“I had a full-body orgasm last night,” reports a woman who divorced several years ago and has not dated since. “I thought I had given up sex, but in my dreams I’m with a series of fantastic lovers, doing it in all kinds of wonderful places, from a castle on a mountain to a tropical lagoon.”

“I had a full-body orgasm last night,” reports a woman who divorced several years ago and has not dated since. “I thought I had given up sex, but in my dreams I’m with a series of fantastic lovers, doing it in all kinds of wonderful places, from a castle on a mountain to a tropical lagoon.”

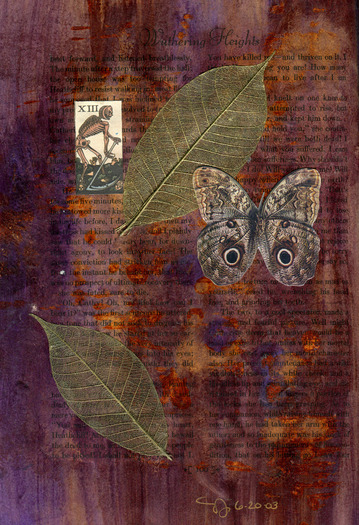

“I thought I had my life under control,” says an executive whose assistant schedules his days in five-minute blocks. “Then I discovered one night I own a jungle in the heart of Africa. It’w wild and dangerous, full of snakes and big cats. I’m scared to be there, and it’s way off the maps. Yet it’s kind of thrilling.”

When my life changed radically in the mid-1980s because of a series of dreams and visions that seemed to connect me to an ancient woman shaman, I walked away from commercial agendas and old definitions of success. I started living very modestly, following my calling as a dream teacher, for which there is no career track in our culture and for which financial returns are entirely unpredictable. I put aside whatever I once thought I knew about economics.

Then last weekend, in the midst of a spiritual conference in the Blue Ridge Mountains, I found myself in a group of Wall Street insiders who were discussing the fortunes of a famous American company. They had information that the company – and the price of its shares – were heading for a fall, and we proceeded to discuss which rival corporations might benefit from this. I woke with the feeling that I had been there, at that meeting, dressed for the part in the kind of pinstriped power suit I haven’t worn for decades.

These are all examples of an important dream function that Jung called compensation. A dream, he theorized, may attempt to compensate for “a hypertrophied conscious psychological tendency”. If we are overly rational in waking life, dreams may show us our wild side. If we are trying to lead celibate lives (as monks and nuns, famously, have discovered over the centuries) we may find ourselves in steamy sexual encounters, night after night, in the second life of dreaming. If (as in my case) we have tried to ignore or suppress the inner businessman, we may find him reasserting himself in our dream lives. In the Jungian approach, compensation works to help balance the four personality types that are active or dormant in each of us. Thus intellectual types dream of feeling situations, sensory types of intuitive breakthroughs. Similarly, introverts may get around and be highly gregarious in dreams, unafraid of wandering about naked in public.

The second life of dreams may take us beyond the mechanics of compensation into the experience of a parallel life, in which our second selves are leading a life we have been denied – or denied ourselves – in ordinary reality. Either way, such dreams may invite us to reach out and bring gifts and qualities from the second self into our everyday world, so we can be more whole and operate with more of ourselves.

When the stock market opened, I decided to act on the information that became available to my dream self up in the mountains over the weekend. Time will show whether it was reliable. Whatever the outcome, I’d rather bet on a dream than a calculation, and dreams may offer compensations in more senses than one.

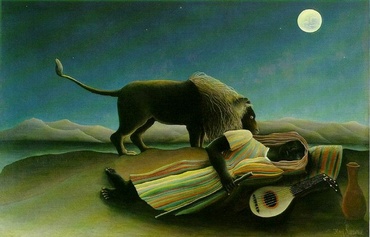

Sleeping Gypsy by Henri Rousseau (1897)