Last summer the Catholic bishop of Peoria, Daniel R. Jenky, called from the pulpit for “heroic Catholics” to oppose President Obama as the latest in a series of persecutors who “have tried to force Christians to huddle and hide only within the confines of their churches”. In the bishop’s version of history, the church survived “centuries of terrible persecution, during the days of the Roman Empire” and has been persecuted ever since, under Communism, Nazism and now (it seems) the Obama administration. Behind all of this? “The devil will always know their own, and will always hate us.”

In the midst of a U.S. presidential campaign, Bishop Jenky was repeating an old story: that Christians are soldiers in a perennial battle between good and evil that began in the first centuries after Christ and rages on more than 2,000 years later. We know that Christians, like members of other faiths, have sometimes suffered appalling punishment for standing by their beliefs. Many of us grew up on a Sunday school version of the first Christian martyrs being boiled in oil, fed to lions, stoned and bludgeoned, sautéed and flayed.

What if it wasn’t quite like that, in the Age of Martyrs during the three centuries between Jesus and Constantine? What if the story of the persecution and martyrdom of early Christians has been pumped up to grossly exaggerated proportions by pious propagandists with mixed agendas?

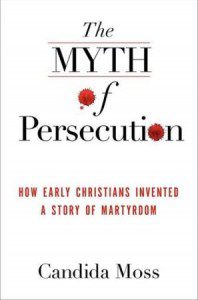

Candida Moss, professor of New Testament and Early Christianity at Notre Dame, lays out the evidence for thinking that the story of early Christian martyrdom has been exaggerated, and that we need to get the history right so that a myth of persecution does not continue to poison our public discourse. In her new book The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (HarperOne), Moss (the author of two previous scholarly works on martyrdom) combines the skills of a fine historical detective, a textual critic and an engaging writer. As she picks apart martyr narratives and draws from archaeology and Roman letters, we come to share her sense of the urgency of the task she has undertaken.

the story of early Christian martyrdom has been exaggerated, and that we need to get the history right so that a myth of persecution does not continue to poison our public discourse. In her new book The Myth of Persecution: How Early Christians Invented a Story of Martyrdom (HarperOne), Moss (the author of two previous scholarly works on martyrdom) combines the skills of a fine historical detective, a textual critic and an engaging writer. As she picks apart martyr narratives and draws from archaeology and Roman letters, we come to share her sense of the urgency of the task she has undertaken.

Moss argues that the general pattern of Roman action against Christians was not that of persecution, defined as an attack on a group because of its religious or racial identity, but rather prosecution, meaning action against people who broke the laws of the land. Many of the Christians who were killed by the Romans were prosecuted and executed for political reasons, not because they were Christians. The numbers who died are probably much lower than we may have thought. Christians weren’t liked by the Roman authorities, but prosecution was rare and persecution was limited to 10 or 12 years over the 300 years between Jesus and Constantine.

Already recognized as a leading authority on the martyrdom narratives, Moss devotes part of her new book to a careful but accessible inspection of the six martyr stories – only six out of hundreds – that were judged by the Society of Bollandists to be in any way “reliable”. Her conclusion? “All of the early Christian martyrdom stories have been altered…None of the early Christian martyrdom stories is completely historically accurate.” As she builds her case, she stirs us with personal flashes – of sitting in the amphitheater in Carthage, checking whether someone who wrote about the martyrdom of Perpetua could really have been close enough to see the whites of her eyes – and sharp-chiseled prose.

A classicist as well as a scholar of Christianity, Moss is especially interesting when she looks at the tradition of the “noble death” in the Greco-Roman world and how the authors of Christian martyr stories borrowed ideas and even plotlines from pagan literature and philosophy, including Greek romance novels.

She wants us to make the effort of imagination to approach the “Age of Martyrs” from a Roman perspective. The Romans were generally inclined to let subject peoples practice any religion they liked as long as they didn’t frighten the horses or disturb the “peace of the gods”. When a new territory was conquered, images of its gods were often set up in the Pantheon in Rome. Famously, the Romans imported the gods of the Greeks and hybridized them, giving them Roman names. Before the Christians arrived on the scene, the Romans had persecuted just two religious groups. They tried to annihilate the Druids, whom they saw as the heart of Celtic resistance to Roman rule, on the pretext that they practiced human sacrifice. And they outlawed the worship of Bacchus because the wild orgies of the bacchantes were seen as a threat to public order and the family.

