosen themselves to bravely face him and destroy him. Their sole purpose was to protect their son; it was merely a happy accident that in the midst of the tragedy of their deaths, their love for Harry ended up all but killing Voldemort himself, leaving Harry mostly unscathed.

Everything in the Harry Potter series points to Harry confronting Voldemort and winning. Now, there’s a long tradition of the hero sacrificing his life to save others. There’s also a long tradition of the Twilight of the Hero: Beowulf being brought down by the dragon as he saves his people; Arthur’s body being carried off to Avalon while Britain succumbs to the invaders.

So Rowling might have visions of creating a tragic epic.

If so, it’s a cruel trick to play in a book for children.

Children have an enormous capacity for tragedy — contrary to what many adults think, they can deal with death in fiction quite readily, mostly because they rarely understand fully what it means. They just know it’s very, very important, and much to be avoided if possible.

What children have no tolerance for is cheating. Not playing by the rules. And there is nothing in the Harry Potter series that requires that someone die in order to overcome evil. If for six books we had been told that the only way to permanently kill someone like Voldemort is for the killer to be willing to die himself in the process, then great, we’d be prepared for it, and Harry would enter into the combat knowing his demise is sure. We might hope that there’ll be a last-minute “out” from the law, but we would be prepared.

More to the point, children would be prepared.

But there is no such rule, unless she tries to pop it up at the last minute (and no matter how long the book is, anywhere in “Deathly Hallows” would be “the last minute” when the series is seven books long). So if Harry is killed, every reader — including the most naive child — will know that Rowling chose to do it when she didn’t have to. We will feel — correctly — that we have been jerked around by an author who does not care how much love we have invested in the character she created at such length.

We will feel, in short, cheated. And we will be right.

She will have broken the compact between writer and reader. Here’s how the compact works, though it is almost never said in words:

The Storyteller’s Compact

I, the author, will bring you into a world which I made up, so that everything that happens is not true. You will pour your emotions into the characters and situations that I create, and spend hours and hours reading it.

In return, I promise that even though nothing is true, everything will feel truthful — events will make a kind of moral and logical sense in a way that the real world rarely does. Characters’ decisions will feel truthful given what I have told you about them. I will follow the rules I set up in the story.

By the end, the memories that you, the reader, have allowed me to insert into your mind will feel good to you. Not necessarily happy or pleasant, but Good. As the godlike creator of a fictional world, I will prove myself to be a god who loves Good and ennobles it in my fiction.

(Please keep in mind that I called this “The Storyteller’s Compact.” There is another one, called “The Literary Compact,” and it goes like this:

(I, the author, will provide you with words. The way the words are arranged will impress you no end with my skill at word-arranging. I will give you many opportunities to feel very smart about how you catch all the references I have made to other literature, and how you decode all the symbols and solve all the puzzles I have created for you. At the end of the words, you will be almost as impressed with yourself for having read them as you are impressed with me for having arranged them so artfully, and in return you will honor me with prizes and grants and tenured positions.)

2. Hagrid’s gonna die.

This is an even dumber choice than Harry dying. In fact, it is clear in the last two books that Rowling has lost interest in Hagrid. Nothing he does matters much to the outcome; his contribution consists of trivialities like overhearing something and mangling the message in the retelling. He is only brought back because audiences have affection for him. He is there for comic relief, and Rowling surely feels the irrelevancy of his character to the very serious conflict that is coming up.

Not that Hagrid won’t play an important role. She will bring back everybody who ever mattered — that’s what you do in an ending. I wouldn’t be surprised if Cedric Diggory pops up again in some way. Or Tom Riddle’s relatives. But Hagrid’s death will not feel Important the way that deaths need to feel Important in this final novel. He has been used too comically for too long to be a figure of tragedy.

Compare him to Falstaff, if you will. Not the same character at all, but used in much the same way — as a figure of outrageous fun for a time, until he is no longer funny. Hagrid has reached that point. Just as the business with Hermione trying to liberate the house elves became cloying and Rowling finally stopped wasting our time with it, she has stopped wasting our time with trying to maintain Hagrid as a major character. He is only good for cameos now. His time at center stage is done.

3. Dumbledore is coming back.

It certainly looks to me as if Rowling has set him up to come back — a man who is tied to a phoenix, whose “burial” is a magical event, and whose death was carefully orchestrated by himself certainly could come back.

But I think Rowling also understands that as long as Dumbledore is alive, any victory will be his, not Harry’s.

Now, we can look at “Lord of the Rings” and see that Tolkien made the choice to bring Dumbledore — er, I mean Gandalf — back from the dead.

But I personally believe that was something of a mistake. I didn’t mind that he did it; or at least not much. But the first time I read “The Two Towers” and Gandalf pops up alive after all, I felt cheated because the characters and I had spent so much grief on him.

