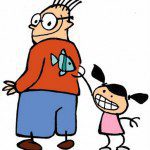

In many parts of Europe, an April Fools prank is called an “April fish”. The term poisson d’Avril first broke surface in a French poem in the early 1500s. The oirginal, smelliest, version of such a prank was to attach a dead fish to the back of an unsuspecting victim, and let him slowly become aware – if he missed the sniggers of those around him – by the odor. In kinder times, a paper cut-out fish was substituted. The person who was fooled was himself called an “April fish”, meaning that he was a young fish who was easily caught.

In many parts of Europe, an April Fools prank is called an “April fish”. The term poisson d’Avril first broke surface in a French poem in the early 1500s. The oirginal, smelliest, version of such a prank was to attach a dead fish to the back of an unsuspecting victim, and let him slowly become aware – if he missed the sniggers of those around him – by the odor. In kinder times, a paper cut-out fish was substituted. The person who was fooled was himself called an “April fish”, meaning that he was a young fish who was easily caught.

This was a folk custom very familiar to Carl Jung, and it played into his understanding of symbols and synchronicity.

When Jung was immersed in his study of the symbolism of the fish in Christianity, alchemy and world mythology, the theme started leaping at him in everyday life. On April 1, 1949, he made some notes about an ancient inscription describing a man whose bottom half was a fish. At lunch that day, he was served fish. In the conversation, there was talk of the custom of making an “April fish” – a European term for “April fool” – of someone. In the afternoon, a former patient of Jung’s, whom he had not seen for months, arrived at his house and displayed him some “impressive” pictures of fish. That evening, Jung was shown embroidery that featured fishy sea monsters. The next day, another former patient he had not seen in a decade recounted a dream in which a large fish swam towards her.

Several months later, mulling over this sequence as an example of the phenomenon he dubbed synchronicity, Jung walked by the lake near his house, returning to the same spot several times. The last time he repeated this loop, he found a fish a foot long lying on top of the sea-wall. Jung had seen no one else on the lake shore that morning. While the fish might have been dropped by a bird, its appearance seemed to him quite magical, part of a “run of chance” in which more than “chance” seemed to be at play.

If we’re keeping count (as Jung did) this sequence includes six discrete instances of meaningful coincidence, five of them bobbing up, like koi in a pond, within 24 hours, and all reflecting Jung’s preoccupation with the symbolism of the fish. Such unlikely riffs of coincidence prompted Jung to ask whether it is possible that the physical world mirrors psychic processes “as continuously as the psyche perceives the physical world.”