The founding fathers had a dream of a new society. Many of them also paid close attention to dreams of the night. On July 4, it seems appropriate to share the story of how two of them shared dreams over many years. One of those dreams warned of the folly of trying to enforce Prohibition. Another appears to have contained long-range precognition of the deaths of the second and third president of the United States, on July 4, 1826.

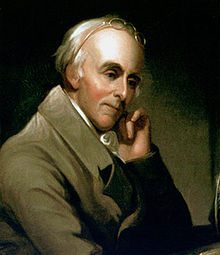

The friendship between Dr Benjamin Rush of Philadelphia and John Adams, the second president of the United States, is a grand example of what it means to travel through life with a true companion of mind and spirit. They were together in the Continental Congress; both of them signed the Declaration of Independence; their imaginations helped to forge a new political order; they both weathered political storms and bitter adversity. This was also a great epistolary friendship. Adams and Rush corresponded with extraordinary intimacy and liveliness; the doctor’s wife said they wrote to each other “like two young girls about their sweethearts”

As a doctor and pioneer psychiatrist, Rush recorded the dreams of his patients and used them in diagnosis. Since his first travels to Europe before the American Revolution, he had been keenly interested in precognitive dreams. He developed a lifelong habit of journaling his own dreams.

During visits to the Massachusetts home of John and Abigail Adams, Rush learned that Adams also took a keen interest in dreams. Rush suggested that they should exchange dreams and Adams agreed to match Rush “dream for dream.” They proceeded to swap dreams in a way that was – and is – quite unusual for white men of power and influence in America.

Adams shared a political dream that dramatized the difficulty of creating a civilized democratic system in France. In his dream, he was in front of the palace of Versailles, trying to explain the requirements of democracy to an immense crowd of wild beasts. He was howled down and in danger of being ripped apart.

Rush reported a dream in which he became president and used his power to bring in prohibition. This resulted in a storm of protest, and finally a visit from a wise old man who counseled him that “the empire of habit” is stronger than “the empire of reason” and must be respected. This dream was another corrective to the doctor’s waking assumptions. Having observed the effects of alcoholism – and having been reared in a stern Presbyterian faith – he was an early supporter or prohibition, until this dream.

Adams and Rush inspected each other’s dreams for guidance on many other issues, both political and personal, including the opposition to Adams’ efforts to create an American navy.

The most remarkable letter in the Adams-Rush correspondence was signed by Benjamin Rush on October 16, 1809. At this point, John Adams and Thomas Jefferson, once close allies and friends, had been estranged because of political disagreements for eleven years. Rush described a dream in which his son read him a page from a history of the United States. “I read it with great pleasure and send you a copy of it.”

The page from the supposed dream history described “the renewal of the friendship and intercourse between Mr. John Adams and Mr. Jefferson, two ex-Presidents of the United States.” This led to “a correspondence of several years in which they mutually reviewed the scenes of business in which they had been engaged”, producing valuable lessons for posterity. “Many precious aphorisms, the result of observation, experience and profound reflection, it is said, are contained in these letters.” The dream history added: “These gentlemen sunk into the grave nearly at the same time”, outliving their adversaries.

We may suspect that in writing this page, Dr. Rush was attempting a dream transfer rather than simply forwarding a dream report, using that form to press for reconciliation between the two former presidents. The following week, Adams sent him a pleasant response: “A dream again! I wish you would dream all day and all night, for one of your dreams puts me in spirits for a month.” He then proceeded to make it brusquely clear that he was not ready for reconciliation, stating that (despite eleven years on non-communication) “there has never been the smallest interruption of the personal friendship between me and Mr. Jefferson” and adding, with a haughtiness that was not his usual style, that “Jefferson was but a boy to me” and that he “taught him everything that has been good and solid in his whole political conduct.”

Rush’s dream intervention did not bring Adams and Jefferson together right away. “Of what use can it be for Jefferson and me to exchange letters?” Adams rebuffed Rush’s continued efforts to play peacemaker on Christmas Day, 1811. “I have nothing to say to him, but to wish him an easy journey to heaven.” Yet just one week later, on New Year’s Day, 1812, John Adams penned a careful overture to Jefferson, and the two ex-presidents moved quickly and gratefully to full reconciliation. The correspondence between them over the following years is an extraordinary gift to our understanding of the birth of democracy in America. Fourteen years later, they “sunk into the grave”, outliving most of their enemies, on the same day.

“This is the Fourth of July”, Thomas Jefferson announced on his deathbed at Monticello on the evening of July 3, 1826. Informed that the day of celebration had not yet arrived, he drifted back to sleep. When he died at one o’clock in the afternoon on July 4th, bells could be heard ringing in Charlottesville in the valley below.

A few hours later, lying on his own deathbed in Quincy, Massachusetts, with a thunderstorm raging outside, John Adams whispered, “Thomas Jefferson survives.” Then his heart stopped. Whether the page from Dr Rush’s future history was dream or imagination, its prophecies were exactly fulfilled.

–

For a full account of the dreams of the Founding Fathers, please see my book The Secret History of Dreaming, where the sources for the facts and quotations in this article are provided.

For a full account of the dreams of the Founding Fathers, please see my book The Secret History of Dreaming, where the sources for the facts and quotations in this article are provided.