And through the rest of the story, Gandalf doesn’t actually do much.

OK, I know, he’s running around all over the place, liberating Theoden from Saruman and Wormtongue, snatching Faramir’s body from the flames, and so on. But in fact, he was not needed in a storytelling sense. Tolkien could easily have found other mechanisms to accomplish all that Gandalf did.

In fact, we like best the things that non-Gandalf characters accomplish: Faramir’s refusal to seize the ring; Eowyn’s and Merry’s stabbing and slaying of the leader of the Nazgul; and, above all, everything Frodo and Sam and Gollum do on the road to the Orodruin.

Gandalf, like Dumbledore, had already set a plan in motion. It would actually have been more fulfilling for Gandalf to remain dead and then watch his plans unfold. But we would see that the plan could only go so far, and then the choices and courage and doggedness and loyalty and creativity of other characters would be required to bring about the goals that he had laid out.

And despite Tolkien’s efforts to keep Gandalf as busy as possible, he makes sure that Gandalf does not stop by and check in on Frodo and Sam — he keeps Gandalf effectively dead as far as they are concerned. Why? Because Tolkien knew, as Rowling does, that the hero is not a hero if the god-figure does all the work for him.

For that is what Gandalf and Dumbledore both are: The paternal god-figure, bestowing revelations and making plans without informing anybody of all that they’re doing. Each person gets a piece of the puzzle; each person gets a task to fulfill, without necessarily being informed of anything more than they need to know in order to play the parts the god-figure designed for them.

The result of leaving Gandalf alive in Lord of the Rings is that he is diminished. It would have been a stronger story if he had stayed dead.

I say this knowing that I’m speaking of the greatest work of literature in the twentieth century. (Ulysses schmoolissies.) But greatness does not imply, any more than it is implied by, the absence of mistakes.

And that means, of course, that the Harry Potter series might have — indeed, does have — its share of mistakes as well. Greatness comes from having a story so strong that all mistakes are forgiven.

I am betting that Rowling’s instinct was closer to the correct decision made by Isaac Asimov in the Foundation series — the decision that the original god-figure, Hari Selden, should be dead and stay dead, and that his fatelike plan should even be subverted by a force he could not have planned on, forcing the characters to improvise.

So I believe that Dumbledore, cute and beloved as he is, will stay dead because if he remained alive, the final victory would be his; while if he is dead, the final victory will be Harry’s — along with whoever else helps and supports him in the end.

4. Snape will…do something really important. And he’ll die. Or not.

Here’s the great strength — and potentially the greatest weakness — of this series. Snape, who at first was merely a red-herring character, designed to make us think in book one that he was the villain when someone else really was, has emerged in the last few books as the single most fascinating character, the one whose choices are most in doubt.

In a way, Harry Potter himself has become as fictionally uninteresting as, say, Frodo — we want him to prevail, we know that only he contains the power to destroy Voldemort (because they are so closely linked). Of course we care about him, but he has lost the capacity to surprise us. Or rather, if Rowling has him do something that surprises us, we are very likely to respond angrily, feeling that she has cheated — that she has made him act out of character.

But Snape has been set up as a great mystery: Is he bad or good? As he speaks to Harry during their minibattle after the death of Voldemort, is he taunting Harry or trying to teach him? Was Dumbledore right to trust him?

Of course, I have my own answer to that and have written at great length about it in an essay that was published in a Borders-only book called “The Great Snape Debate”— which I, utterly without bias, believe you should have read already if you’re serious about these matters.

(For a taste of what the book contains, feel free to read my whole essay, reprinted [with the publishers’ permission] in issue 5 my own fiction magazine, Orson Scott Card’s InterGalactic Medicine Show. You can read the whole essay without signing up for the magazine; just click on it from the table of contents.

(And if you think anything I say is really “utterly without bias,” I’m assuming you also believe in Sasquatch and that Jim Cameron really found the body of Jesus.)

5. This last book will end the story of Harry Potter in such a way that the whole series will continue to matter as literature for centuries to come.

Only a handful of books — even books that were once wildly successful — remain Important for generations.

This does not mean that the other books “failed” somehow. Just because very few people read “The Robe” or anything else by Lloyd Douglas does not change the fact the for a time — the 1940s and 1950s — he was as important and widely read in America, at least, as Stephen King.

If a writer is important to the audience that he writes to, then even when he is no longer read, the ramifications of his literary achievements are still felt. We still live in a world partly created — and much improved — by Harriet Beecher Stowe’s “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” The book is unreadable now, except by graduate students, who generally must mainline No-Doz to get through it. It is partly because of Stowe’s success — slavery is no longer considered normal and acceptable — that reading her book is no longer fueled by a sense of discovery and outrage; and without that to provide urgency, the flaws of her writing take over.

