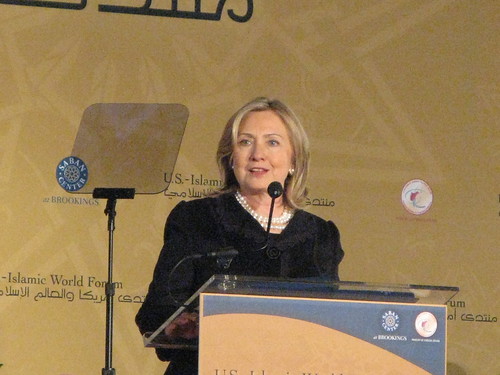

I was incredibly honored to meet Madame Clinton last night, introduce myself, shake her hand, and I think even give her the correct URL to the blog, though that last bit is a bit sketchy. I was frankly overawed by her. An incredible woman and powerful intellect.

Here are her remarks from last night. I have pictures and even some video I will post later.

Thank you, Strobe. It is a pleasure to join this first U.S.-Islamic World Forum held in America. His Highness the Amir and the people of Qatar have generously hosted the Forum for years. I was honored to be a guest in Doha last year. And now I am delighted to welcome you to Washington. I want to thank Martin Indyk, Ken Pollack and the Saban Center at the Brookings Institution for keeping this event going and growing. And I want to acknowledge all my colleagues in the diplomatic corps here tonight, including the Foreign Ministers of Qatar and Jordan and the Secretary General of the Organization of the Islamic Conference.

Over the years, the U.S.-Islamic World Forum has offered a chance to celebrate the diverse achievements of Muslims around the world. From Qatar — which is pioneering innovative energy solutions and preparing to host the World Cup — to countries as varied as Turkey, Senegal, Indonesia and Malaysia, each offering its own model for prosperity and progress.

This Forum also offers a chance to discuss the equally diverse set of challenges we face together around the world – the need to confront violent extremism, the urgency of achieving a two-state solution between Israel and the Palestinians, the importance of embracing tolerance and universal human rights in all our communities.

I am proud that this year we are recognizing the contributions of the millions of American Muslims who do so much to make this country strong. As President Obama said in Cairo, “Islam has always been a part of America’s story,” and every day Americans Muslims are helping write our story.

We are meeting at a historic time for one region in particular: the Middle East and North Africa. Today, the long Arab winter has begun to thaw. For the first time in decades, there is a real opportunity for change. A real opportunity for people to have their voices heard and their priorities addressed.

This raises significant questions for us all: Will the people and leaders of the Middle East and North Africa pursue a new, more inclusive approach to solving the region’s persistent political, economic and social challenges? Will they consolidate the progress of recent weeks and address long-denied aspirations for dignity and opportunity? Or, when we meet at this Forum in five years, will we have seen the prospects for reform fade and remember this moment as just a mirage in the desert?

These questions can only be answered by the people and leaders of the Middle East and North Africa themselves. The United States certainly does not have all the answers. In fact, here in Washington we’re struggling to thrash out answers to our own difficult political and economic questions. But America is committed to working as partners to help unlock the region’s potential and realize its hopes for change.

Much has been accomplished already. Uprisings across the region have exposed myths that for too long were used to justify a stagnant status quo: That governments can hold on to power without responding to their people’s aspirations or respecting their rights. That the only way to produce change in the region is through violence and conflict. And, most pernicious of all, that Arabs do not share universal human aspirations for freedom, dignity and opportunity.

Today’s new generation of young people rejects these false narratives. They will not accept the status quo. Despite the best efforts of the censors, they are connecting to the wider world in ways their parents and grandparents could never imagine. They see alternatives. On satellite news, on Twitter and Facebook, and now in places like Cairo and Tunis. They know a better life is within reach – and they are willing to reach for it.

But these young people have inherited a region that in many ways is unprepared to meet their growing expectations. Its challenges have been well documented in a series of landmark Arab Human Development Reports. Independently authored and published by the United Nations Development Program, they represent the cumulative knowledge of leading Arab scholars and intellectuals. Answering these challenges will help determine if this historic moment lives up to its promise. That is why this January in Doha, just weeks after a desperate Tunisian street vendor set fire to himself in public protest, I talked with the leaders of the region about the need to move faster to meet their people’s needs and aspirations.

