Most human societies have valued dreams and the dreamers for three principal reasons. They have recognized that in dreams we see the future, and this can help whole communities as well as individuals to make better choices. They have understood that dreams give us a direct line to the sacred, to the God/Goddess we can talk to, to the ancestors, to the animate spirits of Nature. And they have grasped that dreaming can be very good medicine. Dreams diagnose problems before they present symptoms; they offer imagery for self-healing; and they show us the state of the soul and can help us retrieve parts of our vital energy that may have gone missing through what shamans call “soul-loss”.

Most human societies have valued dreams and the dreamers for three principal reasons. They have recognized that in dreams we see the future, and this can help whole communities as well as individuals to make better choices. They have understood that dreams give us a direct line to the sacred, to the God/Goddess we can talk to, to the ancestors, to the animate spirits of Nature. And they have grasped that dreaming can be very good medicine. Dreams diagnose problems before they present symptoms; they offer imagery for self-healing; and they show us the state of the soul and can help us retrieve parts of our vital energy that may have gone missing through what shamans call “soul-loss”.

In Western society, dreams are undervalued by those the English call the “talking classes”, especially in academe and the media. Yet we all dream, so this is common property. Ever the hardhead who says “I don’t dream” is only saying “I don’t remember” or “I don’t care to remember”. And when life is tough or he is going through a big life transition, his head may be cracked open by a big dream that will expand his understanding and maybe give him sources and resources not otherwise available. One of the most common types of “big dreams” that can accomplish that is a visitation by a dead family member or loved one.

All ancient and indigenous peoples that I have encountered, in my studies as an independent scholar and in my travels, understand that the dream world is a real world, maybe more real than the regular world of our consensual everyday hallucinations. When I told an elder of the Longhouse People, or Iroquois, about my dreams of the Mohawk “woman of power”, he told me “you made some visits and you received some visitations.” There you have a central understanding, forgotten or ignored in much of Western psychology: dreaming is traveling. In dreams, soul or consciousness gets around, far beyond the body. In dreams, we may also receive visitations. The very words for “dream” in many cultures reflects this insight. In the language of the Makiritare, a shamanic dreaming people of Venezuela, the word for “dream” is adekato, which literally means “a journey of the soul.”

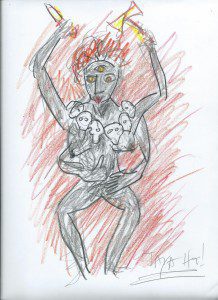

Look at what is painted on the walls of the Paleolithic caves and you have evidence of the central importance of dreaming from as far back in the human odyssey as we can trace. The images are portals into a deeper reality, not simply hunting or fertility magic, but ways of connecting with the spirits, of calling through power, and of traveling between dimensions. On the most practical level, dreaming has always been a key part of our human survival kit. When we were little better than naked apes, without good weapons, dreaming helped save us from becoming breakfast for leathery raptors or saber-toothed tigers, by enabling us to scan our environment, across space and time, and identify possible dangers.

We want to learn to meld ways of dreaming and healing that our ancestors knew with the best of science and scholarship today. The methods of Active Dreaming that I teach and practice are not a “New Age” approach, but the revival of ancient wisdom, adapted to our contemporary lives, and providing essential tools to get us through life’s challenges and find and fulfill our bigger and braver stories.

–

For more on the importance of dreaming throughout human history and evolution, please see my book The Secret History of Dreaming.

“Cave Shaman” drawing (c) Robert Moss