“Father, Son and Holy Ghost,” said the burly man who approached me after one of my lectures. “That’s it. I was raised Irish Catholic, and there’s no need for dreams in my religion.”

I did not argue, but remarked gently that he might want to look at the role of dreams in the Bible, and in the early church.

I had a similar exchange with a Protestant fundamentalist on a plane, a seemingly mild and thoughtful woman with whom I enjoyed a pleasant conversation until I asked if she remembered her dreams. She immediately froze. “I don’t dream,” she said, gritting her teeth. “I’m a Christian.”

Ironic, because on the evidence of both scripture and history, it can be said that there might be no Christianity without dreams and visions, and that it was a vision followed by a dream that made Christianity the religion of the West.

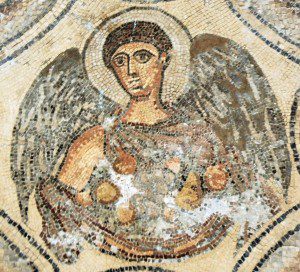

Through dreams and visions, according to the Bible, Mary and Joseph learned the identity of the extraordinary being who was coming to join the family. Without a visitation from the archangel of dreams, Joseph might have believed the rumors that Mary had had sex with another man (the favorite suspect being a Roman soldier called Pantera) and cast her out, giving the world a different story.

The vision of a star guided the Magi toBethlehem, and their dreams persuaded them not to return to Herod with the location of the wonder child, enabling the holy family to escape into Egypt and thus saving the life of baby Jesus.

A no less famous vision, on the road to Tarsus, turned a Jewish tax collector who was hostile to the Jesus cult into a passionate and effective proselytizer for the new faith. Saul (who now became Paul) was caught up into the “third heaven” and could not say whether he was “in the body or out of it.”

Three days after his execution, the vision of Jesus, radiantly alive at the place of his burial, provided evidence of his promise of life beyond death. Only the women could see him at first. Then the sight and senses of the men were opened.

The interlocking dreams and visions of the Roman centurion Cornelius and of the apostle Peter turned a Jewish sect into a world religion. A dream inspired Cornelius to send for Peter and offer to join the Christians. In the moment that Cornelius was reaching to him, a vision persuaded Peter to make the gentile welcome. A vision of a banquet of non-kosher food convinced Peter that non-Jews should be permitted to become Christians.

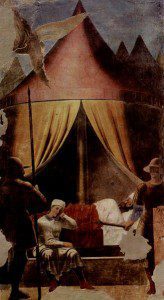

Three centuries later, the vision of a Roman emperor, unfolded in a dream, made Christianity the religion of the West.

Constantine had his vision in 312, on the eve of battle with the army of Maxentius, his rival for the throne. As church historian Eusebius told it, claiming the Emperor as his direct source, Constantine was feeling the need for divine support as his enemies in Rome mounted psychic attacks and offered blood sacrifices to the old gods to bring about his defeat.

Constantine prayed to the supreme deity to reveal himself and “stretch forth his hand”. On their march,Constantine and “all the troops” saw a “sign of the cross” in the noonday sky, inscribed with the words, “By this, conquer.”Constantine went to bed wondering what the sign meant. That night he was visited by a numinous being bearing the same symbol who ordered him to “use its likeness in his engagements with the enemy.”

Constantine ordered the manufacture of the sign he has been given, as a standard with the Greek letters “chi-ro” at the top of a cross. Under the new sign, Constantine’s army routed Maxentius’s forces on the banks of theTiber. Maxentius drowned in the river near the Milvian bridge.

It is possible that Christian intent – through focused prayer and even the group practice of dream-sending – generated the Emperor’s visionary experiences. Certainly such things were believed possible at the time. Commenting on the effects of focused group intention, the early church father Origen suggested that “if the Romans ever pray with complete agreement, they will be able to subdue many more pursuing armies than were destroyed by the power of Moses.”

It was a Roman proverb that “the proof of a god is best found in his protection”. The lord of battles believed by Constantineto have given him a sign and then a victory became the Lord of the Roman Empire.

Scholars are divided over how Constantine viewed and understood his God. He delayed Christian baptism until he was on his deathbed. Some historians suggest that he was vague about the distinction between the Christian God and Helios, the old sun-god, though in Pagans and Christians Robin Lane Fox maintains that Constantine personally worked up a sermon delivered on Good Friday in 324.

Either way, the vision and the dream of an Emperor transformed the West into Christendom.

adapted from The Secret History of Dreaming by Robert Moss. Published by New World Library.