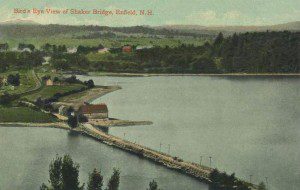

Bertha Huse, a teenage mill girl, goes out for a walk in the cool morning mist of a New Hampshire fall. This is her habit, but her family worries when she does not return for breakfast and does not show up for work. A few hours later, a full-scale search is in progress. She likes to walk a Shaker bridge across Lake Mascoma, and it is feared she may have fallen into the water and drowned. The mill owner sends for a diver. There is no sign of Bertha above or below water.

Bertha Huse, a teenage mill girl, goes out for a walk in the cool morning mist of a New Hampshire fall. This is her habit, but her family worries when she does not return for breakfast and does not show up for work. A few hours later, a full-scale search is in progress. She likes to walk a Shaker bridge across Lake Mascoma, and it is feared she may have fallen into the water and drowned. The mill owner sends for a diver. There is no sign of Bertha above or below water.

In another New Hampshire village, five miles away, Nellie Titus has been following reports of the search and grieves for the family. A couple of nights later, she screams in her sleep and her husband shakes her awake. She rebukes him for waking her before she had seen where the missing girl was. She tells him firmly that he must never interrupt her sleep, whatever she seems to be doing.

A reputation for dreaming true runs in Nellie’s family. Her grandmother had the gift. It is not clear whether Nellie is dreaming of the missing girl or dreaming as her. On another night, she makes it her focused intention to solve the mystery. She emerges from the new dream complaining that she is “oh so cold.” It seems she has joined the girl in the lake, in the place of her drowned body. Nellie is certain she knows exactly where the body is located.

She persuades her husband to get out the buggy and drive to the Shaker bridge. She makes him stop half-way across, gets out and to the edge. She points down at the dark water around the bridge supports. “She is there.”

They go to George Whitney, the manager of the mill where Bertha work, and insist he should get a diver to search again, under the bridge. Whitney is a decent master, but he is also a man of reason and science – these are the 1890s, after all! But the village has been stricken by Bertha’s disappearance, and he agrees to give it a try. The diver, a wiry, skeptical Irishman named Brian Sullivan, is reluctant to go down. But when Nellie gives an exact account of where the body is located, jammed in the structure of the bridge, with a leg protruding, it is agreed that one dive will be made, at the place she points out.

That is exactly where Bertha’s body is found. It was invisible to the diver, as he groped underwater. Almost certainly, he would have missed it, except that he had received exact directions from a psychic dreamer in contact with the spirit, or at least the situation, of the dead girl.

The case attracted tremendous public interest, and led William James, the towering pioneer of both psychology and psychic research in the United States, to lead a full investigation. James’ wrote a report, based on extensive interviews, in 1898 for the American Society of Psychical Research, titled “A Case of Clairvoyance”.* Sullivan, the diver, said that he was far less scared of a cadaver in the water than of the psychic “woman on the bridge” who knew just where the body was to be found. William James used his the case of Nellie Titus in his campaign to link science to spirit, and build a body of evidence to crack open the closed minds of those he called “orthodoxers”. He declared that the case of the woman on the bridge was “a decidedly solid document in favor of the admission of a supernormal faculty of seership.”

Shaker bridge, Enfield N.H., 1908. Public domain.