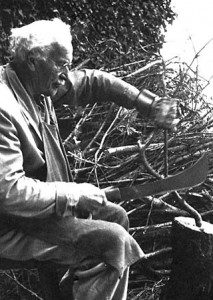

Happy Birthday to Carl Jung, who reminded us that psychology should be about soul, and that dreams are the easiest and best ways to understand what the soul wants in a life. In my book Dreaming the Soul Back Home, I call Jung “the dream shaman of Switzerland” and suggest that he is the very model of what a true shaman of the West might be.

Happy Birthday to Carl Jung, who reminded us that psychology should be about soul, and that dreams are the easiest and best ways to understand what the soul wants in a life. In my book Dreaming the Soul Back Home, I call Jung “the dream shaman of Switzerland” and suggest that he is the very model of what a true shaman of the West might be.

Despite the remarkable popularity of the beautiful recent edition of the Red Book – which Jung recorded in Gothic calligraphy from his personal journey through the Underworld – and the profusion of new editions and selections from Jung’s oeuvre you’ll find at almost any bookstore, not many people actually read and comprehend Jung’s own writings (as opposed to Jungian explications). His vast scholarship, including mastery of the classics, from which he sprinkles Greek and Latin throughout his monographs, is formidable and off-putting to many.

We start out with the simplicity of children. Then things get complicated, and we need to master a lot of experience and learning in order to get simple again.

Near the end of his life, Jung finally managed to put his best and most original ideas in a form that was simple enough to reach a general audience, without diluting or dumbing anything down. He might not have done this except for a dream.

After watching Jung’s very human interviews with John Freeman for the BBC in 1959, the publisher of Aldus Books had a bright idea: why not ask Jung to write a book for a general audience? Jung’s answer, when approached by Freeman, was a flat No. He was now in his 80s, and did not want to take the time that remained to him for this.

Then Jung dreamed that he was standing in a public place and lecturing to a multitude of people who were not only listening with rapt attention but understood what he was saying. The dream changed his mind.

Jung had said in Memories, Dreams, Reflections, “All day long I have exciting ideas and thoughts. But I take up in my work only those to which my dreams direct me.” Now he proved this, again, by embarking on the book that was published (after his death) as Man and His Symbols. He conceived it a collaborative effort and invited trusted colleagues like Marie-Louise von Franz to contribute chapters.

His personal contribution was a long essay titled “Approaching the Unconscious” . The essay is, first and last, about dreams. He completed it just ten days before the start of his final illness, so this work may be called his last testament. It testifies, above all, to the primary importance of dreams in Jung’s psychology and in his vision of human nature and evolution. Jung makes this ringing statement: “It is an age-old fact that God speaks, chiefly, through dreams and visions.”

The essay is as simple as Jung gets – which is to say, you must not be dismayed if you come across a word like “misoneism” (fear of the new) in the first few pages. Despite the hopes of his publishers and Jung’s dream on reaching the multitude, not nearly enough people – even in the Jungian community – are familiar with this essay, Second only to Memories, Dreams, Reflections, I recommend it as a friendly way into Jung’s work with dreams.

By the way, if you raise a toast to Jung today don’t assume that he won’t hear you. The first time I visited the Jung Center in Manhattan, where I recently gave a lecture on the development of Jung’s synchronicity theory, the male receptionist was in the midst of a phone call. “No,” he brought the conversation to an end. “I’m afraid Doctor Jung is not available for a private session. He died in 1961.” I ask whether the Center got many requests for private appointments with Jung. “At least three every week.” Given his own track record of talking to the dead, I suggested with a twinkle, maybe Jung might be available for a long-distance call.