Early fathers of the Christian church were in favor of active dreaming and astral travel. Tertullian, who famously observed that “most people derive their knowledge of God from dreams” urged Christians who found themselves in captivity, perhaps on the way to martyrdom, to get out and about in their astral bodies:

Though the body is shut in, though the flesh is confined, all things are open to the spirit. In spirit, then, roam abroad; in spirit walk about, not setting before you shady paths or long colonnades, but the way which leads to God. As often as in spirit your footsteps are there, so often you will not be in bonds. The leg does not feel the chain when the mind is in the heavens. [Tertullian, Ad Maryras, 197 CE]

Athanasius explained in Contra Gentes that “when the body is still, at rest and sleeping, a man is in inner movement – he contemplates what is outside himself, he traverses foreign lands, he meets friends and often through them [dreams] he divines and learns in advance his daily actions. What else could this be [that travels] but a rational soul [psyche logike]?”

St. Augustine described travels of the “phantom” who can visit another person in dreams.

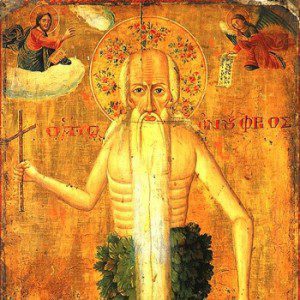

John of Lycopolis (d. 394), one of the Desert Fathers, became famous for his ability to travel in his dream body. A saint of the Coptic church, John was well-known during his life as a hermit for his austerities; he lived in a cave and ate only fruit consumed after sundown. He was believed to have great psychic gifts. Emperors and generals consulted him, as a seer, on the outcome of future battles and political conflicts. He was attributed “mighty works” of healing and prophecy.

He was fully aware of the ways in which psychic energy can work outside – and on – the physical body, and of the reality of dream travel and dream visitations.

John was about ninety when a Roman tribune implored him to see his wife. She was anxious about a possibly dangerous journey by river and wanted the holy man’s blessing. John had not seen a woman in forty years, and refused to see this one. The tribune’s wife was persistent, swearing that she would not embark on her journey without John’s blessing. When the tribune reported this to John, the desert father said, “I shall appear tonight to her in a dream, and then she must not still be determined to see my face in the flesh.” The tribune reported this to his wife.

That night, John came to her in a dream. He told her modestly, “I am a sinful man and of like passions with you.” He added “Nevertheless I have prayed for you and for your husband’s household, that you may walk in peace according to your faith.” The tribune’s wife woke up and related the dream to her husband, who confirmed John’s appearance as she had perceived him. She sent her husband to thank him, convinced she had received a real blessing.

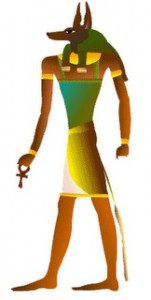

It is significant that this account of a dream visitation by an early Christian father involves a former cult center of one of the Egyptian deities most closely associated with astral travel. In Greek, Lycopolis means “City of the Wolf”. The “wolf” in question is the jackal- (or dog-) headed god Wepwawet, whose name means “Opener of the Ways”.

Wepwawet is similar to Anubis in both attributes and functions. Both are divine gatekeepers and psychomps – soul-guides – for both the living and the dead. In early times, Wepwawet was a god of Upper (or southern) Egypt while Anubis was worshipped in Lower (or northern) Egypt; later, they became syncretized. Special to Wepwawet is the function of serving as a scout and bodyguard for the pharaoh and his generals. His image appears on the shedshed, the battle standard of Upper Egypt, and he is often depicted in battle gear carrying a mace and a bow. So it is interesting that John of Lycopolis was valued by generals as a battle seer and is said to have provided accurate forecasts of the outcome of the Emperor Theodosius’ struggles with opposing armies and rebels.

The primary source on John of Lycopolis and his dream visitation is The History of the Monks of Egypt, an anonymous account of a journey by a group of seven brothers from a monastery on the Mount of Olives to the desert fathers in Egypt in the 380s. The author does not expound on the past history of Lycopolis, whose former residents included the great experiential philosopher Plotinus as well as a jackal-headed god. But the world of the Monks of Egypt is a magical landscape where ascetic superheroes work miracles, do battle with evil spirits – and operate on the astral as well as the physical plane. The desert holy men live in a separate reality. “Some of them do not even know that another world exists on earth or that evil is found in cities.” Yet “it is clear to all who dwell there that through them, the world is kept in being.”