As I was looking over the readings for this weekend, I thought they sounded very familiar, and then it dawned on me: these were the same readings at my Mass of Thanksgiving, celebrated three years ago just after I was ordained.

As I approach the anniversary of my ordination, this reading from the Acts of the Apostles seems to have even more resonance. The account of the death of St. Stephen – the first martyr of the Church, and a deacon – reminds us of how this vocation began, with an extraordinary sacrifice. One man, giving his life for the gospel.

And remembering how it all began is to realize something humbling, and beautiful: to be a deacon of the church is to stand on the shoulders of giants. St. Stephen. St. Lawrence. St. Francis of Assisi. Deacons who left an enduring mark on our church.

This Sunday, deacons are preaching in every corner of the world – there are 17-thousand of them in the United States alone, from every walk of life. And the diaconate continues to grow at an astonishing rate. It is truly one of the great success stories of Vatican II. But there are still a lot of misconceptions about this ministry.

One of the most common is that permanent deacons are here because of the shortage of priests that started in the ’70s.

The real genesis came much earlier, during World War II, in the German concentration camp at Dachau.

During the Third Reich over 2,000 Catholic priests were held at Dachau. One out of every 25 deaths there, in fact, was a priest.

The priest prisoners were kept in cellblock 26, known as “Der Priesterblock.” For the imprisoned priests, this experience was transformative. While in Der Priesterblock, many of them began talking about how to renew the Church when the war was over. How could the Church better serve the world? One answer, they felt, would include bringing back an ancient order of service, the diaconate.

After the camp was liberated, the priests who survived returned to a Europe in ruins – a world desperately in need of evangelization, just as in the first century. Some of the priests formed what they called Deacon Circles of clergy and laity – circles of prayer, and service and charity. By the early 1960s, some of those priests from Dachau had become bishops. They attended the Second Vatican Council. And the rest, of course, is history.

And so it was that the modern diaconate took root and grew – from seeds watered with the blood of martyrs of the 20th century, the martyrs of Dachau.

It’s one more reminder that I stand on the shoulders of giants.

Just before I was ordained, I attended a retreat given by Deacon Bill Ditewig, who told an amazing story of the sacrifice men are making in our own day to become deacons, and serve the church.

In 2000, Bill attended a meeting in Rome where deacons from around the world gave presentations about their countries. Bill spoke about the thousands of deacons in the United States and how the vocation was thriving in this country. This was greeted with some polite applause. But a few minutes later, a deacon from Hungary got up to speak. He announced, with little fanfare, that his country had 46 deacons. And the room erupted into cheers.

Bill was taken aback. He figured there must be more to the story. He tracked down a translator and sought out the deacon from Hungary.

The Hungarian deacon explained that under communism, it was illegal to hold any religious assemblies, including classes for deacons. But in the early 1980s, there were nine men who wanted to try. Nine men who wanted to be deacons. What could they do? Well, behind the scenes, an arrangement was worked out. Every month, the men secretly – and illegally — crossed the border to Austria to study for a few days, and then come back. This went on for years. Back and forth, back and forth, risking arrest and even imprisonment. Finally, these nine men were ordained in Austria, to serve back home in Hungary. Once the Iron Curtain fell, the diaconate blossomed and grew.

And it happened, in large part, because of those nine men – each, risking everything for the gospel. Each in his way, a successor to Stephen, following in the footsteps of the first martyr.

Another reminder that I stand on the shoulders of giants.

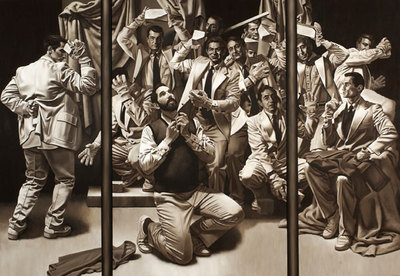

This church, of course, is dedicated to the Queen of Martyrs, and if you look around, you will see images and statues of them all over. But to your right, there is a rose window that has special significance. It depicts this moment from the Acts of the Apostles – the stoning of St. Stephen.

Every time I climb into this pulpit, I see him and am reminded of how this ministry began, and what I am here to do, to proclaim God’s word — the very act for which Stephen was killed.

And so it is that what started with St. Stephen has led us here: to this church dedicated to the Queen of Martyrs, the mother who holds in her heart all who have suffered and bled and died for what they believe.

Martyrs made our faith.

All of us who are here this day — all who hear the word of God, who worship within these walls and who welcome the sacrament we are about to receive — all of us are able to do this because of great men and women who came before us, and who gave their lives so that we could share in this banquet.

We are here because of them.

Let us pray that we always remember that.

Because, in one way or another, we all stand on the shoulders of giants.

[Anyone curious to learn more about the history and development of the diaconate should read Bill Ditewig’s definitive book on the subject, “The Emerging Diaconate.” A hard copy is available through Amazon or Paulist Press.]