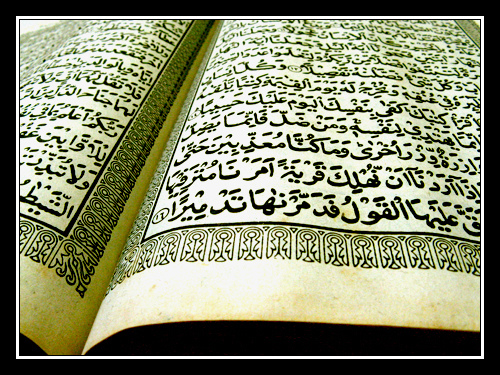

Fasting is the iconic act of piety in Ramadan, but for me the dominant association is actually the Qur’an. The fast is more of a background, passive act of faith. But reading the Qur’an, immersing yourself in its rhythm and poetry, is an active act. In my mind the singular image of Ramadan is not the lack of food but rather that of the muslim seated in the masjid and reading from the holy book.

There are two ways to read the Qur’an – as an act of devotion, or an act of inquiry. The former is to read the Qur’an in its original Arabic, which most muslims (myself included) do not speak or understand fluently. Qur’anic Arabic is a structured, formal language which is not actually used in modern Arabic societies, and it has its own very specific rules (called tarteel) that when followed in the recitation, result in an incredibly melodious and harmonic sound. These rules transcend just the mechanical sounds of the consonants and diacritical marks, and great qaris like Husari and Husain Saifuddin are masters of the art.

One might ask, what’s the point of reading the Qur’an in a language you don’t understand? The answer depends on belief. If you believe the Qur’an to be written by a man, then precisely none.

But if the Qur’an contains the literal Words of Allah as revealed, with

all divinity intact, then the mouth is repeating these divine words.

The eyes see the divine script, the ears hear the divine sound, of the

revelation.

It is said that from heaven, the angels perceive the reciter of the Qur’an as a shining star.

Further, the choice of the language of Arabic was no accident either. The

richness of Arabic poetry in the pre-Islam arabian culture had no

equal, and the Qur’an itself is a work of poetry on a scale that

completely overwhelmed the pagan worshippers. The power of Qur’anic

revelation was confirmation of the divine origin. This innate complexity

is intrinsic to the structure of the language itself:

As an act of inquiry, the Qur’an is read to plumb its infinite depths and attain religious insight. This is in many ways a dangerous intellectual challenge, because even for native Arabic speakers, the Qur’an is a dense and complex symbolic work. There are those who insist on a literal translation, of course, but it is generally agreed that the Qur’an requires some level of interpretation to be properly understood. For the native Arabic speaker, that interpretation may be personally derived, but for the rest of us, the Qur’an must be translated into our own native languages.

The very act of translation itself is a filter, that necessarily strips the Qur’an of its more complex symbolism, leaving only the superficial meanings intact. Skilled translators are able to evoke the sense of poetry of the original text, but there is inevitably some degradation, and the amount depends on the target language as much as the translator themselves. These are obstacles to understanding and inquiry, but not insurmountable ones. As long as these limitations are kept in mind, then there is still much to be gained from reading a translation, just as there is still a richness and diversity of life on the shoreline of the ocean. You aren’t sampling the depths, but the shallows still contain great wonders.

As far as translations to English go, three of the most common online are by Marmaduke Pickthall, Abdullah Yusufali1, and Mohammed Habib Shakir2. All three translations, along with Arabic script and additional commentary, can be viewed side-by-side for any range of ayats desired at the Digital Islamic Library Project‘s Multilingual Qur’an Online site, an indispensable tool. Of these three, I tend to use Yusufali’s The Meaning of the Holy Qur’an the most often, though there is a great discussion of other people’s choices at Talk Islam. Other translations that are highly recommended are Michael Sells’ Approaching the Qur’an: The Early Revelations and Muhammad Asad’s The Message of the Qur’an.

Given the diversity of translations, it’s hard to really recommend one. In fact the best course of action is to pick one, read it through, and then read another one immediately afterwards. Only by reading multiple translations can you really begin to build an appreciation for the complexity of the Qur’an’s message.

Speaking of which, I’ve spent my morning writing this post instead of reading my own Qur’an… time to go rectify that.

Photo credit: Bhiima on Flickr

[1] Yusufali’s biography is a fascinating and tragic read. His father was a Dawoodi Bohra from Surat, India and he was a devoted loyalist to the British Raj. Despite international acclaim for his translation, his life fell apart and he died alone and penniless in London in 1953.

[2] With respect to Shakir, there is some controversy about plagiarism from an earlier 1917 translation by Maulana Muhammad Ali.