It’s a saying of the Kagwahiv, an Amazonian dreaming people: “Everyone who dreams is a little bit shaman.” Or, in an alternate translation: “Everyone who dreams has a little bit of the shaman in them.” I remember vividly when I first heard this quoted by an anthropologist who had lived with the Kagwahiv, when I attended a conference of the Association for the Study of Dreams in Santa Fe, back in 1993.

It’s a saying of the Kagwahiv, an Amazonian dreaming people: “Everyone who dreams is a little bit shaman.” Or, in an alternate translation: “Everyone who dreams has a little bit of the shaman in them.” I remember vividly when I first heard this quoted by an anthropologist who had lived with the Kagwahiv, when I attended a conference of the Association for the Study of Dreams in Santa Fe, back in 1993.

The Kagwahiv are right. It is no less correct to flip and amplify the statement, as follows: Every shaman is a big-time dreamer.” Or: Every shaman dreams big.

We have been enjoying a resurgence of shamanic practice in Western society. This is partly due to the work of teachers like Michael Harner (who made the important contribution of stripped-down “core” techniques for shamanic journeying) and the wonderful Sandra Ingerman (who has brought us a clean and clear approach to soul retrieval as a mode of healing). It is also connected to our hunger for experiential knowledge of ancestral traditions such as those evoked by Joseph Campbell and the great “archeomythologist” Marija Gimbutas.

In all the descriptions of the shaman in the literature – as wounded healer, as guide of souls, as walker between worlds, as negotiator with the spirits – there is an essential element that is rarely featured strongly enough, and is sometimes missed altogether. First and last, the shaman is a dreamer. Shamans typically receive their calling in dreams, and are initiated and trained in the Dreamtime. The heart of their practice is the intentional dream journey. They may incubate dreams to diagnose for a patient and to select the appropriate treatment. They travel – wide awake and lucid – in their dream bodies to find lost souls, to intercede with the spirits, to fight sorcerers and to guide spirits of the departed along the right roads.

Yes, hallucinogens or “entheogens” are characteristic of shamanic traditions in some parts of the world, especially South America. But the master shamans manufacture their own chemicals inside their bodies, and hallucinogens are never required for a truly powerful dreamer. They have never been part of my own practice, but then I was called by dreams in early boyhood, and discovered the reality of other worlds during life-threatening illnesses, so I do not judge those who seek help in opening the strong eye of vision.

In the language of the Mohawk (who have never used hallucinogens as part of shamanic practice) the shaman is “one who dreams (atetshents), a term that also means “doctor” and “healer”.

In the languages of other indigenous peoples, especially in Native America, the connection between dreaming and shamanic practice and perspectives is equally clear. For the Makiritare of Venezuela, a dream is an adekato, a “journey of the soul”. Among the Dene (Athabascans), the same words are used to designate dreams, visions and shamanic journeys. Among the Wind River Shoshone, the word navujieip means both “soul” and “dream”; the navujieip “comes alive when your body rests and comes in any form.”

Among the Aborigines of Walcott Inlet, it is believed that the high god Unggud summons potential shamans in dreams. Their initiation will depend on their ability to brave up to a series of fearsome tests, at the end of which they are reborn with a new body and a new brain filled with light. The shaman now has the ability to project a dream double. His powers are described as miriru. In Aboriginal Men of High Degree, A.P.Elkin explains that miriru is fundamentally “the capacity bestowed on a medicine man to go into a dream state or trance with its possibilities.” Here, built into the language of the Earth’s oldest people, is the understanding that the heart of the shaman’s power lies in his or her ability to dream.

In our everyday modern lives, we stand at the edge of such power, when we dream and remember to do something with our dreams.

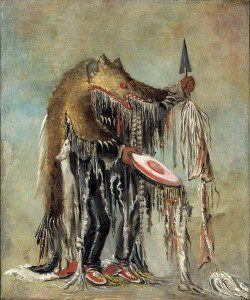

Bear shaman of the Nez Perce by George Catlin