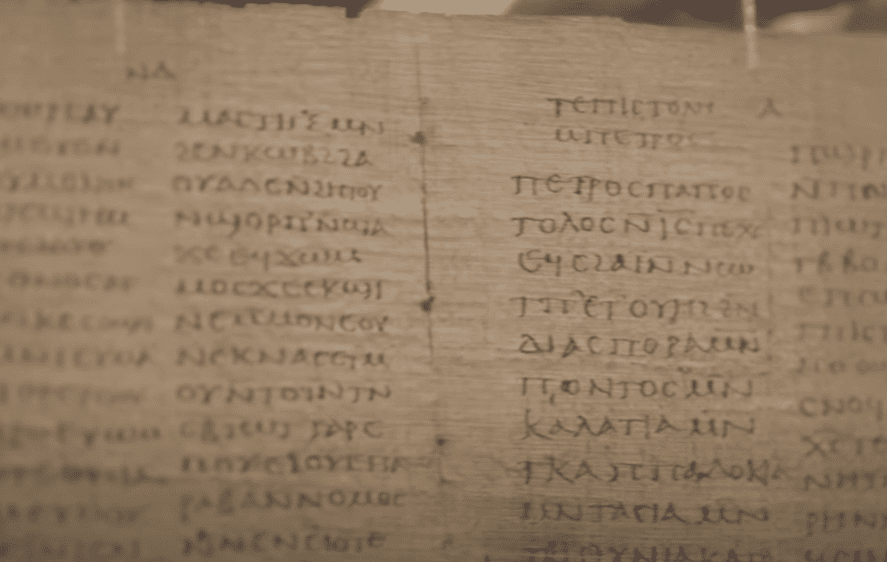

An archaic manuscript with the oldest complete versions of two significant biblical texts, the book of Jonah and 1 Peter is being auctioned at Christie’s in London with an expected price of up to $3.8 million. Known as the Crosby-Schøyen Codex, this rare artifact dates back to the third and fourth centuries and originates from Egypt, according to Christie’s. It’s part of a larger auction by Christie’s that features a variety of important manuscripts spanning 1,300 years of cultural history.

Among the other notable items are the Codex Sinaiticus Rescriptus and the Geraardsbergen Bible, which together trace significant periods of religious and cultural transformation. Eugenio Donadoni, a senior specialist in books and manuscripts at Christie’s, described the Crosby-Schøyen Codex as a cornerstone of early Christian faith, emphasizing its value in understanding the spread of Christianity around the Mediterranean. Donadoni noted, “This codex is a self-consciously assembled compilation of texts, particularly significant for celebrating one of the earliest Easters and for its connection to monastic communities in Upper Egypt,” The Telegraph quoted Donadoni as saying.

The manuscript was written by a single scribe over 40 years and was initially in the possession of the University of Mississippi after being discovered undisturbed for about 1,500 years. Dr. Martin Schøyen, a Norwegian manuscript collector, later acquired it in 1988, and it has since been recognized as the oldest book in private hands, according to The Times. Experts have placed the creation of the Crosby-Schøyen Codex at a time when Christians were still defining their identity, heavily influenced by Jewish traditions. This period marks a significant chapter in religious history, occurring before the official recognition of Christianity within the Roman Empire by Emperor Constantine in 312 AD.

Donadoni was quoted as saying, “It’s one of the three major finds of the 20th century that revolutionized the study of Christianity. We’re talking about early Christians finding their feet as Christians, still steeped in Jewish traditions.” Donadoni explained that the codex was likely produced as a liturgical book intended for religious celebrations such as Easter, making it an invaluable resource for understanding early Christian rituals and beliefs.

“In that time and place, the monk and the manuscript were both new categories in the world,” says Christie’s. “The innovative thing about his planned anthology was its physical form. This was not a scroll — which for centuries had been the standard medium for writing in the Graeco-Roman world. It was a codex. It consisted of rectangles of papyrus stitched together to make a kind of pamphlet, 136 pages long. This was, in other words, an early exemplar of the book as we now know it.”

It adds that the monk likely belonged to the initial cohort of individuals who embraced the monastic life, committing to austerity and devout worship. This movement had just started to evolve, inspired by Pachomius, commonly regarded as the pioneer of Christian monasticism. It is possible that the scribe was one of Pachomius’ followers.

The preservation of the Crosby-Schøyen Codex is attributed to Egypt’s dry climate, which has played a crucial role in the survival of many ancient manuscripts.