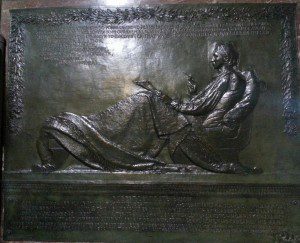

I am currently in Edinburgh, the birth city of Robert Louis Stevenson, and often feel as I roam the town that haunted his imagination – even after he moved to Bournemouth, or traveled the world, or settled in his last home in Samoa – that I am walking in his steps. I admire his habit of keeping a notebook with him at all time for his observations and ramblings. He once called this his Book of Original Nonsense. I resonate with his delight in travel, despite his frail health (his trip to America in 1879, featuring awful train journeys, nearly killed him) and his opinion that “to travel hopefully is better than to arrive.” I love his passion for Scottish history, and am inspired by his willingness to tackle the theme of the double and to plumb the depths of light and dark in the human psyche.

I am currently in Edinburgh, the birth city of Robert Louis Stevenson, and often feel as I roam the town that haunted his imagination – even after he moved to Bournemouth, or traveled the world, or settled in his last home in Samoa – that I am walking in his steps. I admire his habit of keeping a notebook with him at all time for his observations and ramblings. He once called this his Book of Original Nonsense. I resonate with his delight in travel, despite his frail health (his trip to America in 1879, featuring awful train journeys, nearly killed him) and his opinion that “to travel hopefully is better than to arrive.” I love his passion for Scottish history, and am inspired by his willingness to tackle the theme of the double and to plumb the depths of light and dark in the human psyche.

I have long inspired by his practice as a writer dreaming. He said that dreams unfold in “that small theater of the brain which we keep brightly lighted all night long.” He stated that The Strange Case of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, radically original in its time, was “conceived, written, re-written, re-re-written, and printed inside ten weeks” in 1886. The conception came in a dream:

“For two days I went about racking my brains for a plot of any sort; and on the second night I dreamed the scene at the window, and a scene afterward split in two, in which Hyde, pursued for some crime, took the powder and underwent the change in the presence of his pursuers.”

His wife related how one night RLS cried out in his sleep, horror-stricken. When she shook him awake, he protested,quite properly, “Why did you waken me? I was dreaming a fine bogy-tale!” He appeared the next morning rhapsodizing, “I have got my shilling-shocker — I have got my shilling-shocker!”

RLS wrote about how dreams fed his writing throughout his life. During his boyhood, his dreams were so vivid and moving that they were more entertaining to him personally than any literature. He learned early in his life that he could dream complete stories and that he could go back to the same dreams on succeeding nights to give them a different ending. Later he trained himself to remember his dreams and to dream plots for his books.

He described the central role of dreaming and dreamlike states in his creative process in “A Chapter on Dreams”. During his sickly childhood, he was often oppressed by night terrors and the “night hag”. But as he grew older, he found that his dreams often became welcome adventures, in which he would travel to far-off places or engage in costume dramas among the Jacobites.

He often read stories in his dreams, and as he developed the ambition to become a writer, it dawned on him that a clever way to get his material would be to transcribe what he was reading in his sleep. When he lay down to prepare himself for sleep, he “no longer sought amusement, but printable and profitable tale” (a very Scottish approach to the creative endeavor). His dream producers accommodated him. He noticed they became especially industrious when he was under a tight deadline. When “the bank begins to send letters” his “sleepless Brownies” worked overtime, turning out marketable stories.

In his “Chapter on Dreams” (written in his house on Saranac Lake in upstate New York and published in Across the Plains) RLS gave a vivid depiction of his dream helpers.

“Who are the Little People? They are near connections of the dreamer’s, beyond doubt; they share in his financial worries and have an eye to the bank-book; they share plainly in his training; they have plainly learned like him to build the scheme of a considerate story and to arrange emotion in progressive order; only I think they have more talent; and one thing is beyond doubt, they can tell him a story piece by piece, like a serial, and keep him all the while in ignorance of where they aim…

“And for the Little People, what shall I say they are but just my Brownies, God bless them! who do one-half my work for me while I am fast asleep, and in all human likelihood, do the rest for me as well, when I am wide awake and fondly suppose I do it for myself. That part which is done while I am sleeping is the Brownies’ part beyond contention; but that which is done when I am up and about is by no means necessarily mine, since all goes to show the Brownies have a hand in it even then.”

He observed that “my Brownies are somewhat fantastic, like their stories hot and hot, full of passion and the picturesque, alive with animating incident; and they have no prejudice against the supernatural.” – and have no morals at all.”

For more on writers dreaming, please see my Secret History of Dreaming.