“How does one learn to tell stories which please kings?” – Fatima Mernissi, as a young girl.

“How does one learn to tell stories which please kings?” – Fatima Mernissi, as a young girl.

In Dreams of Trespass, a beautiful memoir of a harem girlhood in Morocco, Fatima Mernissi gives us a stunning example of how storytelling can facilitate soul healing. Her text is one that everyone – in the West and the East – knows something about. It is the collection of tales properly called A Thousand and One Nights. As Fatima explains what these stories meant to her, and what they mean for Muslim women in general, we become aware that in the West, we have almost no inkling of what they mean.

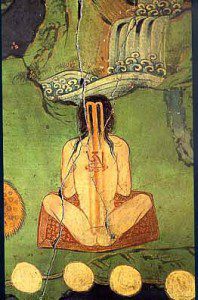

Scheherezade, the young bride of a savage tyrant who has killed her many predecessors, must spin a captivating tale every night to make the king postpone his plan to have her beheaded at dawn. Her husband, King Schariar, is possessed by the spirit of revenge. He discovered his first wife in bed with another man – a slave – and killing her was not enough to dissipate his raging hatred and distrust of women. He ordered his vizier to fetch, one by one, every virgin girl in the kingdom. He spent one night with each, then killed her. Now there are only two virgins left: the vizier’s own daughter, Scheherezade, and her little sister. Though her father wants her to escape, Scheherezade is willing to do her duty. She has a plan that will change everything.

As Fatima Mernissi tells it: “She would cure the troubled King’s soul simply by talking to him about things that had happened to others. She would take him to faraway lands to observe forign ways, so he could get closer to the strangeness within himself. She would help him to see his prison, his obsessive hatred of women. Scheherezade was sure that if she could bring the King to see himself, he would want to change and to love more.”

Scheherezade keeps the King spellbound through a thousand one nights, and at the end he is changed. He gives up his habit of murdering women.

Fatima first heard of Scheherezade from her mother, in the closed world of a harem in Fez. The word “harem” here does not mean a stable of concubines and slave girls, but a closed male-dominated world in which women of all ages are kept under lock and key, forced at every turning to think about the hudud, the boundary enforced by religion, law and custom. When little Fatima learns about Scheherezade, her first and eager questionto her mother is: “How does one learn to tell stories which please kings?”

This, of course, is the question we all need to answer, to heal our relationships – with ourselves as well as others – and our world.

Mernissi notes: “I was amazed to realize that for many Westerners, Scheherezade was considered a lovely but simple-minded entertainer, someone who relates innocuous tales and dresses fabulously. In our part of the world, Scheherezade is perceived as a courageous heroine and is one of our rare female mythological figures. Scheherezade is a strategist and a powerful thinker, who uses her psychological knowledge of human beings to get them to walk faster and leap higher. Like Saladin and Sindbad, she makes us bolder and more sure of ourselves and of our capacity to transform the world and its people.”

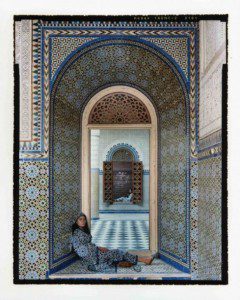

“Harem” by Lalla Essaydi from her stunning recent exhibition at the Edwynn Houk Gallery