In the 21st century, the material conditions of people’s lives have greater impact on national stability and security than ever before. The balance of power is no longer measured by counting tanks and missiles alone. Now strategists must factor in the growing influence of citizens themselves — connected, organized and frustrated.

There was a time when those of us who championed civil society, worked with marginalized minorities and women, and focused on young people and technology, were told our concerns were noble but not urgent. That is another false narrative that has been washed away. These issues – among others – are also at the heart of smart power – and they must be at the center of any discussion attempting to answer the region’s most pressing questions.

First, can the leaders and citizens of the region reform economies that are overly dependent on oil exports and stunted by corruption? Overall, Arab countries were less industrialized in 2007 than in 1970. Unemployment often runs more than double the world-wide average, and even worse for women and young people. While a growing number of Arabs live in poverty, crowded into slums without sanitation, safe water, or reliable electricity, a small elite has increasingly concentrated control of the region’s land and wealth. The 2009 Arab Development Report found that these trends – and I quote — “result in the ominous dynamics of marginalization.”

Reversing this dynamic means grappling with a second question: How to match economic reform with political and social change? According to the 2009 Global Integrity Report, Arab countries, almost without exception, have some of the weakest anti-corruption systems in the world. Citizens have spent decades under martial law or emergency rule. Political parties and civil society groups are subject to repression and restriction. Judicial systems are far from free or independent. Elections, when they are held, are often rigged.

This leads to a third and often-overlooked question: Will the door to full citizenship and participation finally open to women and minorities? The first Arab Human Development Report in 2002 found that Arab women’s political and economic participation was the lowest in the world. Successive reports have shown little progress. The 2005 report called women’s empowerment – and I quote – a “prerequisite for an Arab renaissance, inseparably and causally linked to the fate of the Arab world.”

This is not a matter of the role of religion in women’s lives. Muslim women have long enjoyed greater rights and opportunities in places like Bangladesh and Indonesia. Or consider the family law in Morocco or the personal status code in Tunisia. Communities from Egypt to Jordan to Senegal are beginning to take on entrenched practices like child marriage, honor crimes and female cutting. All over the world we see living proof that Islam and women’s rights are compatible. Unfortunately, some are actually working to undermine this progress and export a virulently anti-woman ideology to other Muslim communities.

All of these challenges — from deep unemployment to widespread corruption to the lack of respect and opportunities for women – have fueled frustration among the region’s young people. And changing leaders won’t be enough to satisfy them. Not if cronyism and closed economies continue to choke off opportunity and participation. Or if citizens can’t rely on police and the courts to protect their rights. The region’s powerbrokers, inside and outside government, need to step up and work with the people to craft a positive vision for the future. Generals and imams, business leaders and bureaucrats, everyone who has benefited from and reinforced the status quo has a role to play. They also have a lot to lose if the vision vacuum is filled by extremists and rejectionists.

So a fourth crucial question is how Egypt and Tunisia should consolidate the progress that has been achieved in recent months.Former protesters are asking: How can we stay organized and involved? It will take forming political parties and advocacy coalitions. It will take focusing on working together to solve the big challenges. In Cairo last month, I met with young activists who were passionate about their principles but still sorting out how to be practical about their politics. One veteran Egyptian journalist and dissident, Hisham Kassim, expressed concerns this week that a reluctance to move from protests to politics would, in his words, “endanger the revolution’s gains.” He urged his young comrades to translate their passion into a positive agenda and political participation.

And as the people of Egypt and Tunisia embrace the full responsibilities of citizenship, we will look to transitional authorities to guarantee fundamental rights such as free assembly and expression, to provide basic security on the streets, and to be transparent and inclusive.

Unfortunately, this year we have seen violent attacks in Egypt and elsewhere that have killed dozens of religious and ethnic minorities, part of a troubling world-wide trend documented in the State Department’s annual human rights report released on Friday. Communities around the world, including my own, have struggled to strike the right balance between freedom of expression and tolerance of unpopular views. But each of us has a responsibility to defend the universal human rights of people of all faiths and creeds. And I want to applaud the Organization of the Islamic Conference for its leadership in securing the recent resolution by the UN Human Rights Council that takes a strong stand against discrimination and violence based upon religion or belief, but does not limit freedom of expression or worship.

