Just in time for Lent, an unusual and dramatic exhibit of religious art has just opened at Washington’s National Gallery, and the Washington Post offers an assessment that, among other things, describes the lengths to which some artists will go for their work:

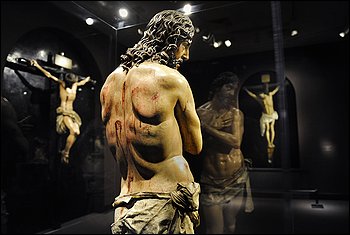

Before he started work on a religious piece, the Spanish sculptor Gregorio Fernández would pray, fast and repent for his sins — and practice some self-flagellation. When his statue of a naked, beaten Jesus was put up in a parish church around 1621, it was agreed that 15 masses would mention the artist’s name each year, forever, to cut his time in purgatory. Working on the piece, the artist made sure that every inch of it, even the parts in back no one might ever see, did an equally good job of capturing Christ’s bruised and bloodied skin. Fernández so cherished the reality and truth of Christ’s embodiment in flesh that he made his naked Jesus anatomically correct, even though he immediately hid that correctness, forever, under a glue-hardened loincloth.

Fernández must have believed in the worth of his art, as art. But it was the things his art pointed to that made it worth making at all. A sculpture could never grant you a parole from limbo; only the divinity it showed could do you that favor.

When we modern museum-goers admire a certain kind of old religious art for what it looks like, I think we get it wrong. Its look only helps it point to a reality beyond its surfaces, which counted as infinitely more important than the work of art itself.

“The Sacred Made Real: Spanish Painting and Sculpture, 1600-1700,” a groundbreaking exhibition that just touched down at the National Gallery of Art, should help us get back to this older and very different artistic understanding. If it does, this touring show, organized by curator Xavier Bray of the National Gallery in London, will turn out to have been one of the most substantial, important events our Washington museum has hosted. (In London, the show was a sleeper hit. Bray says they were expecting something like 25,000 aficionados. Instead they got four times that many visitors, including at one point “four punks and 50 nuns, intermingling.”)

Continue reading to find out why. And if you’re curious to see the exhibit for yourself, check out the National Gallery’s web site.