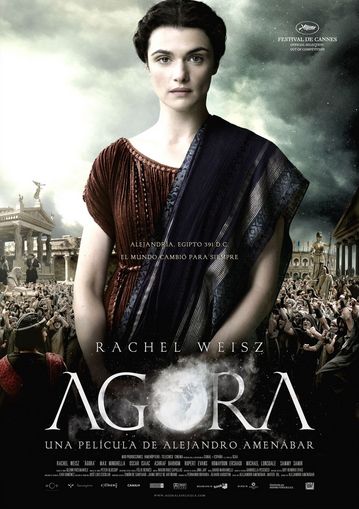

When I posted my recent essay on Synesius – the “bishop of dreams” and student of Hypatia -on this blog, I had no idea that writer-director Alejandro Amenábar had made a movie in Spain (“Agora”) with Rachel Weisz as Hypatia and Rupert Evans as her admiring student Synesius. Still less that it opened at the end of last week at a local arts cinema. That kind of nod from the universe can’t be ignored. I went to see the film today and here are some brief notes.

When I posted my recent essay on Synesius – the “bishop of dreams” and student of Hypatia -on this blog, I had no idea that writer-director Alejandro Amenábar had made a movie in Spain (“Agora”) with Rachel Weisz as Hypatia and Rupert Evans as her admiring student Synesius. Still less that it opened at the end of last week at a local arts cinema. That kind of nod from the universe can’t be ignored. I went to see the film today and here are some brief notes.

I enjoyed this film after I adjusted to the fact that Synesius is used as a fictional character. The historical Synesius was not a Christian in 391; he was not with Hypatia in the period before her murder; he was bishop of Ptolemais, not Cyrene (though that was his home city); and his attitudes to the new religion were not those of a convert but of a thoughtful and pragmatic man who saw the need to make an accommodation between the old and the new. However, for scripting purposes the continuity of the Synesius character, as one of Hypatia’s trio of student admirers who remain central to her drama, works well.

Clearly the writer-director wants us to see the resemblance between the Christian militants of this time and the Islamist fundamentalists of today, and he succeeds. Walk into a middle scene from this movie without any knowledge of context, and you might think you are looking at Taliban fanatics at play among the ruins of an ancient site – except that they are wearing crosses. Their contempt for women, and the rights of women, is identical.

The horrific martyrdom of a great woman philosopher and scientist at the hands of “Christian” thugs is in no way hyped in the movie; in the only two surviving accounts, Hypatia was actually skinned alive, an option considered by the mob leaders in the movie but not carried out by them.

The disparity of class and education between the Christians and the pagan establishment at this time is delineated very well, and we have no doubt that we are inside the agora of ancient Alexandria – and inside the Serapeum – as the action swirls between these locales.

The cast is excellent. Rachel Weisz is wonderful, pursuing her inquiries into the “crazy” theory that the Earth revolves around the sun in the midst of all the violence and religious hatred. The cinematography is sometimes breathtaking, especially when we are treated to aerial footage in which the book-burning Christian thugs are reduced to scuttling black beetles.

If you have ever heard Gibbon’s notorious pronouncement that the fall of Rome marked “the triumph of barbarism and of Christianity” (but have never read his Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire) this film will give you a few ideas about what he had in mind. The cameras take us there: to 391, when the remains of the great Library of Alexandria were all but destroyed, and to 415, when the greatest philosopher of her age was butchered. At the same time, the film speaks to us now, in our confused and divided world, about the cost of substituting religious authority and claims of exclusive revelation for rational inquiry and tolerance for the many paths to the sacred. This is an important movie with a timely agenda.