In both Egypt and Tunisia, we have also seen troubling signs regarding the rights and opportunities of women. So far women have been excluded from key transitional decision-making processes. When women marched through Tahrir Square to celebrate International Women’s Day in their new democracy, they were met by harassment and abuse. You can’t claim to have a democracy if half the population is silenced.

We know from long experience that building a successful democracy is a never-ending task. More than 200 years after our own revolution, America is still working on it. Real change takes time, it takes hard work and patience – but it is possible. As one Egyptian women’s rights activist said recently, “We will have to fight for our rights… It will be tough, and require lobbying, but that’s what democracy is all about.”

We also know that democracy cannot be transplanted wholesale from one society to another. People have the right and responsibility to devise their own government. But there are universal rights that apply to everyone and universal values that undergird vibrant democracies everywhere.

And one lesson learned by transitions to democracy around the world is that it can be tempting to refight old battles rather than focus on ensuring justice and accountability in the future. I will always remember watching Nelson Mandela welcome three of his former jailors to his inauguration. He never looked back in anger, always forward in hope.

The United States is committed to standing with the people of Egypt and Tunisia as they work to build sustainable democracies that deliver real results for all their citizens, and to supporting the aspirations of people across the region. On this our values and interests converge. History has shown that democracies tend to be more stable, more peaceful, and ultimately, more prosperous. The trick is how we get there.

So this is a fifth question: How can America be an effective partner to the people of the region? How can we work together to build not just short-term stability, but long-term sustainability?

With this goal in mind, the Obama administration began to reorient U.S. foreign policy in the region and around the world from our first days in office. We put partnerships with people, not just governments, at the center of our efforts.

We start from the understanding that America’s core interests and values have not changed, including our commitment to promote human rights, resolve long-standing conflicts, counter Iran ’s threats and defeat al Qaida and its extremist allies. We believe those concerns are shared by the people of the region. And we will continue working closely with our trusted partners – including many in this room tonight — to advance these mutual interests.

We know that a one-sized fits all approach doesn’t make sense in such a diverse region at such a fluid time.

As I have said before, the United States has a decades-long friendship with Bahrain that we expect to continue long into the future. We have made clear that security alone cannot resolve the challenges facing Bahrain. Violence is not and cannot be the answer. A political process is. We have raised our concerns about the current measures directly with Bahraini officials and will continue to do so.The United States also strongly supports the Yemeni people in their quest for greater opportunity and their pursuit of political and economic reform that will fulfill their aspirations. President Saleh needs to resolve the political impasse with the opposition so that meaningful political change can take place in the near term in an orderly and peaceful manner.

And as President Obama has said, we strongly condemn the abhorrent violence committed against peaceful protesters by the Syrian government over the past few weeks. President Assad and the Syrian government must respect the universal rights of the Syrian people, who are rightly demanding the basic freedoms that they have been denied.

So going forward, the United States will be guided by careful consideration of all the circumstances on the ground and by our consistent values and interests.

Wherever we can, we will accelerate our work to develop stronger bonds with the people themselves – with civil society, business leaders, religious communities, women and minorities. We are rethinking the way we do business on the ground, with citizens themselves helping set the priorities. For example, as we invest in Egypt ’s new democracy and promote sustainable development, we are soliciting grant proposals from a much wider range of local organizations. We want to find new partners and invest in new ideas. And we are exploring ways to use connection technologies to expand our dialogue and open new lines of communication.

As we map out a strategy for supporting the transitions already under way, we know that the people of the region have not put their lives on the line just to vote in an election. They expect democracy to deliver jobs, sweep out corruption, and extend opportunities that will help them prosper and take full advantage of the global economy. So the United States will work with people and leaders across the region to create more open, dynamic, and diverse economies where all citizens can share in the prosperity.

In the short term, the United States will provide immediate economic assistance to help transitional democracies overcome their early challenges — including $150 million for Egypt alone.