Even stories that have become icons can become unreadable in the original. Everyone knows the story of “Tarzan,” but the original novel is so floridly overwritten that only children have the patience and naivete not to skim or skip the endless dull parts.

But there are stories that, as written, remain compelling through the ages, at least to enough people — and enough writers — that the story and the manner of its writing continue to be part of the internal biography of a civilization or civilizations.

Shakespeare was such a writer, though not with every play. Tolkien was such a writer. Jane Austen, Emily Bronte, Chaucer, Goethe, Homer.

Most literary giants are between those two extremes: Heroes, not gods. They are not fully immortal, yet their achievements are far greater than mere mortals. They prevail for a time — sometimes a long time — but eventually fade, to dwell at last in the province of scholars rather than the general public.

So the question is: Will Rowling end the Harry Potter series in such a way that her books will become a historical curiosity? “Do you remember when Harry Potter was such a phenomenon that everybody was reading the books, even adults all by themselves in airports?” “Harry who?”

Or will Rowling end the series so compellingly that a hundred years from now, people need only say “Harry Potter” or “Snape” or “Voldemort” and every moderately educated person will know exactly what those words are supposed to mean?

The way I can say “Trojan horse” or “King Lear’s daughters” or “Heathcliff” (needing to say “not the cat” is merely a temporary aberration) or “Darcy” or “Remember: Frodo gave his finger for you” and expect that everyone will know what I’m referring to.

She could go either way.

There was a time when every educated American had read Lew Wallace’s “Ben-Hur” or had seen a stage production of it. It was the most important, widely-read American novel of the second half of the 19th century. It was a sprawling epic; it touched on almost every aspect of the single most important root of American culture: the Christ story.

The book — and the performances of it, though movies rather than plays after a while — continued until the great God-is-dead revolution of the late 1960s. That was a long life for a book. It was still read by volunteers right up to that time — as far as I’ve heard, no one ever required that students read it or put it on a list of the “best American literature ever.” It has been kept alive by the devotion of its audience. America had to reject Christianity as part of its public life before “Ben-Hur” finally receded — perhaps temporarily — into oblivion.

So it may happen that some great cultural change will eventually kill the importance of the Harry Potter series to the western world.

But for right now, we seize upon Harry Potter and hold him as an important icon. He has made readers out of children who hated everything they were forced to read at school; people who could hardly bear to read a whole magazine will plow through hundreds of imperfect pages because they are so passionately interested in knowing how the story comes out.

In a faithless age, an age that denies transcendence and tries to reduce human life to the equations of chemical reactions within and between neural cells, the Harry Potter story tells us that obstinate courage, the willingness to fling aside rules in order to confront and thwart evil, is so important that it’s worth dying for.

These books have told us that sometimes the world needs saving, yet those who would reach out to save it are despised, treated with public scorn.

I do not assert that Rowling herself would apply these meanings to, say, Tony Blair or George W. Bush or Al Gore — part of her greatness is that, except for a brief dollop of puerility when she had a new Muggle PM get briefed about a crisis in the wizarding world, she has stayed away from contemporary politics, even allegorically.

But I do say that whatever our politics might be, almost every ideological camp can feel that Harry Potter somehow speaks for them, for what they must accomplish.

In a way, it’s a futile hope: Can we really expect any one person to have the kind of magical power that Harry has?

In another way, though, Harry offers that hope precisely because he isn’t actually the best at anything except Quidditch, and even then he can be beaten by cheaters. Hermione is smarter and better at magic — so is Snape. And to say that Harry’s great virtue is courage is misleading — his enemies are not all cowards, and he is not without brave allies.

Harry has advantages because of his understanding of Voldemort, his links to him. Harry’s father was a taunting bully for a time — but, like Harry, he became something noble and fine precisely because at the moment of crisis, he did what was right on a sudden impulse. The personal consequences might be dreadful, as when he got in serious trouble for magically thwarting dementors in the Muggle world. But he will do it, almost without thought, almost by reflex.

And that is something that we — we Americans, we Anglophones, we Westerners, however you want to define the group that constitutes the Harry Potter community — are hungry to believe about ourselves and about our heroes and leaders in the real world, whoever they might be.

That is why so much is riding on how Rowling has chosen to end the Harry Potter story. She is telling us the story that we need to believe in, because we hope that, in the crisis, we will always have Harry Potter to lead us.

Indeed, if there is any real-world figure that Harry Potter resembles, in a wonderfully absurd way it is Winston Churchill. No, Harry Potter does not lie in bed half the morning or wander naked around the house, and he does not move through the world with a solid jolt of alcohol in his veins.

But he has the magic when the magic is needed, however much the world might despise and even persecute him in between. He emerges to do the job, and does it, sometimes despite his own mistakes, because of his dogged courage and loyalty, because he will never, never, never, never surrender.