In 1915, D.W. Griffith followed up his controversial silent classic “Birth of a Nation” with the ambitious epic “Intolerance,” which prominently featured a Catholic priest administering last rites to a condemned man.

Five years later, Bert Bracken would direct “The Confession,” about a priest bound by the seal of confession to keep secret information that could save an innocent man from the gallows. A similar plot device would be employed by Alfred Hitchcock in “I Confess” (1953), starring Montgomery Clift.

From Bing Crosby’s crooning curate in “Going My Way” (1944) to Karl Malden’s dockyard preacher in “On the Waterfront” (1954) to Max Von Sydow’s demon-battling Jesuit in “The Exorcist” (1973), men of the cloth have provided some memorable moments in the history of cinema. The same goes for foreign films. Just think of Don Pietro martyred by the Gestapo in Roberto Rossellini’s neorealist masterpiece “Open City” (1941).

What makes Catholic priests such compelling character studies?

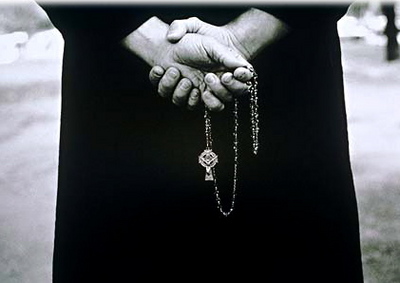

Perhaps part of it has to do with the nature of movies themselves. Film is an inherently visual art form, telling stories and conveying meaning through images rather than words. A Roman collar is one of those archetypal wardrobe pieces that communicate volumes before the character wearing it ever utters a line of dialogue.

Just as the cowboy hat signals grit, or the detective’s fedora hard-boiled toughness, so the priest’s collar serves as visual shorthand for morality, albeit at times flawed or distorted.

Or perhaps it has something to do with the priest’s traditionally understood role in society: that of intermediary between God and man.

“I think the vocation provides interesting and dramatic possibilities,” says Father Robert Lauder, a philosophy professor at St. John’s University in New York, who runs the popular Friday Film Festival at the Immaculate Conception Center in Douglaston, N.Y.

Check out the link for more.