Moss tracks the evolving Roman response to the spread of Christianity. She doubts that Nero (contrary to Tacitus) made Christians the scapegoats for the great fire of Rome, since he probably did not know who they are. She examines the fascinating correspondence between the emperor Trajan and Pliny circa 112, when Pliny was governor of Bithynia and Pontus in what is now Turkey. Pliny was concerned about the economic impact of “the contagion of this superstition” – the growing Christian movement. Attendance at the pagan temples had dropped off, so had sales of animals for sacrifice. Pliny reported that he had questioned some Christians under torture and thought it proper to execute a few who refused to abjure their faith because they deserved to be punished for “obstinacy and stubbornness”. The emperor agreed, but also counseled that they did not want to “seek out” Christians.

In edgy times, the Balkan-born emperor Decius, installed by his army, decreed that everyone must make sacrifice to the genius of the emperor. This edict, issued in 250, was a challenge to Christians but did not target them specifically. In 258, Valerian issued a savage and specifically anti-Christian edict, ordering the immediate execution of Christian deacons, priests and bishops and the seizure of property of wealthy Christians, to be followed by their execution if they refused to curse Christ and honor the imperial cult. Valerian’s son withdrew these decrees two years later, and Christians seem to have been tolerated – though disliked – under the empire until the great persecution initiated by Diocletian in 303. Moss describes this as “the first and only period of persecution that fits with popularly held conceptions about persecution in the early church.” One of Diocletian’s edicts required everyone (man, woman, child) to gather in public places to sacrifice, on pain of execution. We can be thankful that he did not have modern tools for enforcement.

Moss follows the trail of the early martyrs after Constantine, into a period of internecine conflict within the church, when Donatists (who had refused to yield anything to Rome during the persecution) warred with “Catholics” like Augustine in north Africa. The Donatist camp spawned a fierce group of violent killers, called Circumcellions (“From the places – cella – of the maryrs”), who attacked and murdered peaceful merchants on the roads and invaded churches, stabbing and clubbing worshippers to death. Some of these people were would-be martyrs in an uncomfortably contemporary sense. They killed enemies of their version of a faith while hoping that by dying in their fight they would be ushered into a place of heavenly rewards by martyrs who had gone before them. An uncomfortable window into an aspect of early Christian martyrdom that is little-known, but seems chillingly relevant to our times.

Moss returns, with informed passion, to her central thesis. The belief in a persecuted and therefore morally righteous church continues to distort and inflame public debate, encouraging an us-versus-them mentality that makes dialogue impossible because it demonizes those of differing opinions. If you think you belong to a persecuted community, that may lead you to think it is okay – even essential to survival – to attack others. As Moss argues, the rhetoric of persecution legitimates retributive violence, depicting it as divinely approved self-defense.

With ringing clarity, Moss offers a choice to her Christian readers:“Christians can choose to embrace the virtues of the martyrs without embracing the false history of persecution that has grown up around them.” The Myth of Persecution is essential reading for everyone who wants to understand the true history of Christianity and of violence in the name of religion.

Full disclosure: Candida Moss is my daughter. I have listened to cogent, well-reasoned versions of religious history from her since she was nine, when she delivered an impromptu one-hour lecture on the Buddha from the back of the car. I am very proud of her.

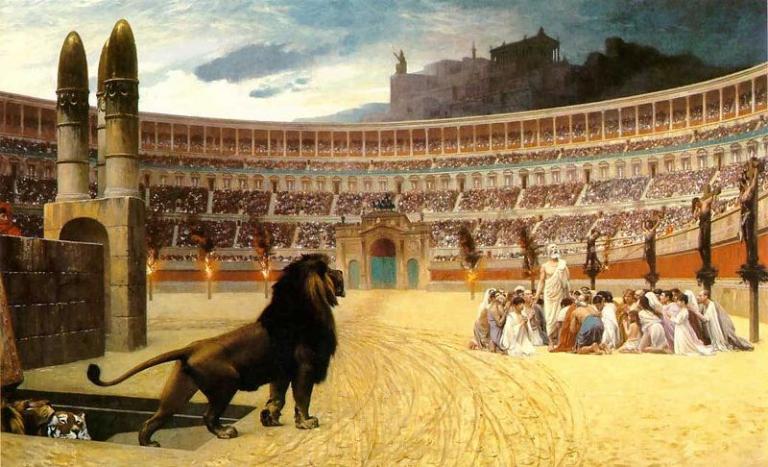

Image: The painting titled “The Christian Martyrs’ Last Prayer” by French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme “, commissioned by William T. Walters in 1863 and delivered twenty years later, conforms to countless legends about early Christians and lions. The problems with the painting reflect the problems with the Christian martyr stories. The artist, widely known for his realism and fidelity to historical detail, told his patron that he had depicted martyrs in the Circus Maximus. But the seating arrangements are those of the Colosseum, and the hill with the statue in the background resembles the setting of the Acropolis in Athens more than the hills of Rome.