Let’s be candid: Jung’s Red Book is not for the faint-hearted. Yes, there are passages of incandescent beauty, perhaps beyond any other of his writings. There are also vertiginous falls into places of rank terror and screaming madness. In my own reading, there was a moment when I wanted to throw the book violently across the room – and may well have done so, except that the book is the size and weight of a tombstone, and I feared for breakages.

Let’s be candid: Jung’s Red Book is not for the faint-hearted. Yes, there are passages of incandescent beauty, perhaps beyond any other of his writings. There are also vertiginous falls into places of rank terror and screaming madness. In my own reading, there was a moment when I wanted to throw the book violently across the room – and may well have done so, except that the book is the size and weight of a tombstone, and I feared for breakages.

The moment when I was close to chucking the book came when Jung describes how he found himself compelled (by a woman he identified as his soul!) to eat part of the liver of a murdered girl. I was revulsed, almost gagging. And I forced myself to read on, to go every step with Jung on his frightful shamanic journey through the many cycles of the Netherworld.

Let’s be even more clear: Jung goes through hell. He converses with a Red Devil. He battles with a Bull God and shrinks him to the size of an egg he can fit in his pocket, then raises up the old horned god again. He howls to a dead moon and a dark sea about combining good and evil, but he doesn’t trust his own shouting.

He comes to a library that may be a place of sanctuary and reflection. When the librarian asks him to choose the book that he wants, to their mutual surprise he names The Imitation of Christ by Thomas à Kempis, a medieval favorite. He debates with the librarian what it would mean to imitate Christ today. He decides that since Christ imitated no one, this would mean going his own way, and paying the full price for creating that way that no one before him has mapped or trodden.

He finds himself in a kitchen attached to the library, conversing with a plump, matronly cook. There’s a great stir in the air and a host of the restless dead come flying through, yelling about going to Jerusalem. He demands why these dead are not at rest, and their leader tells him that he must explain that to them. He tells the dead that they can’t rest because of what they failed to do in their lives. The dead clutch at him, and he shouts, “Let go, daimon, you did not live your animal” – by which he means the instinctive, natural life of the senses.

The noise of this altercation is so loud the police come and carry him away to a madhouse where a little fat professor diagnoses “religious madness” after the briefest of interviews. “You see, my dear, nowadays the imitation of Christ leads to the madhouse.”

He is confined in a room between two other patients, one sunk in lethargy, the other with a fast-shrinking brain. He compares himself to Christ crucified between two thieves, one of whom will go up, the other down. His mind turns on the problem of dealing with the dead, which the kitchen scene taught him is vaster than he had known – “the dead who have fluttered through the air and lived like bats under our roofs from time immemorial.” This will require “hidden and strange work”, but it is not clear how he can do this from his confinement.

He listens to a voice praising madness, a voice he identifies as his soul. “Madness is a special form of the spirit and clings to all teachings and philosophies, but even more to daily life, since life itself is illogical.”

In the night, everything heaves in his room in black billows. The walls become terrible waves. He finds himself now in the smoking room of a great ocean liner, where the professor reappears in beautiful clothes and offers him a drink, while telling him he is utterly mad and must be committed. The torpid neighbor from his room reappears and announces he is Nietzsche, and also the Savior. Back in his locked room at the madhouse, he struggles with entangling webs of words and ideas. He cannot tell whether it is day or night when he hears a roaring wind and then sees a great wall of darkness advancing on him.

He opens his eyes and looks up into the jolly round face of the cook. “You’re a sound sleeper,” she tells him. “You’ve slept for more than an hour.” Jung thinks he is awake, but of course he is still in a dream, and far from his physical home.

Once again, we see the price Jung paid for his knowledge of the depths. He commented in his Epilogue to the Red Book, nearly half a century later, that he would certainly have gone mad “had I not been able to absorb the overpowering force of the original experiences.”

Some of the processes he developed in that heroic effort are ones that are suitable for all of us. He wrote his way through, by journaling and then writing up his journals. He sought and created images of balance and integration, which became a fascinating series of mandalas. And he developed the approach he called active imagination, by which – instead of rejecting the characters and contents of dream and fantasy – we work with them, carrying the drama forward towards healing and resolution. This is the shaman’s way, attuned to our modern language of understanding, but born in the depths of primal experience.

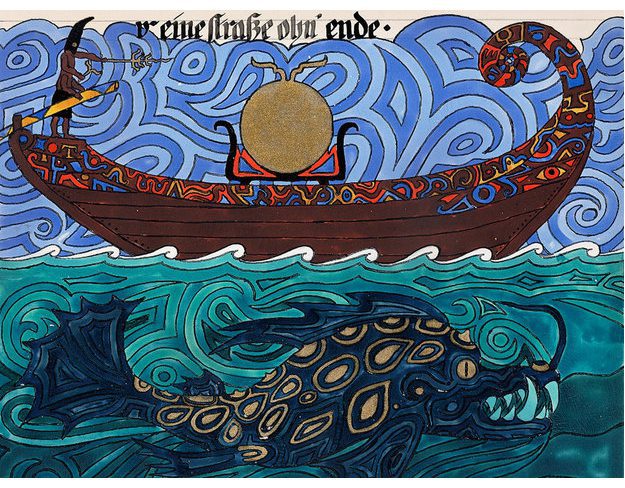

Illustration from Jung’s Red Book.