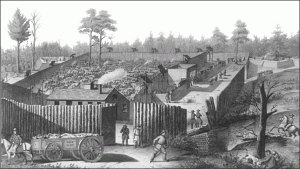

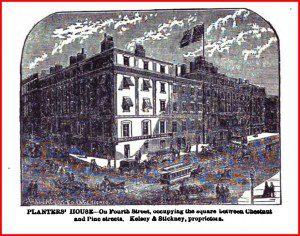

Inside a huge stockade hastily erected in Andersonville, Georgia, the Confederates operated the most notorious military prison of the American Civil War. In the last two years of the war, 13,000 Union soldiers died there from malnutrition, exposure and disease. One of the half-starved Union POWs who did not die was John McElroy of the Illinois 16th Cavalry. His prison letters suggest that his dreams sustained his will to live. Night after night, like the prisoner in Jack London’s Star Rover, he escaped from prison and traveled to much happier places. His favorite destination for these nocturnal journeys was the Planter’s House, a grand hotel filling a whole block on Fourth Street in St. Louis, where he had dined with his father when he was a young boy.

“One of the pleasant recollections of my pre-military life was a banquet at the Planter’s House, St. Louis, at which I was a boyish guest. It was, doubtless, an ordinary affair, as banquets go, but to me then, with all the keen appreciation of youth and first experience, it was a feast worthy of Lucullus.”

McElroy dreamed “hundreds of times” of revisiting the Planter’s House. In a typical visit, he sees the wide corridors with their “dancing mosaics”, enters the grand dining-room, and is escorted by “a dream friend to whose kindness I owed this wonderful favor,” into a room with mirrored walls, green ceilings, tables gleaming with cut-glass and silver, buffets with wines and fruits, and “a brigade of sleek, black, white-aproned waiters, headed by one who had presence enough for a major general.”

He was fed very well in the hotel restaurant, savoring all manner of “dainties” and dishes on the menu. All that he called for was supplied. Sometimes he sampled the whole menu, wanting to be able to say that he had tried all the dishes.

He was fed very well in the hotel restaurant, savoring all manner of “dainties” and dishes on the menu. All that he called for was supplied. Sometimes he sampled the whole menu, wanting to be able to say that he had tried all the dishes.

Awakening from these gourmet (and gourmand) dreams was of course a brutal disappointment. He returned to the prison to find himself “a half-naked, half-starved, vermin-eaten wretch, crouching in a hole in the ground, waiting for my keepers to fling me a chunk of corn bread.”

McElroy’s splendid dream dinners could be seen as compensation for the pain and hunger of his everyday existence as a POW. But they were more than escapism. His nightly relief from his daily circumstances helped him to survive. I would like to know more about that “dream friend” who took him to dinner.

Wanda Burch, author of She Who Dreams, discovered McElroy’s letters in the course of her current research for a book on the dreams of soldiers and their families during the American Civil War. Wanda will talk about her other discoveries and her current work in using Active Dreaming techniques to help heal veterans on my “Way of the Dreamer” radio show on October 9.