Nobody knows for sure when Jesus was born, but it is rather unlikely that it was on December 25th. The famous early bishop, Clement of Alexandria, who died in 215, wrote that many Christians in his day believed that Jesus was born in April. December 25 was only recognized as the birthday of Jesus by the Church in Rome in the mid-fourth century, and it took centuries for the date to be adopted by Christian congregations elsewhere. The church in Jerusalem only adopted the date in the 7th century. It took England a century longer.

On the other hand, the significance of December 25 in the pagan calendar had long been established. Under The Julian calendar, instituted by command of Julius Caesar in 45 BCE, December 25 was made the date of Bruma, the “shortest” day, meaning the winter solstice. Early European peoples honored the winter solstice as the day of the re-birth of the sun, personified as a god by some, a goddess by others.

In 274, the soldier-emperor Aurelian proclaimed that December 25 was the birthday of Sol Invictus, the Unconquered Sun. This was a composite deity he hoped would be acceptable to believers of all persuasions, including the old worshippers of Helios-Apollo and the Roman legionaries who had adopted the cult of Mithras, a god from the East whose birth from a cave was already celebrated on December 25. So the day we now celebrate as Christmas became Dies Natalis Solis Invicti, the Day of the Unconquered Son.

Against this backdrop, it seems more likely than not that intelligent leaders of the early Church were inspired to move Jesus’ birthday to December 25 to claim the glamor of the old winter solstice festivals and to match the religious calendar to the celestial calendar in the way that early peoples had always done, making the coming of the Christos coincide with the re-birth of the sun. This, at any rate, was the opinion of a learned Syriac scholiast, Jacob Bar-Salibi, who wrote in the 12th century:

It was a custom of the pagans to celebrate on the same 25 December the birthday of the sun, at which they kindled lights in token of festivity. In these solemnities and revelries the Christians also took part. Accordingly when the doctors of the Church perceived that the Christians had a leaning to this festival, they took counsel and resolved that the true Nativity should be solemnized on that

day.

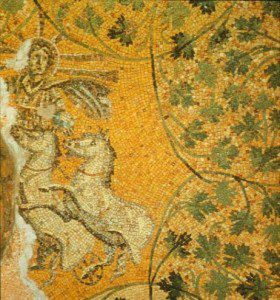

Syncretism – the bringing together of different strands of belief and custom – was characteristic of the old Roman religions; in the mid-4th century, when the Christian leaders chose to make December 25 the birthday of Jesus, it became an act of Church policy. In a ceiling mosaic in the tomb of the Julii, in the necropolis under St Peter’s, we have an arresting visual image of the convergence of the old solar cult with the new religion. It shows the figure of Sol-Helios, the sun god, riding his chariot. Around 250, his image was touched up, to make the rays around his head resemble a cross.

When we look at the customs and symbols of Christmas that are most loved in our families today, we find that many of them are of pagan origin: the Christmas tree, for starters, but also the holy and the ivy, the mistletoe, the yule log, the giving of gifts, the reindeer that fly through the sky. An early Christian grinch in Britain, Polydor Virgil, thundered that “dancing, masques, mummeries, stageplays, and other such Christmas disorders now in use with Christians, were derived from these Roman Saturnalian and Bacchanalian festivals; which should cause all pious Christians eternally to abominate them.”

The happy news is that the grinches will never win (though I’m not so sure about the retailers). The sun returns, and at Christmas all peoples of good heart will share gifts of light and love.