In the medium term, as Egypt and Tunisia continue building their democracies, we will work with our partners to support an ambitious blueprint for sustainable growth, job creation, investment and trade. The U.S. Overseas Private Investment Corporation will provide up to $2 billion to encourage private sector investments across the Middle East and North Africa —especially for small and medium-sized enterprises. We are working with Congress to establish Enterprise funds for Egypt and Tunisia that will support competitive markets and provide small and medium-sized businesses with access to critical low-cost capital. Our Global Entrepreneurship Program is seeking out new partners and opportunities. And we are exploring other ideas, such as improving and expanding the Qualified Investment Zones, which allow Egyptian companies to send exports to the United States duty-free.

To spur private sector investment, we are working with Partners for a New Beginning, an organization led by former Secretary Madeleine Albright, Muhtar Kent of Coca-Cola and Walter Isaacson of the Aspen Institute. It was formed after the President’s Cairo speech and includes the CEOs of companies like Intel, Cisco, and Morgan Stanley. These leaders will convene a summit at the end of May to connect American investors with new partners in the region’s transitional democracies, with an eye toward creating jobs and boosting trade.

Under the auspices of Partners for a New Beginning, the U.S.-North Africa Partnership for Economic Opportunity is already building a network of public and private partners and programs that deepen economic integration among the countries in North Africa. This past December in Algiers, the Partnership convened more than 400 young entrepreneurs, business leaders, venture capitalists and Diaspora leaders from the United States and North Africa. These people-to-people contacts have helped lay the groundwork for cross-border initiatives to create jobs, train youth, and support start-ups.

For the long term, we are discussing ways to encourage closer economic integration across the region, with the United States and Europe, and around the world. The Middle East and North Africa are home to rich nations with excess capital and poorer countries hungry for investments. Forging deeper trade and economic relationships between neighbors could create new industries and new jobs. And across the Mediterranean, Europe also represents enormous potential for new economic partnerships and greater shared prosperity. Reducing trade barriers in North Africa alone could boost GDP levels by as much as 7 or 8 percent in countries such as Tunisia and Morocco, and could lead to hundreds of millions of dollars in new wealth across the region every year.

The people of the Middle East and North Africa have the talent and drive to build vibrant economies and sustainable democracies – just as citizens have done in other regions long held back by closed political and economic systems, from Southeast Asia to Eastern Europe to Latin America.

It won’t be easy. Iran provides a powerful cautionary tale for the transitions under way across the region. The democratic aspirations of 1979 were subverted by a new and brutal dictatorship. Iran’s leaders have consistently pursued policies of violence abroad and tyranny at home. In Tehran, security forces have beaten, detained, and in several recent cases killed peaceful protesters, even as Iran’s president has made a show of denouncing the violence against civilians in Libya and other places. And he is not alone in his hypocrisy. Al Qaida’s propagandists have tried to yoke the region’s peaceful popular movements to their murderous ideology. Their claims to speak for the dispossessed and downtrodden have never rung so hollow. Their arguments for violent change have never been so fully discredited.Last month we witnessed a development that stood out, even in this extraordinary season.

Colonel Qadhafi’s troops had turned their guns on civilians. His military jets and helicopter gunships had been unleashed upon people who had no means to defend themselves against assault from the air. Benghazi’s hundreds of thousands of citizens were in the crosshairs.

In the past, when confronted with such a crisis, all too often the leaders of the Middle East and North Africa have averted their eyes or closed ranks. But not this time. Not in this new era. The OIC and GCC issued strong statements. The Arab League convened in Cairo, in the midst of all the commotion of Egypt’s democratic transition. They condemned the violence and suspended Libya from their organization, even though Qadhafi held the League’s rotating presidency. They went on to call for a no-fly zone. I want to thank Qatar, the UAE and Jordan for contributing planes to help enforce it.

But that’s not all. The Arab League affirmed – and I quote – “the right of the Libyan people to fulfill their demands and build their own future and institutions in a democratic framework.”

That is a remarkable statement. This is reason to hope.

But all the signs of progress we have seen in recent months will only be meaningful if more leaders in more places move faster and further to embrace this spirit of reform… if they work with their people to answer the region’s most pressing challenges: How to diversify their economies, open their political systems, crackdown on corruption, and respect the rights of women and minorities.Those are the questions that will determine whether the people of the region make the most of this historic moment or fall back into stagnation.

The United States will be there as a partner, working for progress. We are committed to the future of this region and we believe in the potential of its people. And we look forward to the day when all the citizens of the Middle East and North Africa and around the world have the freedom to pursue their God-given potential.