The young Charles Darwin developed a passion for collecting and classifying beetles, that deepened when he was able to tramp around the wet Welsh shore during a soggy vacation, aged ten. He was a boarder at a school (Shrewsbury) where nothing like science was taught – Latin and Greek grammar, learned by rote, were supposed to instill the mental discipline to get an English gentleman through anything – so Darwin learned on his own, with the help of some curious family and friends. When his headmaster learned that he had set up a home chemistry lab with his elder brother Erasmus, he hauled him in front of the school as a study in “stupidity”, wasting his mind “on gases and suchlike rubbish”.

The young Charles Darwin developed a passion for collecting and classifying beetles, that deepened when he was able to tramp around the wet Welsh shore during a soggy vacation, aged ten. He was a boarder at a school (Shrewsbury) where nothing like science was taught – Latin and Greek grammar, learned by rote, were supposed to instill the mental discipline to get an English gentleman through anything – so Darwin learned on his own, with the help of some curious family and friends. When his headmaster learned that he had set up a home chemistry lab with his elder brother Erasmus, he hauled him in front of the school as a study in “stupidity”, wasting his mind “on gases and suchlike rubbish”.Habits of curiosity, developed in childhood – with or without encouragement or support – lay a foundation and a direction for later creative work.

Recollecting my own childhood, these habits and passions included:

Making pictures

We did not have TV in my boyhood homes until I was on the edge of puberty. So I made pictures on my own mental screen, listening to a creepy midnight radio show called “Inner Sanctum” (it began with a creaking door) seeing scenes in the fireplace, entertaining the after-images from the books I read late into the night, and from my dreams.

Making dramas

I loved to stage performances, mostly with historical or mythic themes. When I could recruit my peers, we did this with dress-up stuff, hats and capes and wooden or plastic swords and weapons. I staged more complex dramas – sometimes miniature versions of War and Peace – with toy soldiers on the floor of my room. I created complex dioramas, with rivers and forests and towns and rairoads. As I moved figures around, I sometimes felt I was directing or redirecting a drama that was being played out in another time or a world within the world on the regular scale, These “little wars” and “little worlds” came fully alive in my dream life, where I was able to miniaturize myself and enter the scenes, with the players fully alive around me.

Practicing poetic and eidetic memory

I collected scratched LPs of poets reading their poetry – T.S. Eliot and Yeats were my favorites. With the help of these, and by walking about for hours and hours reciting from their books, I memorized a huge quantity of their verse when I was very young. And of course I wrote lots of poetry myself. I think I was growing the habit of bardic memory. With my visual games – looking at a picture or landscape, then calling it up behid closed eyelids – and my constant hunt for resemblances (seeing a face in tree bark or an animal in a rock) I laid a foundation for eidetic memory.

Bibliomania

We are going to “read like horses”, Charles Darwing’s elder brother promised him when he was sent to join Erasmus Darwin at Edinburgh university. Well, I read – and still do – like one of Mark Twain’s bicycle-mounted knights. I rode my bike on Canberra weekends to every church, school, or library fete where used books were on sale, hard-pedaling home with my wire basket sagging to the mudguard of the front wheel. I discovered Aldous Huxley, D.H.Lawrence, Konrad Lorenz, Frank Yerby’s steamy tales of plantation life – and how many more – in this way. And would stay up reading in bed, contrary to all regulations and suggestions, until 4 am on school mornings, to be dragged out of bed, to get on my bike and ride to school..

Shifting consciousness

Because I was in acute and fairly constant pain from the age of 3 (when I first “died” in a hospital, from double pneumonia) until 11 (when I emerged from the shadow of life-threatening illness) I became habituated to shifting my consciousness beyond the body and its travails. I not only mastered pain, so I never require medication or anesthetics for that; I became habituated to traveling in realms beyond the physical, through simple intention.

To release our full creative powers, we want to work and play with the child inside us who is the master of imagination, and we bring that child most alive when we indulge the habits and passions that he or she loves. I’m looking now at the toys on my desk – model soldiers, bears of all sizes, a tiger pencil sharpener, a world inside a marble.

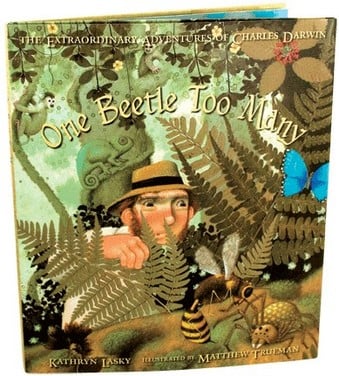

Matthew Trueman’s illustrations for One Beetle Too Many bring Darwin’s enthusiasms richly alive. I