“Do this in remembrance of me.”

There you have it: six words that changed the world.

They come to us from Paul’s letter to the Corinthians that we just heard – and they are the first known account that we have of the Last Supper. This description pre-dates even the gospels by a couple of decades, and offers our mandate and mission as Christians.

“Do this in remembrance of me.” And we do. And today at this altar, once again, we will.

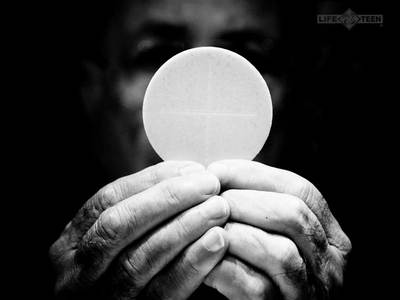

This lies at the heart of our lives as Catholics – this act of remembrance. Recalling and reliving this sacred moment, and cherishing what it means. What Christ offered us at the Last Supper – his body and blood – is his greatest tangible gift to the world. That is what we celebrate on this feast, Corpus Christi: the body and blood of Jesus Christ. A gift so overwhelming, and humbling. Here, the creator of everything becomes almost nothing: a slice of bread as thin as paper, to hold in our hands.

This feast is the last great Sunday celebration until November, when we mark the feast of Christ the King and prepare to begin Advent. This holy day, I think, is meant to nourish us through Ordinary Time the way the bread of life nourishes us – it is a kind of liturgical viaticum, food for the journey.

And like the miracle of the loaves and fishes we heard in Luke’s gospel, it is a miracle that extends beyond our wildest imaginings – feeding multitudes, even today. It satisfies every yearning, every hunger – the hunger for grace, for holiness, for God Himself. With the Eucharist, we get all that.

And what began at the table of the Last Supper in the hands of Christ continues today, at this table, in the hands of the priest. As this Year for Priests draws to a close, I want to share the story of a priest. Some of you may know his name: Walter Ciszek. There is a hall named for him up at Fordham. The cause of his canonization is being pursued and he has been declared a “Servant of God.”

Walter Ciszek was the son of Polish immigrants, born in a coal-mining town in Pennsylvania in 1904. He had a rough child hood – and was even a member in a gang. So his family was shocked when he announced that he wanted to become a priest. Young Walter ended up joining the Jesuits, and went to the Soviet Union to serve as a missionary. For a while, he worked as a logger, ministering to people privately, trying to avoid arrest.

Walter Ciszek was the son of Polish immigrants, born in a coal-mining town in Pennsylvania in 1904. He had a rough child hood – and was even a member in a gang. So his family was shocked when he announced that he wanted to become a priest. Young Walter ended up joining the Jesuits, and went to the Soviet Union to serve as a missionary. For a while, he worked as a logger, ministering to people privately, trying to avoid arrest.

But in 1941, he was arrested and charged, falsely, with working as a spy for the Vatican. He spent the next 23 years in prison – sometimes in solitary confinement, sometimes in a gulag, at times doing hard labor.

Despite that, he found ways to celebrate mass – often at tremendous risk. Years later, Fr. Ciszek wrote about it.

He described in painstaking detail how the prisoners would observe the Eucharistic fast, often going without breakfast, working all morning on an empty stomach, so they could receive communion. A priest would gather them in an assigned spot – everybody, even the priest, wearing rumpled work clothes. And there he would take a small piece of bread and a few drops of wine and transform them into the body and blood of Christ.

As he wrote: “In these primitive conditions, the Mass brought you closer to God than anyone might conceivably imagine. The realization of what was happening on the board, box, or stone used in the place of an altar penetrated deep into the soul.”

And he explained:

“Many a time, as I folded up the handkerchief on which the body of our Lord had lain, and dried the glass or tin cup used as a chalice, the feeling of having performed something tremendously valuable for the people of this Godless country was overpowering. I was occasionally overcome with emotion for a moment as I thought of how God had found a way to follow and to feed these lost and straying sheep in this most desolate land…I would go to any length, suffer any inconvenience, run any risk to make the bread of life available to these men.”

“Do this in remembrance of me.”

And so those words of Paul’s letter, Christ’s words to his followers, live on. In a Gulag in Siberia…or a chapel in Nigeria…or cathedral in Italy…or a neighborhood church, like this one, in the middle of Queens. The words live on, and the miracle continues. The multitudes continue to be fed. Grace abounds.

But do we understand what we have been given? Do we approach this sacrament with the humility and wonder of Walter Ciszek? When we gaze at the bread of life, do we realize we are gazing at God? Here is God in a form for which men like Fr. Ciszek and so many others suffered and sacrificed and even died.

This feast of Corpus Christi, this feast of remembrance, let us remember that. Every Sunday, we come forward for communion. But we cannot take this miracle for granted. And let us realize not only the tremendous gift we have been given, but also the generosity of the one who gave it. The words we pray just before communion, the words of the Centurian before Christ, speak for us all: “Lord I am not worthy.”

We aren’t. None of us is. And yet we pray to be made worthy, drawn to this sacrament by love, and by hunger. A hunger for the bread of life. A hunger to take God into our hands, and bring Him into our hearts.

And we are drawn as well by the desire to live out those six words that have changed the world – and that will change each of us, if only we let them.

“Do this in remembrance of me.”